Reverse Engineering for Beginners : 1.12 scanf()(CH1.11) {Part1}

scanf()

Let's make an example like this on scanf()

The author explained at that time and said that it is not smart to use scanf() to deal with the user these days. But we can, nevertheless, illustrate how to pass a pointer to an int type variable

About pointers

The author said at that time and explained and said that pointers are one of the basic concepts in computer science because simply when you have large data (like arrays or objects), passing them as a copy to another function takes time and space But if you send only its address, then you save time and space and the function can access it directly He gave an example on the Pointer and said: If you are going to print a string on the console, it is much easier to send its address to the OS kernel. Also, if the function that is called needs to modify the large array or structure that it received as a parameter and then return the entire structure, then the matter becomes almost absurd. So the simplest thing we can do is to send the address of the array or structure to the called function, and leave it to change what it needs to change.

Well, if you still don't understand, I will explain the matter to you more:

This is an example I used to clarify things a bit

To understand what happened here one by one, focus with me:

In the main function, we have a variable with value 5, then we print this value, then we send the address of x to a function called changeValue using &x, then inside the function called changeValue, we use the Pointer to change the value that this address points to, so the value of X changes from 5 to 20 So here, instead of sending the value of x to another function, we send its address, and this allows the function to change the value directly in memory without needing to return the modified value from the function

In x86, the address is represented as a 32-bit number (taking 4 bytes), and in x86-64 it is 64-bit (taking 8 bytes). By the way, this is the reason that makes some people annoyed by the transition to x86-64 — all pointers in x64 architecture need double space, including the cache memory which is "expensive" memory

We can work with Untyped pointers but with a little effort

Well, let's first understand what Untyped pointers are and then explain with effort why Untyped pointers are pointers that are not linked to a specific type of data. This means that you do not have to specify the type of data that this pointer will point to

We can take an example in C, which is that there is a function called memcpy() that copies a block from one place in memory to another, it takes 2 pointers of type void* as arguments, because it is impossible to predict the type of data you want to copy. The type of data is not important, what matters is the size of the block

And also I will make you understand more and give you the example in the code so you don't get lost from me Look, this is a code here in the function that has memcpy()

Here memcpy() takes 3 things:

- destination - and to simplify things for you, the place where we will copy the data to.

- source - and this is the place from which we will copy the data.

- size - how much space we will transfer (number of bytes).

The void* pointer: memcpy() function takes pointers of type void* so that it can copy any type of data, not necessarily numbers

Pointers are also used a lot when a function needs to return more than one value and we will explain this later

The scanf() function — an example of this case.

Besides needing to say how many values were read successfully, it also needs to return all these values.

In C/C++ the pointer type is required only for compile-time type checking.

Inside the compiled code there is no information about pointer types at all

x86

.png)

Here is what we get after compiling with MSVC 2010:

Here the X was a local variable

According to C/C++ standard it must be visible only inside this function and not from any other external scope.

Traditionally, the local variables are stored on the stack. There are possible other ways to store them, but in x86 this is the way.

In the instruction which is

Here this allocates 4 bytes value for the variable X and it is here not existing to save the state of ECX

Because originally there is no POP ECX at the end of the Function

And the variable X is accessed with the help of the macro _x$ (its value -4) and the register EBP which points to the current frame.

During the execution of the function, EBP is pointing to the current stack frame, and this facilitates access to the local variables and the arguments through EBP+offset .

We can use ESP for the same purpose, but this is not comfortable because it changes a lot. The value of EBP can be seen as if it is a "frozen" copy of the value of ESP at the beginning of the execution of the function.

Here is a typical shape for the stack frame in a 32-bit environment:

In our example now the Scanf() function has 2 arguments

The first is a pointer to the string that has %d and the second is the address of the variable x.

First thing the address of x is put in register EAX with the instruction:

lea eax, DWORD PTR _x$[ebp]

LEA abbreviation for load effective address , and often used to form an address.

We can say that in this case LEA stores the sum of the value of EBP and the macro _x$ inside EAX .

And this is the same thing as:

lea eax, [ebp-4]

Meaning it subtracts 4 from the value of EBP and throws the result in EAX.

After that the value of EAX is done push on the stack and scanf() is called.

After that printf() is called with the first argument — pointer to the string:

"You entered %d...\n"

The second argument is prepared with:

mov ecx, [ebp-4]

This instruction puts the value of x not its address inside ECX.

And after that the value of ECXis pushed on the stack and the last printf() is called.

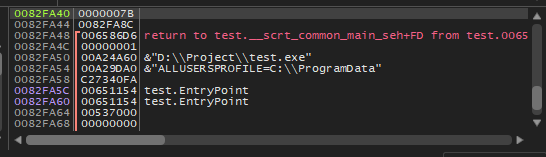

MSVC + OllyDbg

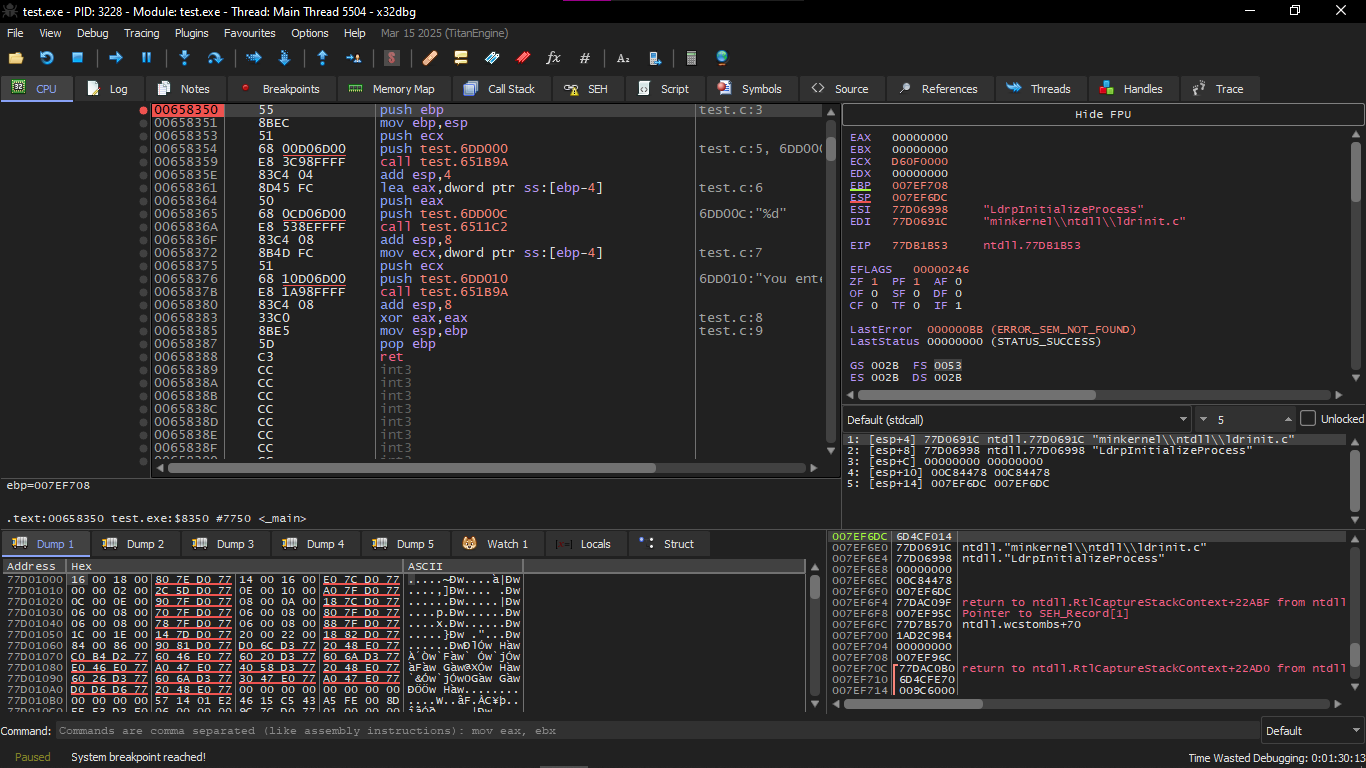

The author began to use this example on OllyDbg but of course I did it on X32dbg so I will explain it on it and explain it in details.

Initially after you write the C code you will start to compile it using the command:

So that you also understand the command:

- /Od → prevents the optimizer

- /Zi → makes debug symbols clear

and this will make the code similar to the one in the book exactly

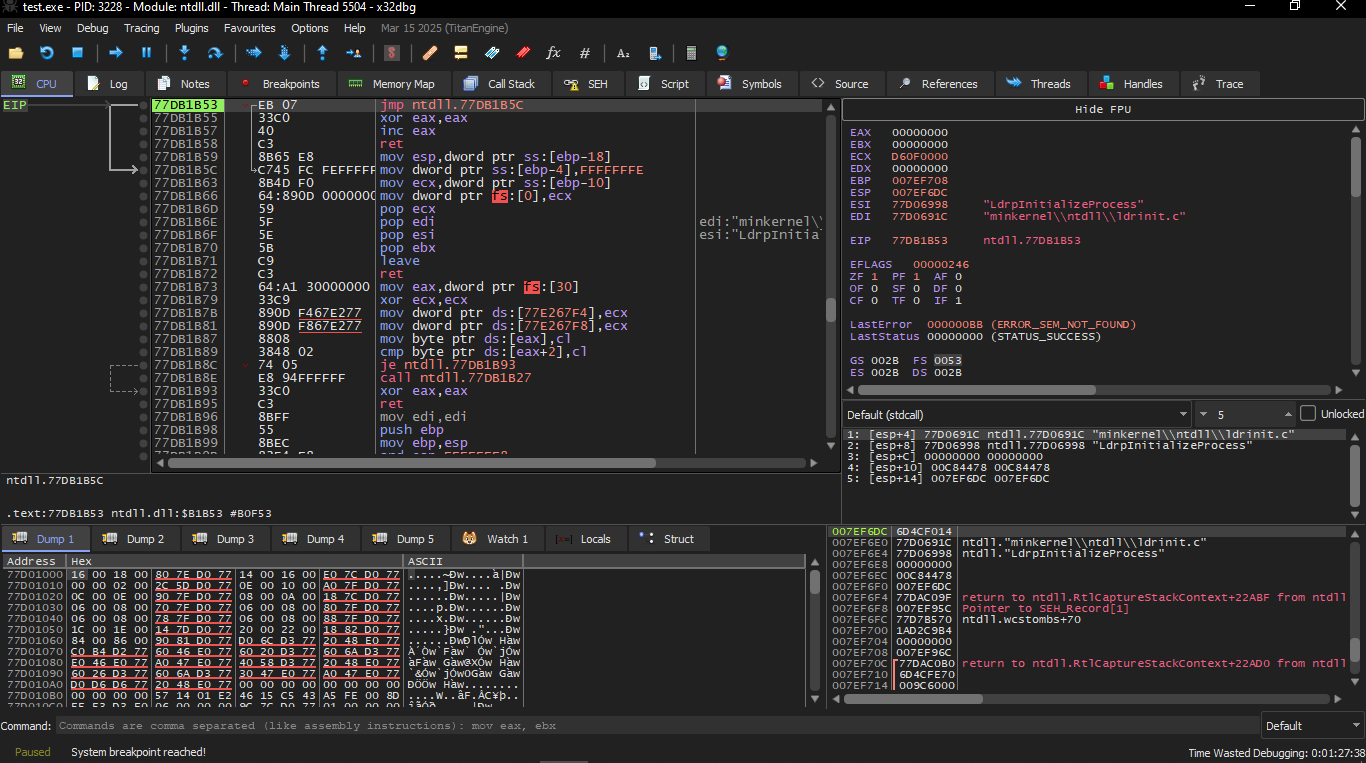

We start opening it on the X32dbg and we will notice that we are first inside the ntdll.ll

We go also to the Symbols and search for the main it will start to show the code we want

We will make at PUSH EBP Breakpoint by marking it and pressing on F9

After that you will keep pressing F9 to reach it

In the instruction which is push test.6DD000 this you will find it putting the address of this text Enter X:\n

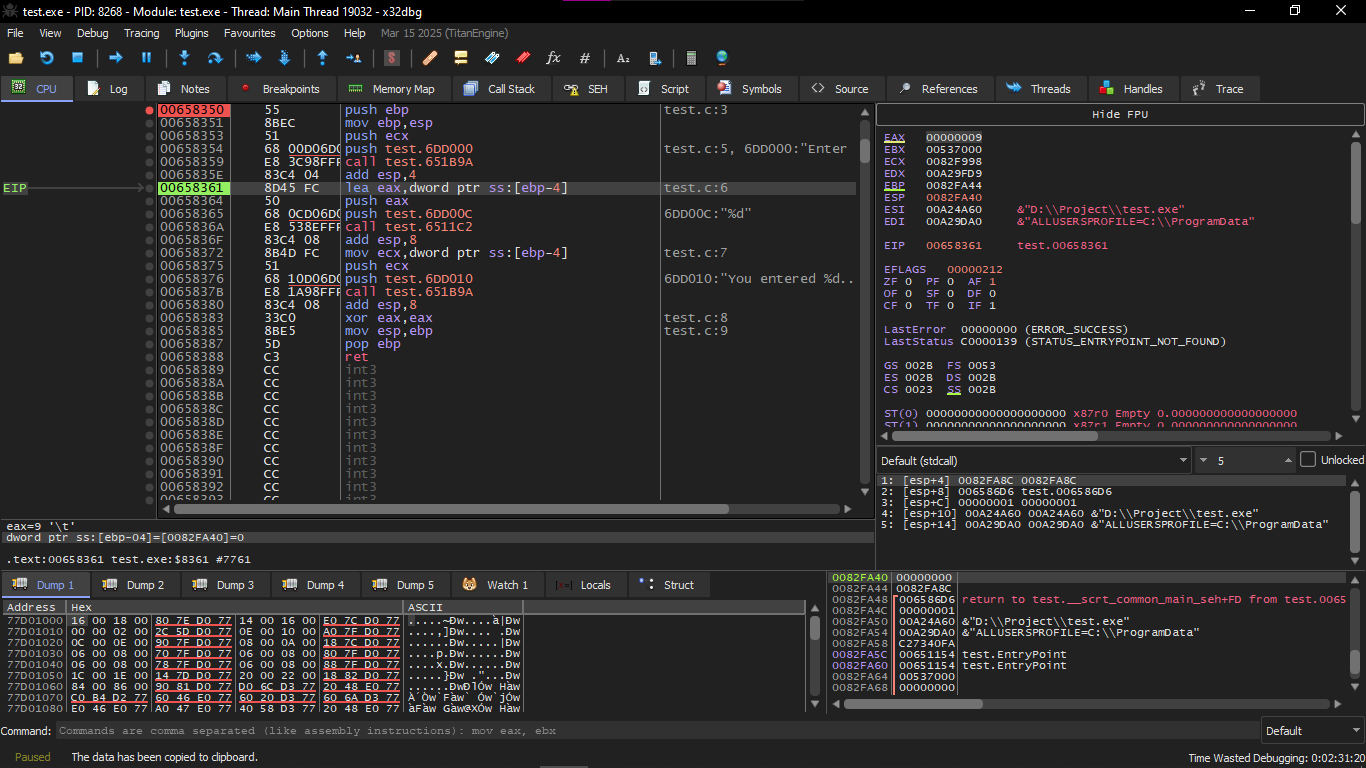

In the instruction lea eax, [ebp-4] here is the step where the CPU puts the address of the variable x and puts it inside EAX

At the instruction call test.6511c2 here is the place where you enter your variable in the Console and let's say I put 123

As soon as we went to the instruction mov ecx,dword ptr ss:[ebp-4] you will find in the Stack like this

Which is the Value 0x7B which is 123 but in Hex

GCC

Let’s try compiling this code with GCC 4.4.1 under Linux:

GCC replaced the printf("Enter X:\n") call with a call to puts() — the reason for this was explained before: puts is lighter, faster, and simpler than printf when no formatting is needed.

Just like in MSVC examples — arguments are placed on the stack using MOV instead of PUSH.

This simple example is a great demo of the fact that the compiler translates a sequence of expressions in a C/C++ block into a sequential list of machine instructions. There is nothing between the expressions in C/C++ — and therefore in the resulting machine code… there is nothing between them either. The control flow simply slides from one expression to the next.

MSVC 2012 x64

Optimizing GCC 4.4.6 x64

ARM: Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (Thumb mode)

For scanf() to read the input, it needs a pointer to an int — and since int is 32-bit, we only need 4 bytes in memory. This could fit in a register, but here the local variable x is placed on the stack (IDA named it var_8).

There was no need to explicitly allocate space — because after PUSH {R3,LR}, the SP already points to free space on the stack. So we can use it directly. That’s why MOV R1, SP is used — it passes the address of x to scanf().

Note: PUSH and POP in ARM work opposite to x86 — they are synonyms for:

STMDB(Store Multiple Decrement Before)LDMIA(Load Multiple Increment After)

PUSH writes first, then decrements SP.POP increments SP first, then reads. So after PUSH, SP points to free space — perfect for scanf() and printf() to use. Then using LDR, the value is loaded back from the stack into R1 to pass to printf().ARM64: Non-optimizing GCC 4.9.1

Here the compiler allocated 32 bytes for the stack frame — even though we only need 4 bytes for x — most likely for alignment reasons.

The most important part is where the variable x is stored (line with add x1, x29, 28). Why 28? Because the compiler decided to place the variable at the end of the stack frame instead of the beginning. The address is passed to scanf(), which writes the user input there. Then the value (32-bit int) is loaded back at ldr w1, [x29,28] and passed to printf().

1.12.2 The classic mistake

This is a very famous mistake (or typing error) that you pass the value of x instead of passing the pointer to x:

I will tell you what happens here

x is not initialized and has some random noise (garbage) from the local stack.

When scanf() is called, it takes the string from the user, converts it to a number, and tries to write that number into x… but treating x as if it were an address in memory

At that time, of course, a Crash will occur

Let me explain it to you in a simpler way:

Suppose that X has a random number like this for example:

Then scanf will understand that this is an address in memory and go to write on it.

Where does it write?

In 0x41414141

And this is of course an empty/reserved/not allowed address. So the code crashes.

The nice thing is that some CRT libraries in debug mode put a distinctive pattern in the memory that has not been allocated yet, like 0xCCCCCCCC or 0x0BADF00D and such. In this case, x may have 0xCCCCCCCC inside it, and scanf() will try to write to this address 0xCCCCCCCC.

And if you notice that there is something in the process trying to write to 0xCCCCCCCC, you know that there is a variable (or pointer) that is not initialized and was used before it was initialized. And this is better than the new memory being all zeros