Reverse Engineering for Beginners : More about results returning

1.15 More about results returning

The author said that in x86, the result of function execution is usually returned in the EAX register. If the type is byte or char, the lower part of the EAX register which is AL is used. If the function returns a float number, the FPU register ST(0) is used. In ARM, the result is usually returned in the R0 register.

1.15.1 Attempt to use the result of a function returning void

Well, what happens if the return value of main() was void not int?

The so-called startup-code calls main() approximately like this:

In other words

If you wrote void main() instead of int main(), what happens?

void main()means that no value is expected to be returned explicitly. But theEAXregister may contain any meaningless value (leftover) from previous instructions.- When the startup code does

push eaxaftercall main, it will send the value inEAXtoexit()— and therefore the exit code will be a random value or a value from the last executed function (likeputs()orprintf()if used).

We can illustrate this with code like this:

GCC here might replace printf with puts.

puts()returns the number of characters it printed inEAX. If main didn't return a value,EAXwill retain this value.

We write a bash script that displays the exit status:

Listing 1.101: tst.sh

And we run it:

$ tst.sh Hello, world! 14

14 is the number of characters that were printed.

The number of characters leaked from printf() (or puts) through EAX/RAX and entered as “exit code”.

By the way, when we decompile C++ with Hex-Rays, sometimes we encounter a function that ends with a class destructor:

According to the C++ standard, the destructor does not return anything, but when Hex-Rays does not know that, and thinks that the destructor and the function itself return int, we see something like this in the outputs:

In a clearer sense, it is that when Hex-Rays saw retn, it said that surely this Function returns a Value even though in reality this is just a return to the Caller, nothing more.

1.15.3 Returning a structure

The author then explained and said the truth is that the return value is computed in the EAX register.

And without much chatter, the reason is that old C compilers could not make a function return something that does not fit in one register (usually int)

If one needs to return something bigger, he must return the data through pointers sent as arguments to the function.

So it is very normal that a function returns one value only, and the rest returns it through pointers.

Now we can return a full struct, but the subject is not famous.

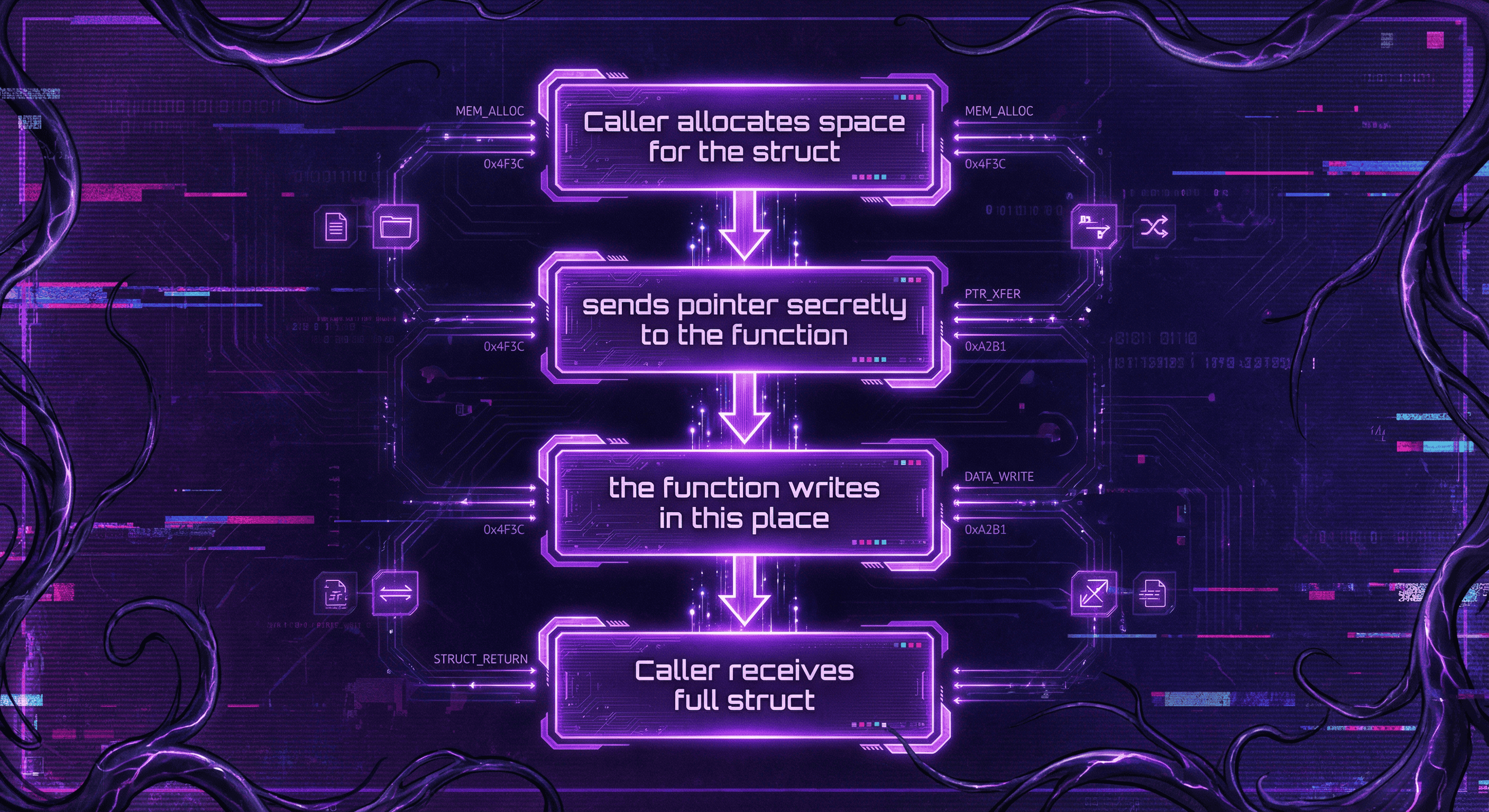

If a function must return a large struct, the function that calls it (the caller) must allocate it and send a pointer to it as the first argument, and this happens hidden from the programmer.

Meaning it is the same idea as if you send a pointer in the first argument by hand, but the compiler hides this.

A small example:

What we got (MSVC 2010 /Ox):

The micro that the compiler uses here to pass the pointer to the struct is named $T3853.

We can write the same example using C99:

- GCC 4.8.1:

As we see, the function fills the fields of the struct that was allocated before by the calling function, as if a pointer to the struct was sent as an argument.

So there is no loss in performance.

To make this part easier for you, I'll explain with a simple explanation that clarifies things a bit.

First, this is the big instruct will be in this shape for example

This will be its shape in memory

┌─────────┐ │ a │ ├─────────┤ │ b │ ├─────────┤ │ c │ └─────────┘

The caller now before calling the function get_some_values(a)

He does this, allocates a place for the struct in memory like this

Caller Memory: ┌──────────────────────────┐ │ Empty space to save struct │ ← It will be returned here │ Address = 5000 │ └──────────────────────────┘

And after that sends the address of this place to the function as a hidden argument

Caller │ │ sends pointer = 5000 ▼ Callee (get_some_values)

At that time the function receives a pointer to an empty place and starts writing the values inside it

Address 5000: ┌─────────┐ │ a=a+1 │ ├─────────┤ │ b=a+2 │ ├─────────┤ │ c=a+3 │ └─────────┘

And this is the final shape

Caller memory:

┌────────────────────────────┐

│ struct at 5000: │

│ a = a+1 │

│ b = a+2 │

│ c = a+3 │

└────────────────────────────┘

↑

│

callee wrote the values here

After now the function finishes, the function does not return the struct directly, she returns the pointer that you originally sent (hidden)

So the caller sees the full struct appeared to him:

return value ← same address 5000 Caller now sees: a = a+1 b = a+2 c = a+3

And this is a summary for all this talk