1.13 Worth noting: global vs. local variables

As we knew before that Global Variables that the OS zeros them automatically unlike Local Variables

Sometimes, you have a global variable and forgot (initialize) and your program depends on it being zero from the beginning. After that you modify the program and move this global variable inside a function to make it local. Then it won't be zeroed during initialization again, and this can bring annoying Bugs

1.14 Accessing passed arguments

The author started saying that we understood that the function that calls another function sends the parameters through the stack. But how does the called function (callee) access these parameters?

A simple example:

#include <stdio.h>

int f (int a, int b, int c) { // defines function f that takes three integers and returns an integer

return a * b + c; // returns the result of a multiplied by b plus c

}

int main() { // program entry point; defines the main function

printf("%d\\n", f(1, 2, 3)); // calls printf to print the result of f(1,2,3) followed by a newline

return 0; // returns success; indicates successful execution

}

1.14.1 x86

MSVC

Here this is what we see after the Compilation (MSVC 2010 Express):

_TEXT SEGMENT ; starts the text segment for code

_a$ = 8 ; size = 4 ; defines offset for parameter a (8 bytes from EBP)

_b$ = 12 ; size = 4 ; defines offset for parameter b (12 bytes from EBP)

_c$ = 16 ; size = 4 ; defines offset for parameter c (16 bytes from EBP)

_f PROC ; starts the procedure for function f

push ebp ; pushes EBP onto the stack to save the previous base pointer

mov ebp, esp ; sets EBP to current ESP, establishing the stack frame

mov eax, DWORD PTR _a$[ebp] ; moves the value of a (at [EBP+8]) into EAX

imul eax, DWORD PTR _b$[ebp] ; multiplies EAX by the value of b (at [EBP+12]) and stores in EAX

add eax, DWORD PTR _c$[ebp] ; adds the value of c (at [EBP+16]) to EAX

pop ebp ; pops the saved EBP to restore the previous stack frame

ret 0 ; returns from the function, with 0 bytes to clean up (callee cleans)

_f ENDP ; ends the procedure for f

main PROC ; starts the procedure for main

push ebp ; pushes EBP onto the stack

mov ebp, esp ; sets EBP to ESP

push 3 ; third parameter ; pushes 3 onto the stack as third argument

push 2 ; second parameter ; pushes 2 onto the stack as second argument

push 1 ; first parameter ; pushes 1 onto the stack as first argument

call _f ; calls function f

add esp, 12 ; cleans up 12 bytes from the stack (3 arguments * 4 bytes)

push eax ; pushes the return value from f (in EAX) onto the stack for printf

push OFFSET $SG2463 ; '%d', 0aH, 00H ; pushes the address of the format string for printf

call _printf ; calls printf

add esp, 8 ; cleans up 8 bytes from the stack (2 arguments * 4 bytes)

; return 0 ; comment for returning 0

xor eax, eax ; sets EAX to 0 using XOR (faster than mov eax, 0)

pop ebp ; restores EBP

ret 0 ; returns from main

_main ENDP ; ends the main procedure

What we see here is that main() pushes 3 numbers onto the stack and calls f(int, int, int).

Accessing the parameters inside f() is done using macros like: _a$ = 8, in the same way we handle local variables but with positive offsets (addresses are determined by addition).

Meaning here, we point to the outer stack frame by adding the macro _a$ to the value in register EBP.

After that, the value of A is stored in register EAX. After executing IMUL instructions, the value in EAX will be the result of multiplying the value in it with the content of _b.

Then, using ADD we add the value of _c to EAX.

The value in EAX doesn't need to be moved, it's in the place it needs to be.

And upon returning to the caller, the value in EAX goes in the next call as a parameter to printf().

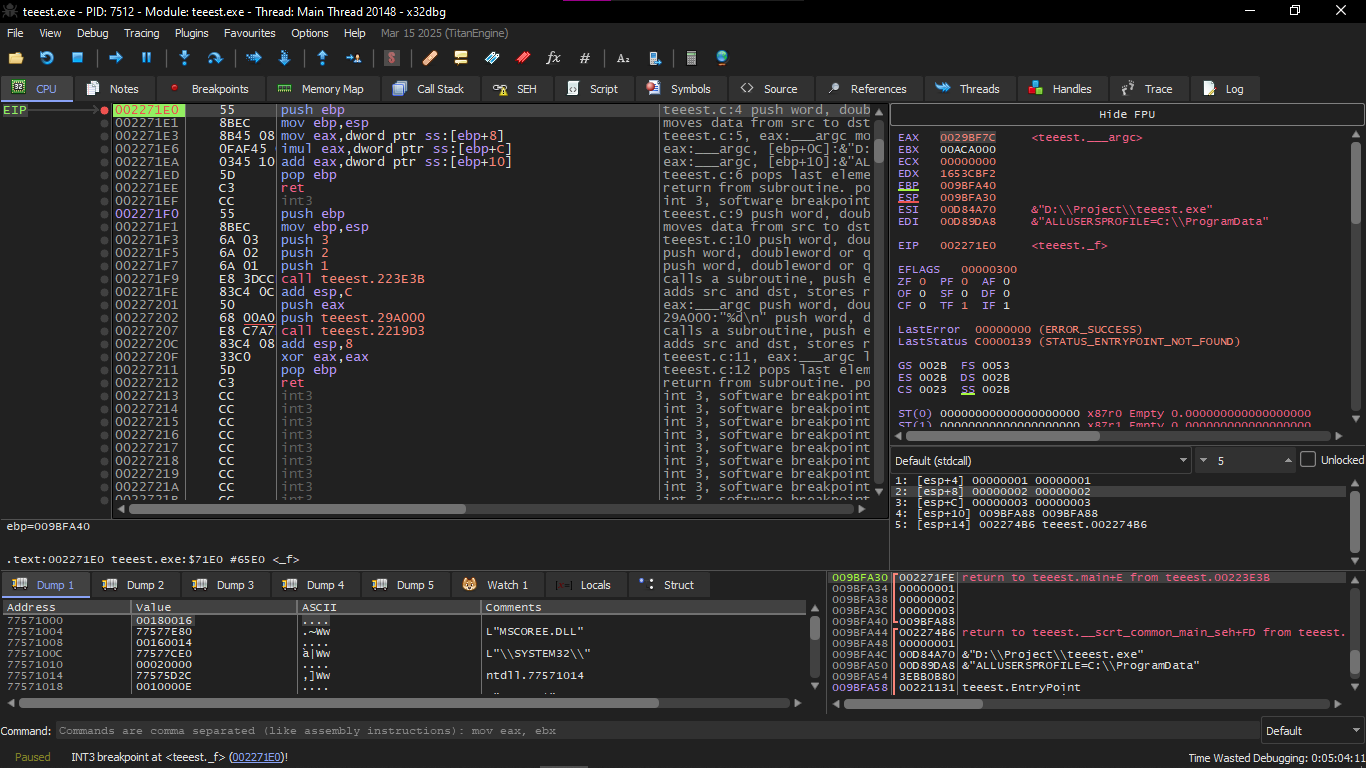

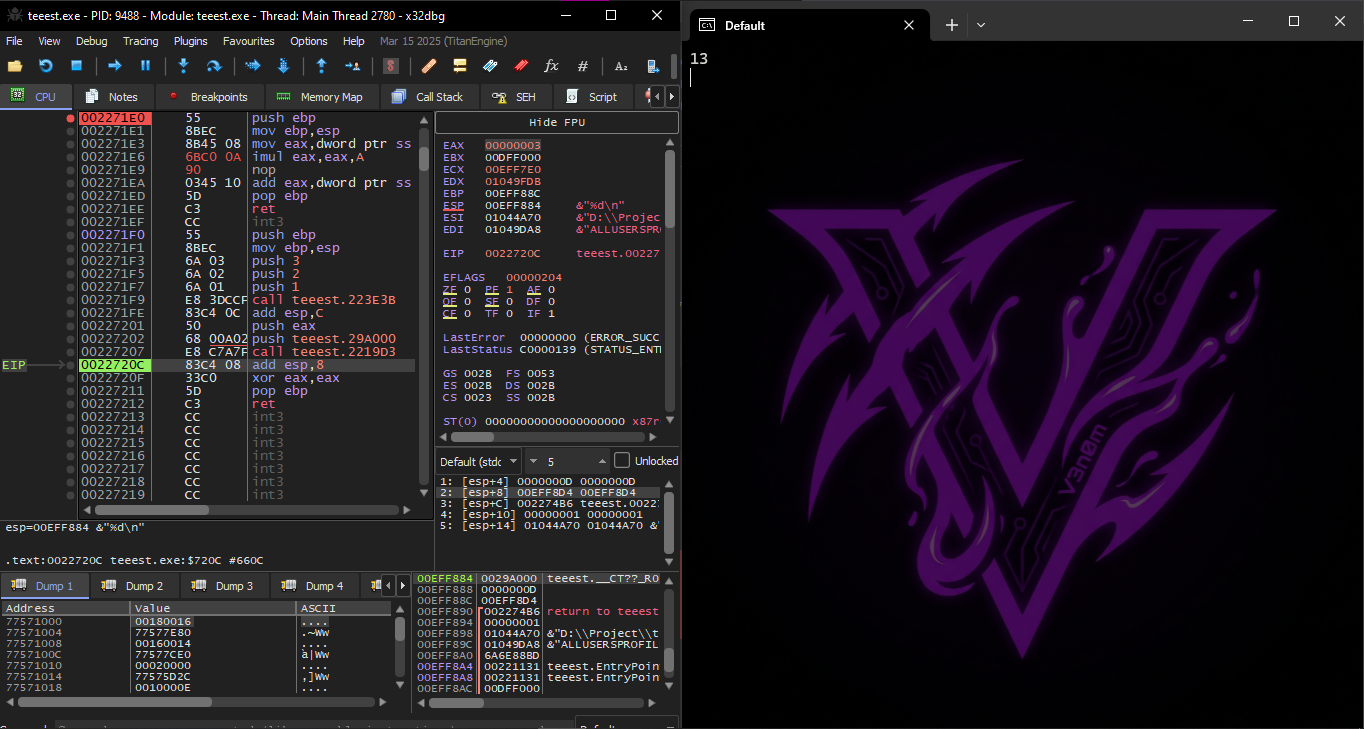

MSVC + OllyDbg

We will do this on the x32dbg as every time

We start first to compile the C with this Command:

cl /Zi /Od test.c ; compiles the C file test.c with debug information (/Zi) and optimization disabled (/Od)

After that, we start running it on x32 dbg and we set Breakpoint at Main

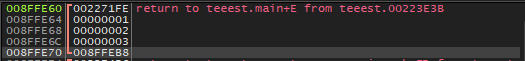

The first element in the stack frame is the stored old value of EBP, the second is RA (return address), the third is the first parameter in the function, then the second, then the third.

And I said to do another experiment to confirm my understanding of the Assembly code, which is that I wanted to make it output finally like 13 for example, and the supposed equation is a*b+c, and to return number 13, I had to change the b and make it 10 so that it becomes 1*10+3 = 13, and I changed it in this Instruction imul eax, dword ptr ss:[ebp+0x0C] and made it imul eax, eax,A and indeed it gave me the result I want

GCC

Let’s compile the same in GCC 4.4.1 and see the results in IDA:

;-------------------------

; Function: f

;------------------------- ; header comment for function f

public f ; declares f as public

f proc near ; starts the near procedure for f

arg_0 = dword ptr 8 ; 1st argument ; defines offset for first argument (at [EBP+8])

arg_4 = dword ptr 0Ch ; 2nd argument ; defines offset for second argument (at [EBP+0Ch])

arg_8 = dword ptr 10h ; 3rd argument ; defines offset for third argument (at [EBP+10h])

push ebp ; pushes EBP onto the stack to save previous base pointer

mov ebp, esp ; moves ESP to EBP, setting up stack frame

mov eax, [ebp+arg_0] ; load 1st argument ; moves first argument into EAX

imul eax, [ebp+arg_4] ; multiply by 2nd argument ; multiplies EAX by second argument

add eax, [ebp+arg_8] ; add 3rd argument ; adds third argument to EAX

pop ebp ; pops EBP to restore previous stack frame

retn ; returns from function

f endp ; ends the procedure for f

;-------------------------

; Function: main

;------------------------- ; header comment for function main

public main ; declares main as public

main proc near ; starts the near procedure for main

var_10 = dword ptr -10h ; defines local variable at [ESP-10h]

var_C = dword ptr -0Ch ; defines local variable at [ESP-0Ch]

var_8 = dword ptr -8 ; defines local variable at [ESP-8]

push ebp ; pushes EBP onto stack

mov ebp, esp ; sets EBP to ESP

and esp, 0FFFFFFF0h ; align stack ; aligns ESP to 16-byte boundary by ANDing with 0xFFFFFFF0

sub esp, 10h ; allocate 16 bytes ; subtracts 16 from ESP to allocate space

mov [esp+10h+var_8], 3 ; 3rd argument ; stores 3 at [ESP+8] (third argument for f)

mov [esp+10h+var_C], 2 ; 2nd argument ; stores 2 at [ESP+4] (second argument for f)

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 1 ; 1st argument ; stores 1 at [ESP] (first argument for f)

call f ; calls function f

mov edx, offset aD ; "%d\\n" ; moves address of format string to EDX

mov [esp+10h+var_C], eax ; result from f() ; stores result from f (in EAX) at [ESP+4] for printf

mov [esp+10h+var_10], edx ; stores format string address at [ESP] for printf

call _printf ; calls printf

mov eax, 0 ; sets EAX to 0 (return value)

leave ; leaves stack frame (mov esp, ebp; pop ebp)

retn ; returns from function

main endp ; ends the procedure for main

The result is almost like the previous one with some small differences we talked about before.

The stack pointer doesn't return to its place after the 2 functions (f and printf),

Because the LEAVE before the last one takes care of that in the end

1.14.2 x64

The story is a bit different in x86-64.

The arguments (first 4 or 6 of them) are sent through registers, meaning the callee reads them from registers not from the stack.

Listing 1.93: Optimizing MSVC 2012 x64 ; listing header

$SG2997 DB '%d', 0aH, 00H ; defines format string "%d\n" with null terminator

main PROC ; starts main procedure

sub rsp, 40 ; allocates 40 bytes on stack

mov edx, 2 ; sets EDX to 2 (second argument)

lea r8d, QWORD PTR [rdx+1] ; R8D = 3 ; loads 3 into R8D (third argument) using LEA (rdx+1)

lea ecx, QWORD PTR [rdx-1] ; ECX = 1 ; loads 1 into ECX (first argument) using LEA (rdx-1)

call f ; calls f

lea rcx, OFFSET FLAT:$SG2997 ; '%d' ; loads format string address into RCX

mov edx, eax ; moves result from f (in EAX) to EDX (second argument for printf)

call printf ; calls printf

xor eax, eax ; sets EAX to 0

add rsp, 40 ; restores stack by adding 40

ret 0 ; returns

main ENDP ; ends main

f PROC ; starts f procedure

; ECX - 1st argument ; comment: first arg in ECX

; EDX - 2nd argument ; comment: second arg in EDX

; R8D - 3rd argument ; comment: third arg in R8D

imul ecx, edx ; multiplies ECX by EDX, result in ECX

lea eax, DWORD PTR [r8+rcx] ; loads (r8 + rcx) into EAX using LEA

ret 0 ; returns

f ENDP ; ends f

Let's explain things in a simpler way

In x64 (64-bit) there is a new calling convention in Windows called Microsoft x64 calling convention.

This convention says first 4 arguments → are sent in registers

Meaning function f(a, b, c, d) receives them like this:

- a in ECX

- b in EDX

- c in R8D

- d in R9D

And this is what appears in the Assembly code above

And the LEA instruction here is used for addition, and the compiler clearly saw it as faster than ADD.

And also LEA was used in main() to prepare the first and third argument for function f(). The compiler probably decided that this would be faster than doing MOV.

Now let's see the non-optimizing version from MSVC:

Listing 1.94: MSVC 2012 x64 ; listing header

f proc near ; starts f

; shadow space: ; comment for shadow space

arg_0 = dword ptr 8 ; defines arg_0 at [RSP+8]

arg_8 = dword ptr 10h ; defines arg_8 at [RSP+10h]

arg_10 = dword ptr 18h ; defines arg_10 at [RSP+18h]

; ECX - 1st argument ; comment

; EDX - 2nd argument ; comment

; R8D - 3rd argument ; comment

mov [rsp+arg_10], r8d ; stores third arg (R8D) at [RSP+18h]

mov [rsp+arg_8], edx ; stores second arg (EDX) at [RSP+10h]

mov [rsp+arg_0], ecx ; stores first arg (ECX) at [RSP+8]

mov eax, [rsp+arg_0] ; loads first arg into EAX

imul eax, [rsp+arg_8] ; multiplies EAX by second arg

add eax, [rsp+arg_10] ; adds third arg to EAX

retn ; returns

f endp ; ends f

main proc near ; starts main

sub rsp, 28h ; allocates 40 bytes (0x28h) on stack

mov r8d, 3 ; 3rd argument ; sets R8D to 3

mov edx, 2 ; 2nd argument ; sets EDX to 2

mov ecx, 1 ; 1st argument ; sets ECX to 1

call f ; calls f

mov edx, eax ; moves result to EDX for printf

lea rcx, $SG2931 ; "%d\\n" ; loads format string into RCX

call printf ; calls printf

; return 0 ; comment

xor eax, eax ; sets EAX to 0

add rsp, 28h ; restores stack

retn ; returns

main endp ; ends main

The view is a bit confusing because the 3 arguments coming from registers were stored in the stack for some reason.

This is called "Shadow Space":

shadow space = 4 places reserved on the stack always before any call in x64

Why? For two things?

- Every function in Windows must expect that there is space on the stack ready to receive the 4 arguments even if there are no arguments at all and this makes it easier for the debugger and ABI.

- The function can copy the parameters from registers to the stack if it needs to use them as variables

And this we saw here:

mov [rsp+arg_10], r8d ; copy 3rd arg ; stores R8D (third arg) to shadow space

mov [rsp+arg_8], edx ; copy 2nd arg ; stores EDX (second arg) to shadow space

mov [rsp+arg_0], ecx ; copy 1st arg ; stores ECX (first arg) to shadow space

GCC

The GCC which is made for Optimization outputs somewhat understandable code:

f: ; label for function f

; EDI - 1st argument ; comment: first arg in EDI

; ESI - 2nd argument ; comment: second arg in ESI

; EDX - 3rd argument ; comment: third arg in EDX

imul esi, edi ; multiplies ESI by EDI, result in ESI

lea eax, [rdx + rsi] ; loads (RDX + RSI) into EAX using LEA

ret ; returns

main: ; label for main

sub rsp, 8 ; allocates 8 bytes on stack

mov edx, 3 ; sets EDX to 3 (third arg)

mov esi, 2 ; sets ESI to 2 (second arg)

mov edi, 1 ; sets EDI to 1 (first arg)

call f ; calls f

mov edi, OFFSET FLAT:.LC0 ; "%d\\n" ; sets EDI to format string address

mov esi, eax ; sets ESI to result from f

xor eax, eax ; number of vector registers passed ; zeros EAX (for vector registers count)

call printf ; calls printf

xor eax, eax ; zeros EAX (return 0)

add rsp, 8 ; restores stack

ret ; returns

Non-optimizing GCC

f: ; label for f

; EDI - Argument ; comment: first arg in EDI

; ESI - Argument ; comment: second arg in ESI

; EDX - Argument ; comment: third arg in EDX

push rbp ; pushes RBP

mov rbp, rsp ; sets RBP to RSP

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], edi ; stores first arg at [RBP-4]

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-8], esi ; stores second arg at [RBP-8]

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-12], edx ; stores third arg at [RBP-12]

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-4] ; loads first arg into EAX

imul eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-8] ; multiplies EAX by second arg

add eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-12] ; adds third arg to EAX

leave ; leaves frame

ret ; returns

main: ; label for main

push rbp ; pushes RBP

mov rbp, rsp ; sets RBP to RSP

mov edx, 3 ; sets EDX to 3

mov esi, 2 ; sets ESI to 2

mov edi, 1 ; sets EDI to 1

call f ; calls f

mov edx, eax ; moves result to EDX

mov eax, OFFSET FLAT:.LC0 ; "%d\\n" ; sets EAX to format string

mov esi, edx ; sets ESI to result

mov rdi, rax ; sets RDI to format string (from EAX)

mov eax, 0 ; sets EAX to 0 (vector registers)

call printf ; calls printf

mov eax, 0 ; sets EAX to 0

leave ; leaves

ret ; returns

There is no such thing as Shadow Space in System V of UNIX systems, but the callee (the function that was called) can save the arguments in the place it wants if there is a shortage in registers.

GCC: uint64_t instead of int

Our example works on int 32-bit, that's why the code uses 32-bit parts of registers that start with (E).

We can change it a bit to work with 64-bit values:

#include <stdio.h> ; includes stdio.h

#include <stdint.h> ; includes stdint.h for uint64_t

uint64_t f (uint64_t a, uint64_t b, uint64_t c) ; defines f with uint64_t types

{

return a*b+c; ; returns a*b + c

};

int main() ; main function

{

printf ("%lld\\n", f(0x1122334455667788, ; calls printf with f result

0x1111111122222222,

0x3333333344444444));

return 0; ; returns 0

};

Listing 1.97: Optimizing GCC 4.4.6 x64

f proc near ; starts f

imul rsi, rdi ; multiplies RSI by RDI

lea rax, [rdx+rsi] ; loads (RDX + RSI) into RAX

retn ; returns

f endp ; ends f

main proc near ; starts main

sub rsp, 8 ; allocates 8 bytes

mov rdx, 3333333344444444h ; 3rd argument ; sets RDX to 0x3333333344444444

mov rsi, 1111111122222222h ; 2nd argument ; sets RSI to 0x1111111122222222

mov rdi, 1122334455667788h ; 1st argument ; sets RDI to 0x1122334455667788

call f ; calls f

mov edi, offset format ; "%lld\\n" ; sets EDI to format string

mov rsi, rax ; sets RSI to result

xor eax, eax ; number of vector registers passed ; zeros EAX

call _printf ; calls printf

xor eax, eax ; zeros EAX

add rsp, 8 ; restores stack

retn ; returns

main endp ; ends main

The code is the same,

The only difference is that this time the full registers (that start with R-) are the ones used

1.14.3 ARM

Non-optimizing Keil 6/2013 (ARM mode)

.text:000000A4 00 30 A0 E1 MOV R3, R0 ; moves the value from R0 (first argument) to R3

.text:000000A8 93 21 20 E0 MLA R0, R3, R1, R2 ; multiplies R3 by R1, adds R2, and stores the result in R0

.text:000000AC 1E FF 2F E1 BX LR ; branches to the address in LR (return), possibly switching mode

.text:000000B0 main ; starts the main function

.text:000000B0 10 40 2D E9 STMFD SP!, {R4, LR} ; stores R4 and LR on the stack (decrement before)

.text:000000B4 03 20 A0 E3 MOV R2, #3 ; sets R2 to 3 (third argument)

.text:000000B8 02 10 A0 E3 MOV R1, #2 ; sets R1 to 2 (second argument)

.text:000000BC 01 00 A0 E3 MOV R0, #1 ; sets R0 to 1 (first argument)

.text:000000C0 F7 FF FF EB BL f ; branches to f and links (calls f)

.text:000000C4 00 40 A0 E1 MOV R4, R0 ; moves the result from R0 to R4

.text:000000C8 04 10 A0 E1 MOV R1, R4 ; moves R4 (result) to R1 (argument for printf)

.text:000000CC 5A 0F 8F E2 ADR R0, aD_0 ; "%d\\n" ; gets the address of the format string into R0

.text:000000D0 E3 18 00 EB BL __2printf ; calls printf

.text:000000D4 00 00 A0 E3 MOV R0, #0 ; sets R0 to 0 (return value)

.text:000000D8 10 80 BD E8 LDMFD SP!, {R4, PC} ; loads R4 and PC from stack (return)

The main() function simply calls two functions, and sends 3 values to the first function — which is f().

As we said before, in ARM the first 4 values are usually sent in the first 4 registers (R0-R3).

And function f(), as seen, uses the first 3 registers (R0–R2) as arguments.

The MLA (Multiply Accumulate) instruction multiplies the first two operands (R3 and R1), then adds the third (R2), and places the result in the zero register (R0), and it's like this:

R0 = R3 * R1 + R2

Multiplication and addition at once (Fused multiply–add) is a very useful operation. By the way, there was no such instruction in x86 before the FMA-instructions appeared in SIMD.

The first instruction MOV R3, R0 seems redundant (could do one MLA and done).

The compiler didn't do Optimization for it because we are here in non-optimizing compilation.

The BX instruction returns control to the address stored in LR, and if needed, changes the processor mode from Thumb to ARM or vice versa.

And this may be necessary, because as you see, the function f() doesn't know it might be called from ARM code or Thumb code.

So if someone called it from Thumb, the BX instruction not only returns control, it also returns the mode to Thumb.

And if it's called from ARM then it doesn't change anything.

Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (ARM mode)

.text:00000098 f ; starts function f

.text:00000098 91 20 20 E0 MLA R0, R1, R0, R2 ; multiplies R1 by R0, adds R2, stores in R0

.text:0000009C 1E FF 2F E1 BX LR ; returns to LR, possibly switching mode

In the -O3 the function f() was assembled like this:

Here MOV was removed (or reduced), and MLA now uses all the input registers and places the result directly in R0 — which is the place the caller will read it from directly

Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (Thumb mode)

.text:0000005E 48 43 MULS R0, R1 ; multiplies R0 by R1, sets flags, result in R0

.text:00000060 80 18 ADDS R0, R0, R2 ; adds R2 to R0, sets flags

.text:00000062 70 47 BX LR ; returns to LR

The MLA instruction is not available in Thumb mode, so compiler generates code that does the two operations (multiplication and addition) each separately.

The first instruction MULS multiplies R0 × R1, and places the result in R0.

The second instruction ADDS adds the result with R2 and leaves the result in R0.

ARM64

Optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

Everything here is simple.

The MADD instruction is just an instruction that does multiplication + addition at the same time (similar to the MLA we saw before). The three arguments are sent in the 32-bit part of the X-registers. Indeed, the variable types are 32-bit ints.

The result is returned in W0.

f: ; starts function f

madd w0, w0, w1, w2 ; multiplies w0 by w1, adds w2, stores in w0

ret ; returns

main: ; starts main

; save FP and LR to stack frame ; comment

stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]! ; stores x29 (FP) and x30 (LR) on stack, decrements SP by 16

mov w2, 3 ; sets w2 to 3 (third argument)

mov w1, 2 ; sets w1 to 2 (second argument)

add x29, sp, 0 ; sets x29 to current SP (frame pointer)

mov w0, 1 ; sets w0 to 1 (first argument)

bl f ; branches to f and links (calls f)

mov w1, w0 ; moves result from w0 to w1 (for printf)

adrp x0, .LC7 ; gets page address of .LC7 into x0

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC7 ; adds low 12 bits to get full address of format string

bl printf ; calls printf

; return 0 ; comment

mov w0, 0 ; sets w0 to 0

; restore FP & LR ; comment

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16 ; loads x29 and x30 from stack, increments SP by 16

ret ; returns

.LC7: ; label for string

.string "%d\\n" ; defines the format string "%d\n"

Now we extend all data types to 64-bit uint64_t and try:

f: ; starts f

madd x0, x0, x1, x2 ; multiplies x0 by x1, adds x2, stores in x0

ret ; returns

main: ; starts main

mov x1, 13396 ; moves lower part of value to x1

adrp x0, .LC8 ; gets page address of .LC8

stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]! ; saves FP and LR

movk x1, 0x27d0, lsl 16 ; moves next 16 bits to x1 shifted left by 16

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC8 ; adds low bits for format string

movk x1, 0x122, lsl 32 ; moves next 16 bits shifted left by 32

add x29, sp, 0 ; sets FP

movk x1, 0x58be, lsl 48 ; moves upper 16 bits shifted left by 48

bl printf ; calls printf

mov w0, 0 ; sets w0 to 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16 ; restores FP and LR

ret ; returns

.LC8: ; label

.string "%lld\\n" ; defines "%lld\n"

Non-optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

f: ; starts f

sub sp, sp, #16 ; subtracts 16 from SP (allocates space)

str w0, [sp,12] ; stores w0 (first arg) at [SP+12]

str w1, [sp,8] ; stores w1 (second arg) at [SP+8]

str w2, [sp,4] ; stores w2 (third arg) at [SP+4]

ldr w1, [sp,12] ; loads first arg into w1

ldr w0, [sp,8] ; loads second arg into w0

mul w1, w1, w0 ; multiplies w1 by w0, result in w1

ldr w0, [sp,4] ; loads third arg into w0

add w0, w1, w0 ; adds w1 to w0, result in w0

add sp, sp, 16 ; adds 16 to SP (deallocates)

ret ; returns

The code here saves the input arguments in the local stack, in case someone (or something) inside the function needs to use the registers W0…W2.

This prevents the original arguments from being overwritten because they might be needed again later.

And this is called Register Save Area.

From Procedure Call Standard for ARM64 (AArch64), 2013.

But the callee is not obligated to save them.

And this is a bit like the “Shadow Space” in: 1.14.2 page 129.

Why did the optimizing GCC 4.9 remove all the argument saving code?

Because it did extra optimization and concluded that arguments won't be needed again, and the registers W0…W2 won't be used.

And also we saw a pair of MUL / ADD instructions instead of one MADD.

1.14.4 MIPS

Optimizing GCC 4.4.5

.text:00000000 f: ; starts function f

; $a0 = a ; comment: first arg in $a0

; $a1 = b ; comment: second arg in $a1

; $a2 = c ; comment: third arg in $a2

mult $a1, $a0 ; multiply a0 * a1 ; multiplies $a1 by $a0, result in HI:LO

mflo $v0 ; get low 32 bits of result into v0 ; moves low part of multiplication result to $v0

jr $ra ; return ; jumps to return address in $ra

addu $v0, $a2, $v0 ; branch delay slot: v0 = v0 + c ; adds $a2 to $v0 (in delay slot)

; result returned in $v0 ; comment

.text:00000010 main: ; starts main

var_10 = -0x10 ; defines local var_10

var_4 = -4 ; defines local var_4

lui $gp, (__gnu_local_gp >> 16) ; loads upper 16 bits of __gnu_local_gp into $gp

addiu $sp, -0x20 ; subtracts 0x20 from $sp (allocates stack)

la $gp, (__gnu_local_gp & 0xFFFF) ; loads lower part of __gnu_local_gp into $gp

sw $ra, 0x20+var_4($sp) ; stores $ra at [SP + 0x1C]

sw $gp, 0x20+var_10($sp) ; stores $gp at [SP + 0x10]

; set c ; comment

li $a2, 3 ; loads 3 into $a2 (third arg)

; set a ; comment

li $a0, 1 ; loads 1 into $a0 (first arg)

jal f ; call f() ; jumps to f and links

li $a1, 2 ; branch delay slot: set b ; loads 2 into $a1 (second arg) in delay slot

; result now in $v0 ; comment

lw $gp, 0x20+var_10($sp) ; loads $gp from [SP + 0x10]

lui $a0, ($LC0 >> 16) ; loads upper bits of $LC0 into $a0

lw $t9, (printf & 0xFFFF)($gp) ; loads printf address into $t9

la $a0, ($LC0 & 0xFFFF) ; loads lower part of $LC0 into $a0

jalr $t9 ; jumps to printf address in $t9

move $a1, $v0 ; branch delay slot: pass result to printf ; moves $v0 to $a1 (argument for printf)

lw $ra, 0x20+var_4($sp) ; loads $ra from [SP + 0x1C]

move $v0, $zero ; sets $v0 to 0

jr $ra ; jumps to $ra (return)

addiu $sp, 0x20 ; branch delay slot: restore stack ; adds 0x20 to $sp

The first four arguments for the function are sent in 4 registers, which are the registers that start with A-.

There are two special registers in the MIPS architecture:

HI and LO — these are where the 64-bit multiplication result is placed while MULT is running.

These registers can only be accessed using MFLO and MFHI instructions.

Here MFLO takes the low part of the multiplication result and places it in $v0.

The high part of the multiplication result (in HI) is discarded.

And this is normal because we are dealing with 32-bit int.

And then the ADDU instruction (“addition without sign”) adds the value of the third argument to the result.

There are two addition instructions in MIPS: ADD and ADDU.

The difference is not in signed or unsigned…

The difference is that ADD can do exception if overflow occurs, and this is sometimes useful.

But ADDU doesn't do exceptions.

And since C/C++ doesn't do exceptions in overflow,

That's why they used ADDU.

The 32-bit result is left in $v0.

In main() there is a new instruction: JAL (“Jump and Link”).

The difference between it and JALR:

- The JAL has a relative offset (relative address).

- The JALR jumps to the address inside a register.

And since f() and main() are in the same file, then the relative address of f is fixed and known.