1.21 Loops

x86

The author began this section by saying that there is a special instruction called LOOP in the x86 instruction set.

This instruction checks the value in the ECX register; if it is not zero, it decrements ECX by one and transfers control to the label specified in the LOOP operand.

Generally, this instruction is not very convenient, and modern compilers do not generate it automatically.

Therefore, if you see this instruction in code, it is highly likely that the code is hand-written Assembly.

In C/C++, loops are usually implemented using:

Let us start with for().

This statement specifies:

- Loop initialization (setting the initial value of the counter)

- Loop condition (is the counter greater or less than a certain limit?)

- What happens at each iteration (increment or decrement)

- And of course, the loop body

The general form:

for (initialization; condition; at_each_iteration) // general form of for loop

{

loop_body; // the body of the loop

};

The generated code also consists of four parts.

Let us start with a simple example:

#include <stdio.h> // include standard I/O header file

void printing_function(int i) // define function that takes int parameter i

{

printf ("f(%d)\n", i); // print "f(value_of_i)" followed by newline

};

int main() // program entry point

{

int i; // declare integer variable i

for (i=2; i<10; i++) // loop: start i=2, continue while i<10, increment i each iteration

printing_function(i); // call printing_function with current i

return 0; // return 0 to indicate successful termination

};

Result (MSVC 2010):

_i$ = -4 ; offset of local variable i on stack

_main PROC

push ebp ; save base pointer (standard prologue)

mov ebp, esp ; set up stack frame

push ecx ; allocate 4 bytes for local variable i

mov DWORD PTR _i$[ebp], 2 ; initialization: set i = 2

jmp SHORT $LN3@main ; jump to condition check

$LN2@main:

mov eax, DWORD PTR _i$[ebp] ; load current i into EAX

add eax, 1 ; increment i

mov DWORD PTR _i$[ebp], eax ; store incremented value back to i

$LN3@main:

cmp DWORD PTR _i$[ebp], 10 ; compare i with 10

jge SHORT $LN1@main ; if i >= 10, exit loop

mov ecx, DWORD PTR _i$[ebp] ; load i into ECX (argument for call)

push ecx ; push argument onto stack

call _printing_function ; call printing_function

add esp, 4 ; clean up stack (remove argument)

jmp SHORT $LN2@main ; jump back to increment part

$LN1@main: ; loop exit point

xor eax, eax ; set return value to 0

mov esp, ebp ; restore ESP

pop ebp ; restore EBP (standard epilogue)

ret 0 ; return

_main ENDP

There is nothing particularly strange; I have marked the important parts in the code.

GCC 4.4.1 produces almost the same code, with only a small difference:

main proc near

var_20 = dword ptr -20h

var_4 = dword ptr -4

push ebp ; save EBP

mov ebp, esp ; set up stack frame

and esp, 0FFFFFFF0h ; align stack to 16-byte boundary

sub esp, 20h ; allocate local space

mov [esp+20h+var_4], 2 ; initialization: i = 2

jmp short loc_8048476 ; jump to condition check

loc_8048465:

mov eax, [esp+20h+var_4] ; load i

mov [esp+20h+var_20], eax ; pass i as argument

call printing_function ; call function

add [esp+20h+var_4], 1 ; i++

loc_8048476:

cmp [esp+20h+var_4], 9 ; compare i with 9

jle short loc_8048465 ; if i <= 9, continue loop

mov eax, 0 ; return value 0

leave ; restore stack frame

retn ; return

main endp

_main PROC

push esi ; save ESI (callee-saved)

mov esi, 2 ; i = 2 (using register)

$LL3@main:

push esi ; push i as argument

call _printing_function ; call function

inc esi ; i++

add esp, 4 ; clean up stack

cmp esi, 10 ; compare i with 10

jl SHORT $LL3@main ; if i < 10, continue loop

xor eax, eax ; return value 0

pop esi ; restore ESI

ret 0 ; return

_main ENDP

Now let us see what happens when we enable optimization (/Ox):

What happened here is slightly different: no stack space was allocated for the variable i, and the ESI register was used exclusively for it. This is possible in small functions with few local variables.

Another very important point: the printing_function() function must not change the value of ESI. The compiler is confident of this. If the compiler decided to use ESI inside printing_function(), it would have to save its value at the beginning and restore it at the end, as we saw with PUSH ESI / POP ESI.

Let us try GCC 4.4.1 with maximum optimization (-O3):

main proc near

var_10 = dword ptr -10h

push ebp ; save EBP

mov ebp, esp ; set up frame

and esp, 0FFFFFFF0h ; align stack

sub esp, 10h ; allocate space

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 2 ; pass 2

call printing_function ; call with 2

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 3 ; pass 3

call printing_function ; call with 3

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 4 ; pass 4

call printing_function ; call with 4

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 5 ; pass 5

call printing_function ; call with 5

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 6 ; pass 6

call printing_function ; call with 6

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 7 ; pass 7

call printing_function ; call with 7

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 8 ; pass 8

call printing_function ; call with 8

mov [esp+10h+var_10], 9 ; pass 9

call printing_function ; call with 9

xor eax, eax ; return 0

leave ; restore frame

retn ; return

main endp

Here the situation changed: the loop was completely unrolled (loop unrolling). This has the advantage of saving execution time by removing loop control instructions, but at the cost of larger code size.

Large fully unrolled loops are not recommended nowadays because large functions require more instruction cache space.

Let us increase the upper limit of i to 100 and try again.

GCC produces:

public main

main proc near

var_20 = dword ptr -20h

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

and esp, 0FFFFFFF0h

push ebx ; save EBX

mov ebx, 2 ; i = 2

sub esp, 1Ch

nop ; alignment

loc_80484D0:

mov [esp+20h+var_20], ebx ; pass i as argument

add ebx, 1 ; i++

call printing_function ; call function

cmp ebx, 64h ; i == 100?

jnz short loc_80484D0 ; continue loop if not

add esp, 1Ch

xor eax, eax ; return 0

pop ebx ; restore EBX

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

retn

main endp

This is very similar to what MSVC 2010 produces with optimization, except the EBX register is used as the counter i. GCC is confident that the register will not be changed inside printing_function(); otherwise it would save and restore it at the function entry/exit, as happened here in main().

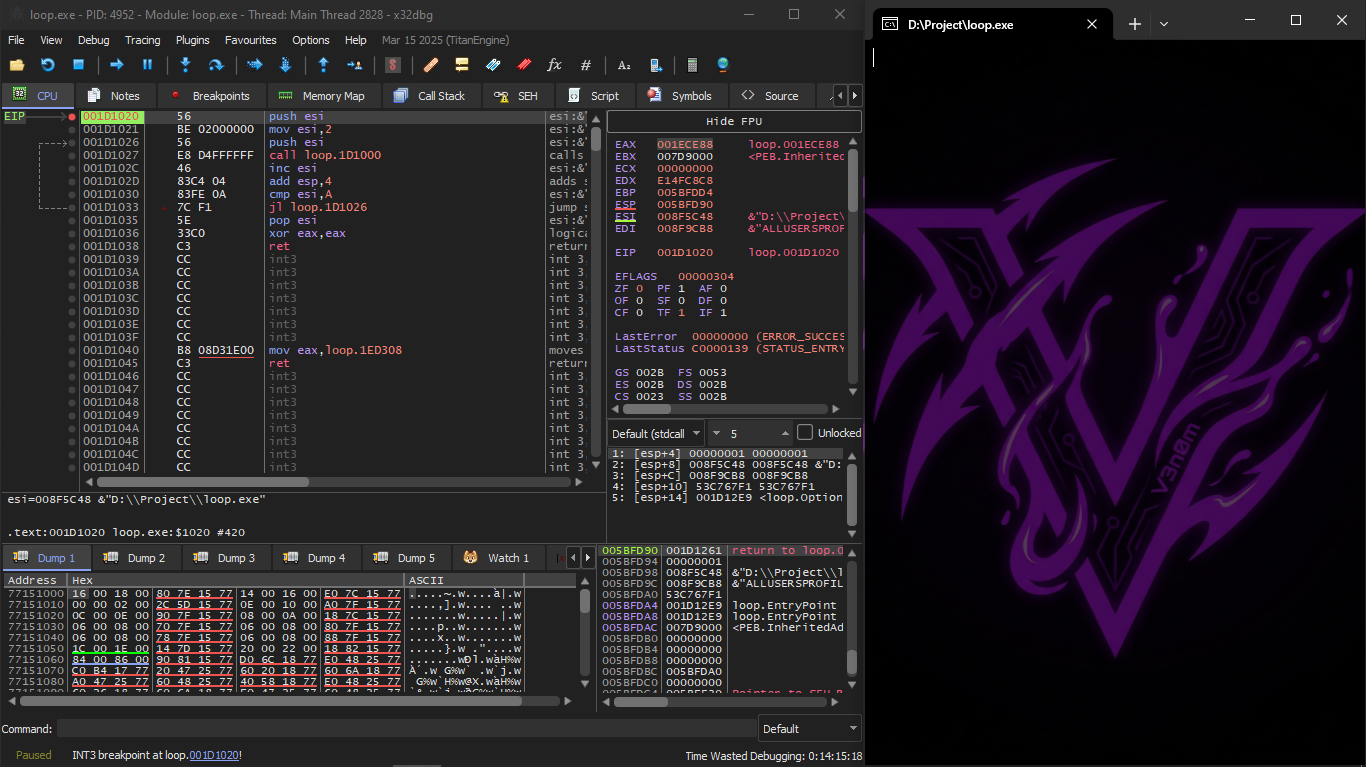

x86: x32dbg

The author also used OllyDbg, but we will run this example in x32dbg as well.

We start by compiling the C code with the command:

cl /Ox /Ob0 /W3 /Fe:loop.exe test.c

We load the resulting EXE into x32dbg and go to main:

At this point it is clear that x32dbg has detected the loop and shows the arrow on the right.

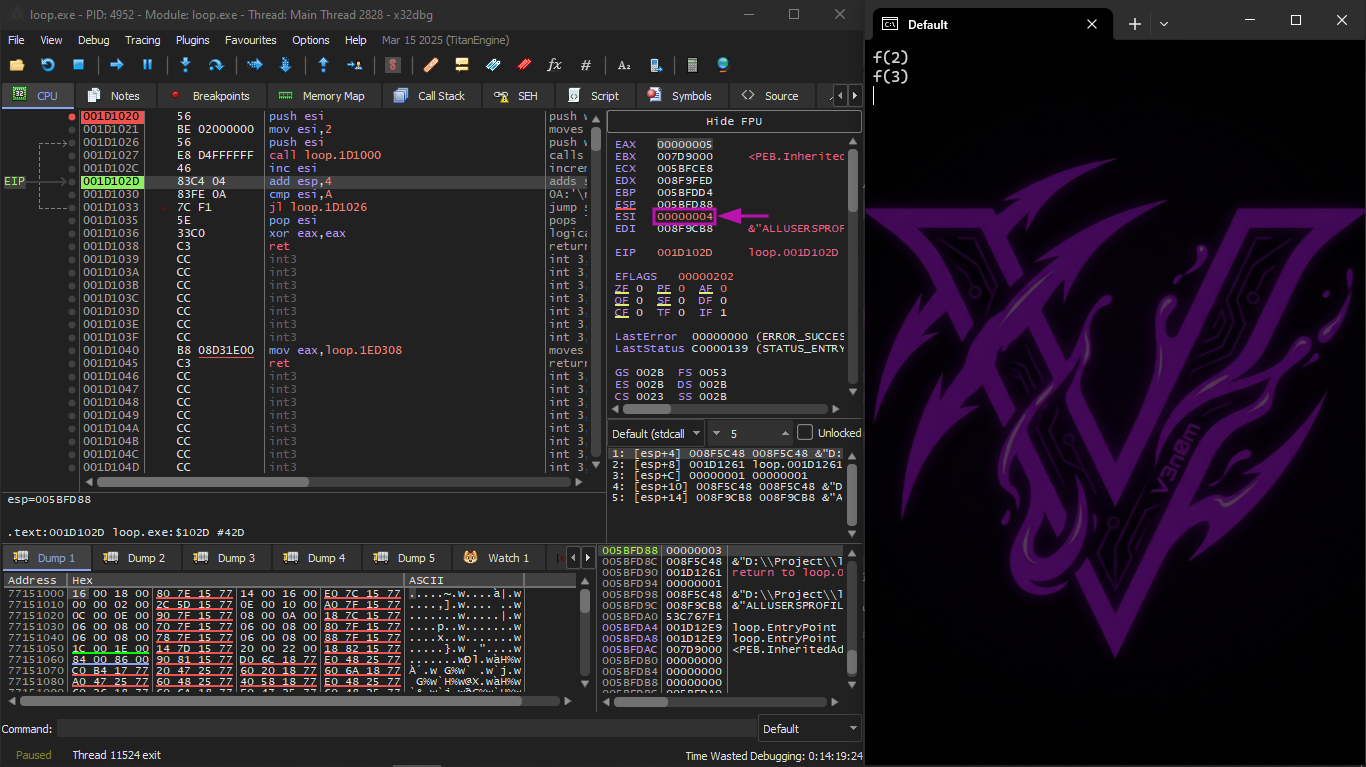

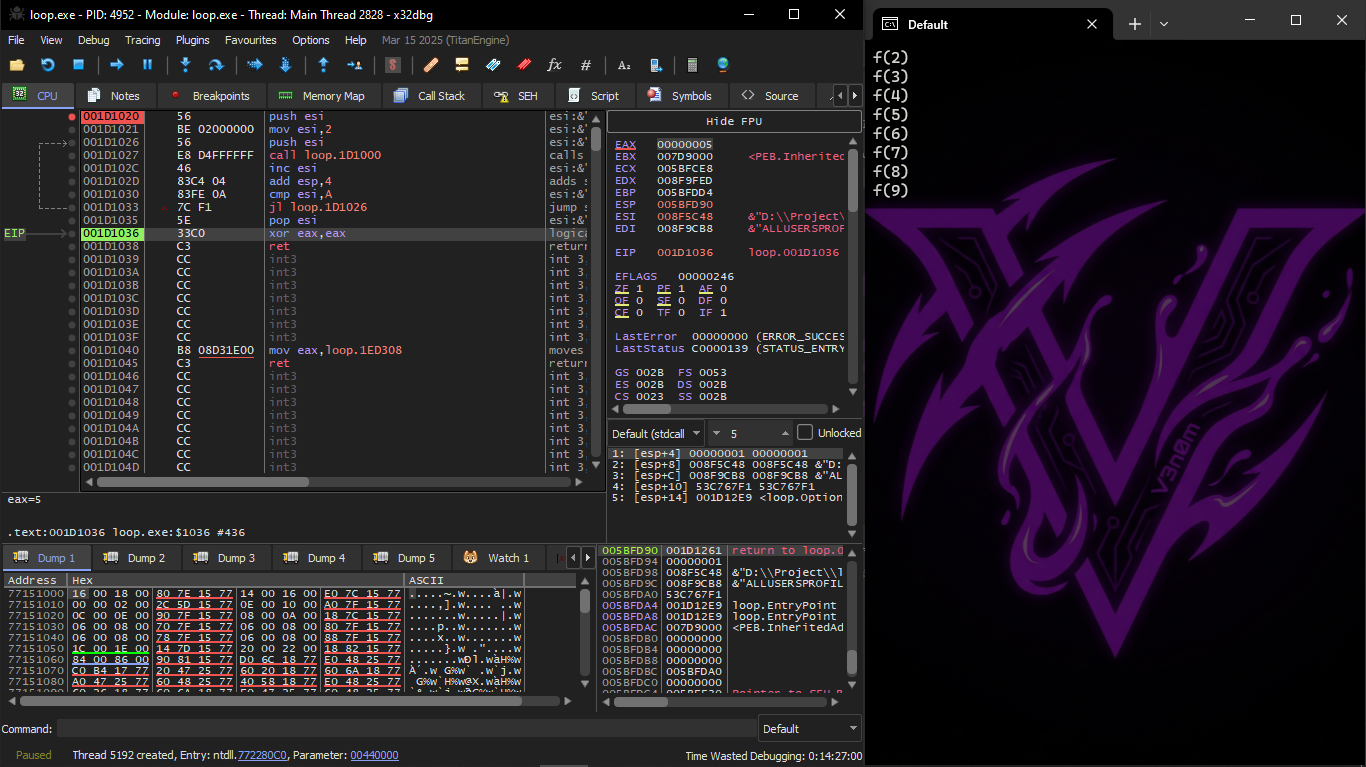

We start pressing F8 (Step Over) and notice that ESI increases by one each time:

The last value the loop takes is 9, so after the increment the JL instruction is not executed and the function finishes:

x86: tracer

The author said that manually tracing inside a debugger is not very convenient, so we will try using tracer.

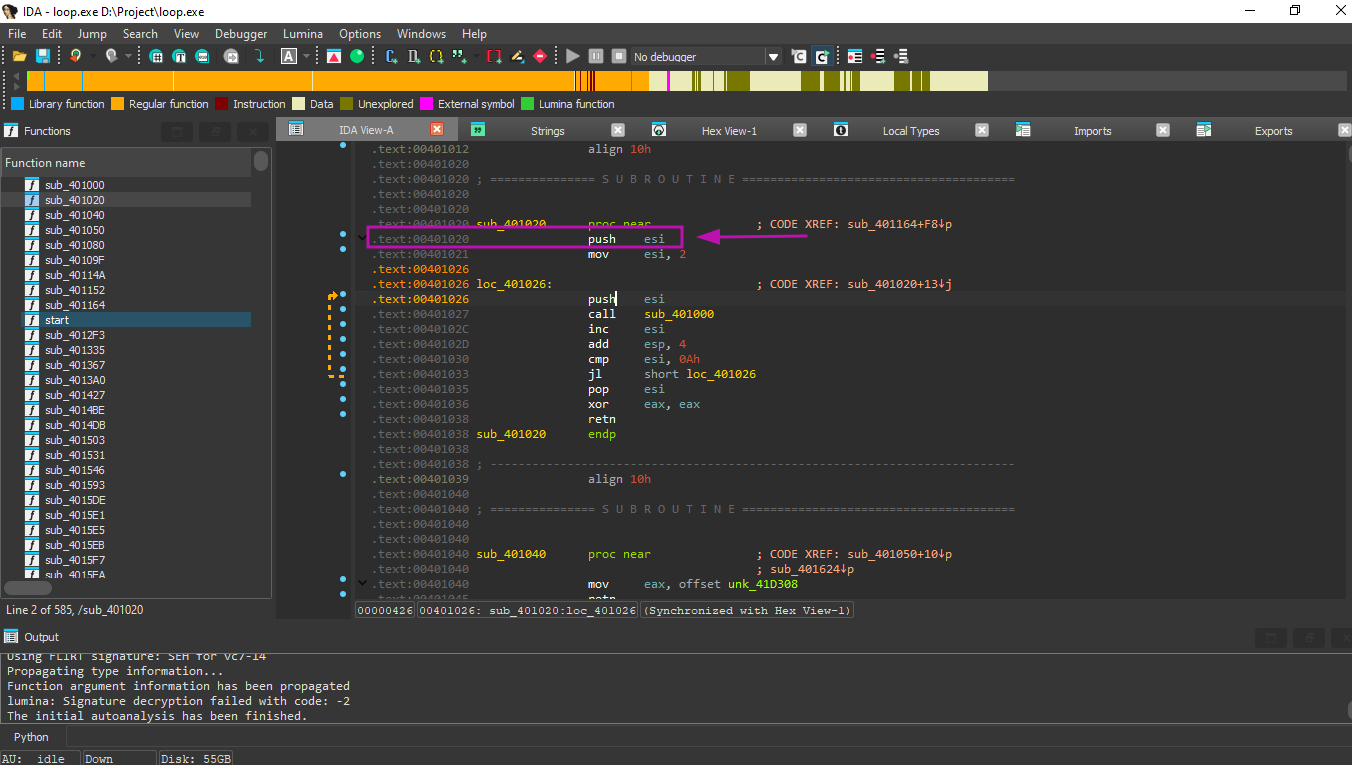

First, we open the example in IDA and find the address of the PUSH ESI instruction (which passes the only argument to printing_function()):

The address in this case is 0x401026.

We then run tracer (link to the tool used in the book: https://yurichev.com/tracer-en.html):

PS D:\Project> ./tracer.exe -l:loop.exe bpx=loop.exe!0x00401026

The -bpx option sets a breakpoint only at that address, and tracer then prints the register state.

In the tracer.log file we see:

Warning: no tracer.cfg file.

PID=18080|New process loop.exe

Warning: unknown (to us) INT3 breakpoint at ntdll.dll!LdrInitShimEngineDynamic+0x6e2 (0x77201ba2)

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x0022ce88 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x00000000 EDX=0xc3de76bb

ESI=0x00000002 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=PF IF

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x00000005 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x0020fe30 EDX=0x007b9415

ESI=0x00000003 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=CF PF AF SF IF

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x00000005 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x0020fe30 EDX=0x007b9415

ESI=0x00000004 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=CF PF AF SF IF

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x00000005 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x0020fe30 EDX=0x007b9415

ESI=0x00000005 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=CF AF SF IF

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x00000005 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x0020fe30 EDX=0x007b9415

ESI=0x00000006 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=CF PF AF SF IF

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x00000005 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x0020fe30 EDX=0x007b9415

ESI=0x00000007 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=CF AF SF IF

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x00000005 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x0020fe30 EDX=0x007b9415

ESI=0x00000008 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=CF AF SF IF

(0) loop.exe!0x401026

EAX=0x00000005 EBX=0x004c7000 ECX=0x0020fe30 EDX=0x007b9415

ESI=0x00000009 EDI=0x007ba678 EBP=0x0020ff1c ESP=0x0020fed4

EIP=0x00211026

FLAGS=CF PF AF SF IF

PID=18080|Process loop.exe exited. ExitCode=0 (0x0)

We can see that the value of the ESI register changes from 2 to 9.

Moreover, tracer can collect register values for all addresses inside the function—this is called a trace.

It then generates an IDA .idc script that adds comments.

Since we know in IDA that the address of the main() function is 0x00401020, we run:

PS D:\Project> .\tracer.exe -l:loop.exe bpf=loop.exe!0x00401020,trace:cc

BPF means: set a breakpoint on the entire function.

As a result, two scripts are produced:

loops_2.exe.idc

loops_2.exe_clear.idc

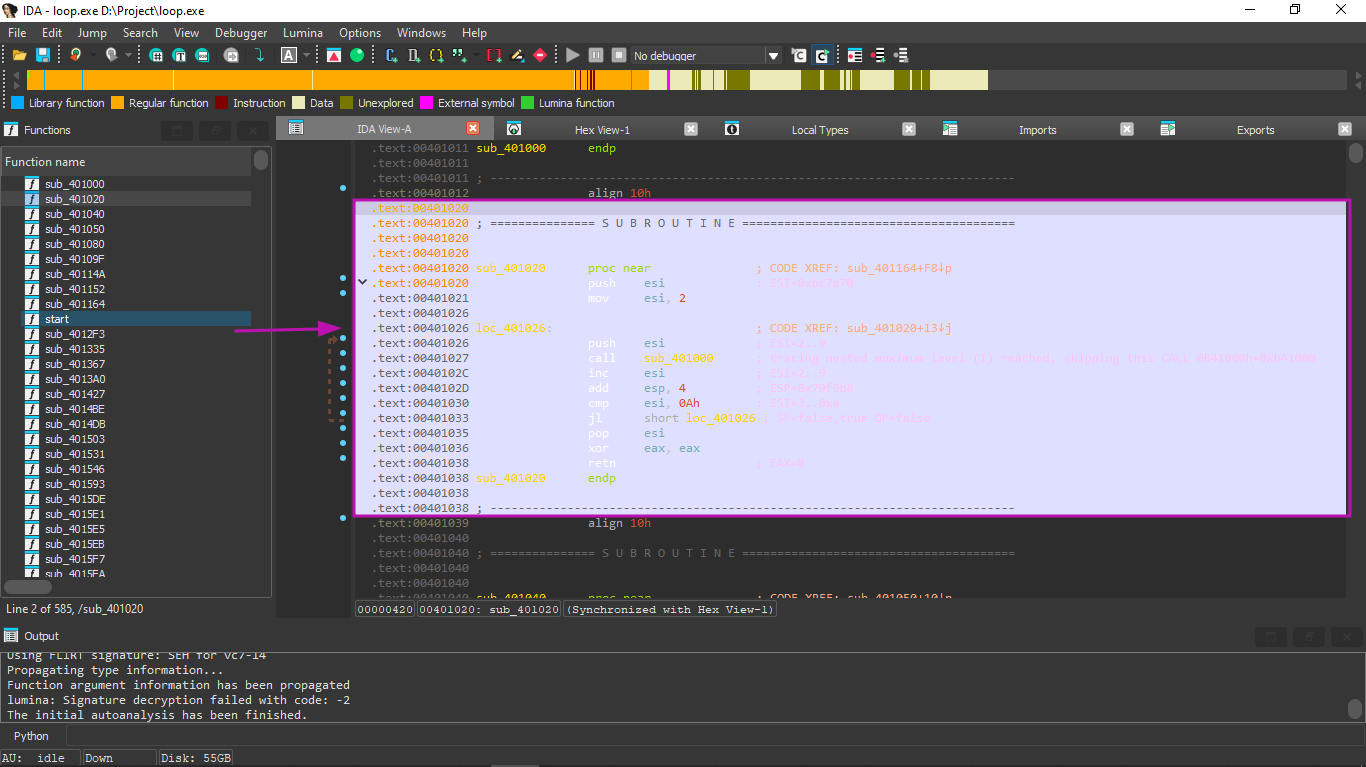

We load loops_2.exe.idc into IDA and see:

We notice that ESI can be from 2 to 9 at the start of the loop body, but after the increment it becomes from 3 to 0xA (10).

We also see that main() finishes with EAX = 0. Tracer also produces a file loops_2.exe.txt.

This file contains information about the number of times each instruction was executed and register values:

0x401020 (BASE+0x1020), e= 1 [PUSH ESI] ESI=0xbc7d70

0x401021 (BASE+0x1021), e= 1 [MOV ESI, 2]

0x401026 (BASE+0x1026), e= 8 [PUSH ESI] ESI=2..9

0x401027 (BASE+0x1027), e= 8 [CALL 0B41000h] tracing nested maximum level (1) reached, skipping this CALL 0B41000h=0xb41000

0x40102c (BASE+0x102c), e= 8 [INC ESI] ESI=2..9

0x40102d (BASE+0x102d), e= 8 [ADD ESP, 4] ESP=0x79f9b8

0x401030 (BASE+0x1030), e= 8 [CMP ESI, 0Ah] ESI=3..0xa

0x401033 (BASE+0x1033), e= 8 [JL 0B41026h] SF=false,true OF=false

0x401035 (BASE+0x1035), e= 1 [POP ESI]

0x401036 (BASE+0x1036), e= 1 [XOR EAX, EAX]

0x401038 (BASE+0x1038), e= 1 [RETN] EAX=0

Here we can use grep, etc.

ARM

Keil 6/2013: ARM mode (no optimization)

main

STMFD SP!, {R4,LR} ; save R4 and link register

MOV R4, #2 ; i = 2

B loc_368 ; jump to condition check

loc_35C ; CODE XREF: main+1C

MOV R0, R4 ; prepare argument (i)

BL printing_function ; call printing_function

ADD R4, R4, #1 ; i++

loc_368 ; CODE XREF: main+8

CMP R4, #0xA ; compare i with 10

BLT loc_35C ; if i < 10, continue loop

MOV R0, #0 ; return value 0

LDMFD SP!, {R4,PC} ; restore R4 and return

Here the loop counter i is stored in R4. The MOV R4, #2 instruction only performs the initialization of i.

The instructions MOV R0, R4 and BL printing_function form the loop body: the first prepares the argument for printing_function(), the second calls it.

The ADD R4, R4, #1 instruction increments i at each iteration.

The CMP R4, #0xA instruction compares i with 10 (0xA).

The following BLT (Branch Less Than) instruction jumps if i is less than 10.

Otherwise, 0 is written to R0 (return value) and execution finishes.

Optimizing Keil 6/2013: Thumb mode

_main

PUSH {R4,LR} ; save R4 and LR

MOVS R4, #2 ; i = 2

loc_132 ; CODE XREF: _main+E

MOVS R0, R4 ; prepare argument

BL printing_function ; call function

ADDS R4, R4, #1 ; i++

CMP R4, #0xA ; compare i with 10

BLT loc_132 ; if i < 10, continue

MOVS R0, #0 ; return value 0

POP {R4,PC} ; restore R4 and return

Same as before, no difference.

Optimizing Xcode 4.6.3 (LLVM): Thumb-2 mode

_main

PUSH {R4,R7,LR}

MOVW R4, #0x1124 ; address of format string "%d\n"

MOVS R1, #2

MOVT.W R4, #0

ADD R7, SP, #4

ADD R4, PC ; R4 = effective address of string

MOV R0, R4

BLX _printf ; print 2

MOV R0, R4

MOVS R1, #3

BLX _printf ; print 3

MOV R0, R4

MOVS R1, #4

BLX _printf ; print 4

MOV R0, R4

MOVS R1, #5

BLX _printf ; print 5

MOV R0, R4

MOVS R1, #6

BLX _printf ; print 6

MOV R0, R4

MOVS R1, #7

BLX _printf ; print 7

MOV R0, R4

MOVS R1, #8

BLX _printf ; print 8

MOV R0, R4

MOVS R1, #9

BLX _printf ; print 9

MOVS R0, #0

POP {R4,R7,PC}

In fact, this was the content of the printing_function() in my case:

void printing_function(int i)

{

printf ("%d\n", i);

};

So LLVM not only unrolled the loop, but also inlined the simple printing_function(), placing its body 8 times instead of calling it. This is possible when the function is very simple and called a small number of times (as here).

ARM64: Optimizing GCC 4.9.1

printing_function:

mov w1, w0 ; move argument to W1

adrp x0, .LC0 ; load page address of string

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC0 ; add low 12 bits offset

b printf ; jump to printf

main:

stp x29, x30, [sp, -32]! ; save frame pointer and link register

add x29, sp, 0 ; set frame pointer

str x19, [sp,16] ; save X19 (callee-saved)

mov w19, 2 ; i = 2 (using callee-saved X19)

.L3:

mov w0, w19 ; prepare argument

add w19, w19, 1 ; i++

bl printing_function ; call function

cmp w19, 10 ; compare i with 10

bne .L3 ; if i != 10, continue loop

mov w0, 0 ; return value 0

ldr x19, [sp,16] ; restore X19

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 32 ; restore FP/LR and deallocate

ret ; return

.LC0:

.string "f(%d)\n"

ARM64: Non-optimizing GCC 4.9.1

.LC0:

.string "f(%d)\n"

printing_function:

stp x29, x30, [sp, -32]! ; save FP and LR

add x29, sp, 0 ; set frame pointer

str w0, [x29,28] ; store argument on stack

adrp x0, .LC0 ; load string page

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC0 ; add offset

ldr w1, [x29,28] ; load argument

bl printf ; call printf

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 32 ; restore and deallocate

ret ; return

main:

stp x29, x30, [sp, -32]! ; save FP and LR

add x29, sp, 0 ; set frame pointer

mov w0, 2 ; load 2

str w0, [x29,28] ; store i = 2

b .L3 ; jump to condition check

.L4:

ldr w0, [x29,28] ; load i

bl printing_function ; call function

ldr w0, [x29,28] ; load i

add w0, w0, 1 ; i++

str w0, [x29,28] ; store new i

.L3:

ldr w0, [x29,28] ; load i

cmp w0, 9 ; compare i with 9

ble .L4 ; if i <= 9, continue loop

mov w0, 0 ; return 0

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 32 ; restore and deallocate

ret ; return

MIPS

Listing 1.176: Non-optimizing GCC 4.4.5 (IDA)

main:

addiu $sp, -0x28 ; allocate stack frame (40 bytes)

sw $ra, 0x28-4($sp) ; save return address

sw $fp, 0x28-8($sp) ; save frame pointer

move $fp, $sp ; set frame pointer

li $v0, 2 ; load immediate 2 into $v0

sw $v0, 0x28-0x10($fp) ; store i = 2

b loc_9C ; jump to condition check

or $at, $zero ; NOP (delay slot)

loc_80:

lw $a0, 0x28-0x10($fp) ; load i into $a0 (argument)

jal printing_function ; call printing_function

or $at, $zero ; NOP (delay slot)

lw $v0, 0x28-0x10($fp) ; load i

addiu $v0, 1 ; i++

sw $v0, 0x28-0x10($fp) ; store new i

loc_9C:

lw $v0, 0x28-0x10($fp) ; load i

slti $v0, 0xA ; set $v0 to 1 if i < 10

bnez $v0, loc_80 ; if true, continue loop

or $at, $zero ; NOP (delay slot)

move $v0, $zero ; return value 0

move $sp, $fp ; restore stack pointer

lw $ra, 0x28-4($sp) ; restore return address

lw $fp, 0x28-8($sp) ; restore frame pointer

addiu $sp, 0x28 ; deallocate stack frame

jr $ra ; return

or $at, $zero ; NOP (delay slot)

The only difference here is the new b instruction, which is generally a pseudo-instruction for BEQ.

Final note

In the generated code we notice that after initializing i, the loop body is not executed immediately—the condition is checked first, and only then the loop body may execute. This is correct, because if the condition is not met from the beginning, the loop body should not execute at all.

For example:

for (i=0; i<total_entries_to_process; i++)

loop_body;

Therefore the condition is checked before execution. However, with optimization the compiler may rearrange the order of condition check and loop body if it is sure that this case cannot occur (as in our simple example, and with compilers like Keil, Xcode (LLVM), MSVC with optimization).

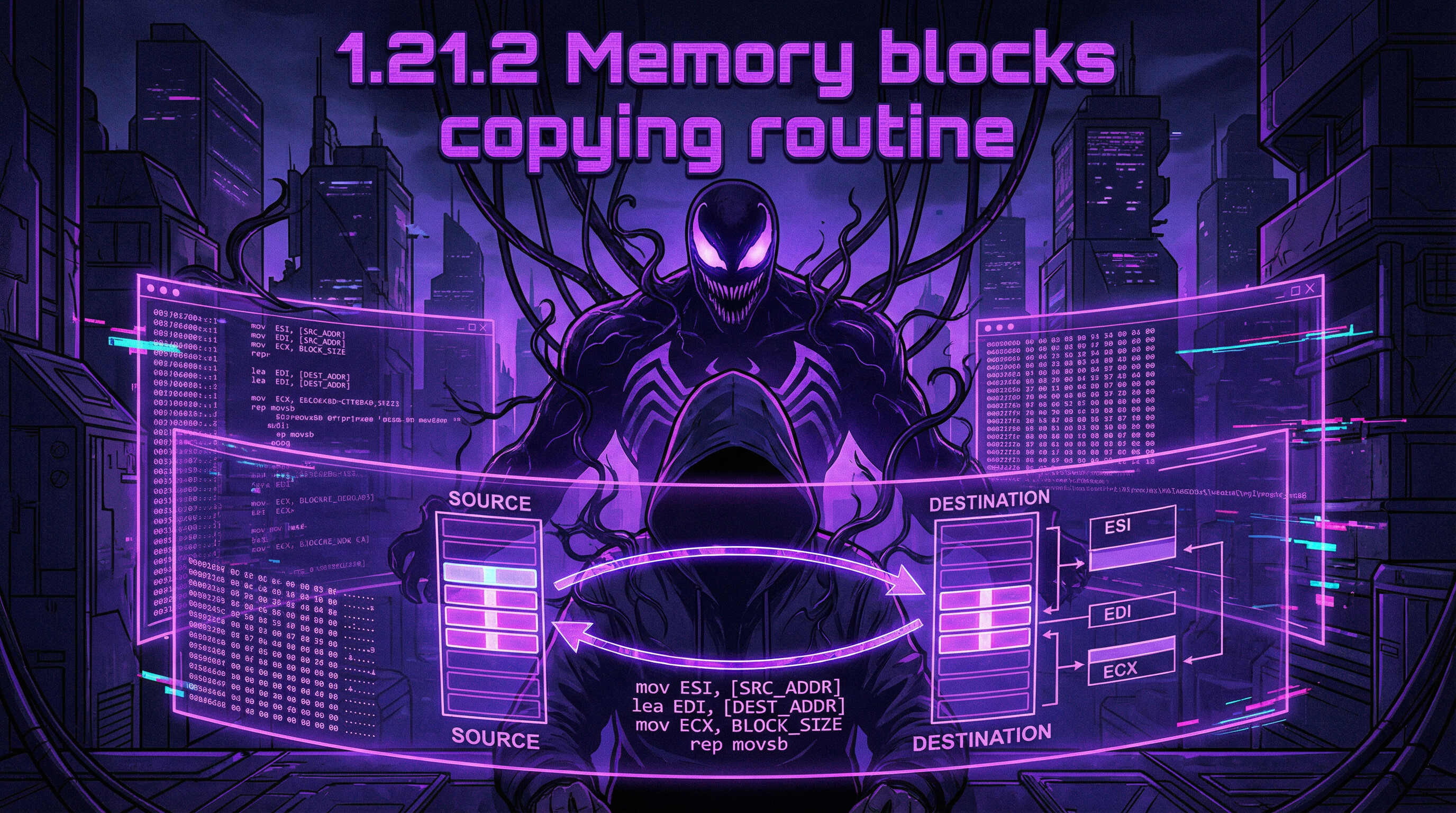

1.21.2 Memory blocks copying routine

In real-world practice, memory copy routines often copy 4 or 8 bytes per iteration and may use SIMD, vectorization, and other advanced techniques.

To keep things simple, this example is the simplest possible form:

#include <stdio.h> // include standard I/O header

void my_memcpy (unsigned char* dst, unsigned char* src, size_t cnt) // define byte-by-byte memory copy function

{

size_t i; // declare counter i

for (i=0; i<cnt; i++) // loop from 0 to cnt-1

dst[i]=src[i]; // copy byte from source to destination

};

my_memcpy: ; Listing 1.177: GCC 4.9 x64 optimized for size (-Os)

; RDI = destination address

; RSI = source address

; RDX = block size

xor eax, eax ; initialize counter i to 0 (EAX = 0)

.L2:

cmp rax, rdx ; have all bytes been copied? if yes, exit

je .L5 ; jump to exit if done

mov cl, BYTE PTR [rsi+rax] ; load byte from source + i into CL

mov BYTE PTR [rdi+rax], cl ; store byte into destination + i

inc rax ; i++

jmp .L2 ; repeat loop

.L5:

ret ; return

my_memcpy: ; Listing 1.178: GCC 4.9 ARM64 optimized for size (-Os)

; X0 = destination address

; X1 = source address

; X2 = block size

mov x3, 0 ; initialize counter i to 0

.L2:

cmp x3, x2 ; are we done copying?

beq .L5 ; if yes, exit

ldrb w4, [x1,x3] ; load byte from source + i into W4

strb w4, [x0,x3] ; store byte into destination + i

add x3, x3, 1 ; i++

b .L2 ; repeat loop

.L5:

ret ; return

my_memcpy PROC ; Listing 1.179: Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (Thumb mode)

; R0 = destination address

; R1 = source address

; R2 = block size

PUSH {r4,lr} ; save R4 and LR

MOVS r3,#0 ; initialize counter i to 0

B |L0.12| ; jump to condition check (at end of loop)

|L0.6|

LDRB r4,[r1,r3] ; load byte from source + i into R4

STRB r4,[r0,r3] ; store byte into destination + i

ADDS r3,r3,#1 ; i++

|L0.12|

CMP r3,r2 ; i < size?

BCC |L0.6| ; if yes, continue loop

POP {r4,pc} ; restore R4 and return

ENDP

ARM – ARM mode

Keil in ARM mode fully exploits conditional suffixes.

my_memcpy PROC

; R0 = destination address

; R1 = source address

; R2 = block size

MOV r3,#0 ; initialize counter i to 0

|L0.4|

CMP r3,r2 ; have all bytes been copied?

LDRBCC r12,[r1,r3] ; load byte from source + i (conditional: only if i < size)

STRBCC r12,[r0,r3] ; store byte into destination + i (conditional)

ADDCC r3,r3,#1 ; i++ (conditional)

BCC |L0.4| ; jump back to loop start if i < size

BX lr ; return

ENDP

Thus there is only one jump instead of two.

MIPS

my_memcpy: ; Listing 1.181: GCC 4.4.5 optimized for size (-Os) (IDA)

b loc_14 ; jump to condition check

move $v0, $zero ; initialize counter i to 0 (delay slot)

loc_8: ; CODE XREF: my_memcpy+1C

lbu $v1, 0($t0) ; load unsigned byte from source address in $t0 into $v1

addiu $v0, 1 ; i++

sb $v1, 0($a3) ; store byte into destination address in $a3

loc_14: ; CODE XREF: my_memcpy

sltu $v1, $v0, $a2 ; set $v1 to 1 if i < cnt

addu $t0, $a1, $v0 ; compute source + i address

bnez $v1, loc_8 ; if i < cnt, continue loop

addu $a3, $a0, $v0 ; compute destination + i address (delay slot)

jr $ra ; return

or $at, $zero ; NOP (delay slot)

Here are some instructions:

- LBU: Load Byte Unsigned (zero-extends the rest of the bits)

- LB: Load Byte with sign extension

- SB: Store Byte (lowest 8 bits)

Like ARM, all MIPS registers are 32-bit, so even when working with a single byte, a full 32-bit register must be used.

Vectorization

An optimized GCC version can do much more with this example, which will be explained later.

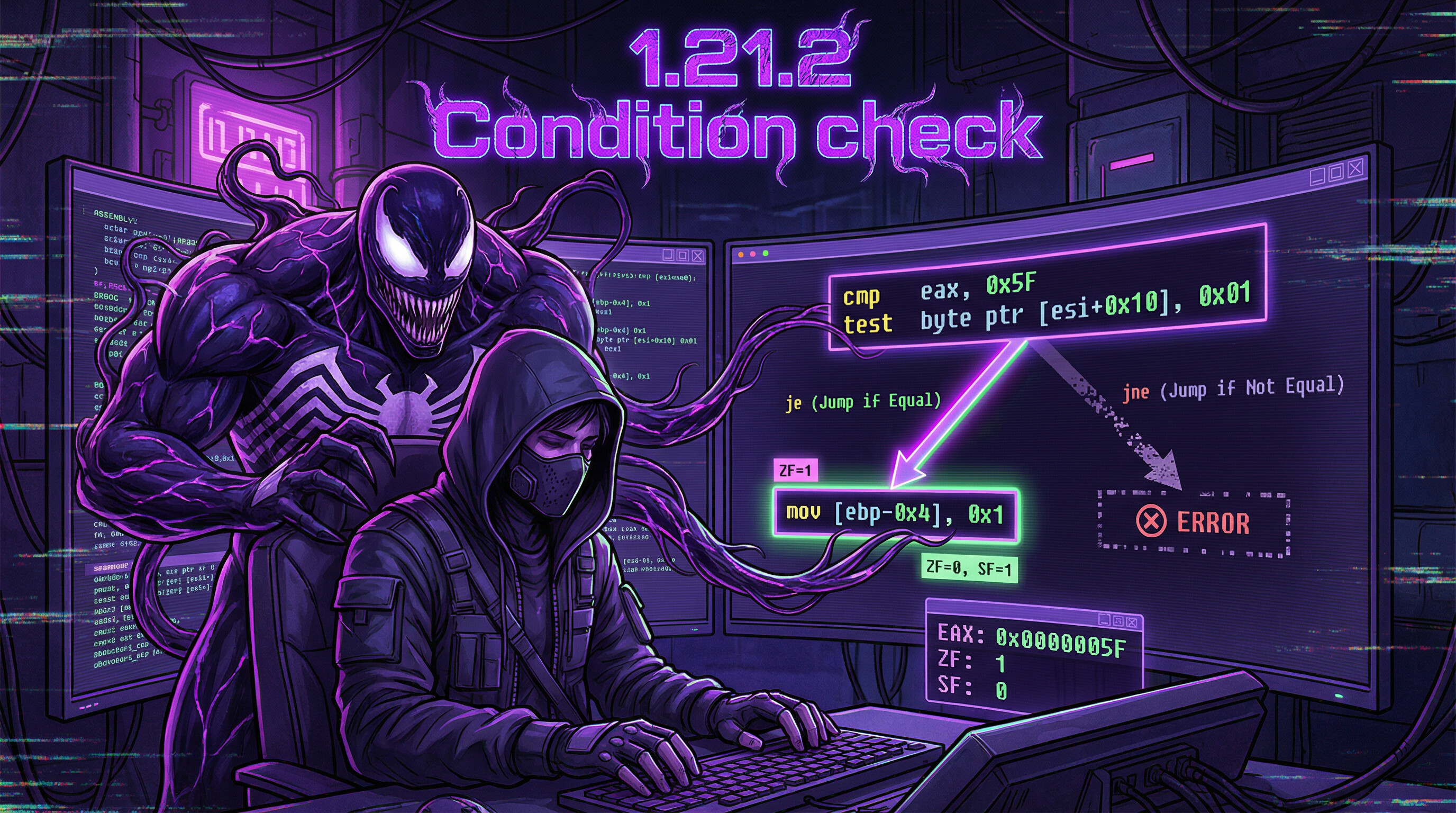

1.21.3 Condition check

The author explained that it is very important to remember that in the for() construct, the condition is not checked at the end, but at the beginning before the loop body executes. However, in many cases it is easier for the compiler to check the condition at the end after the loop body, sometimes adding an extra check at the beginning.

An example of this:

#include <stdio.h>

void f(int start, int finish)

{

for (; start<finish; start++)

printf ("%d\n", start);

};

GCC 5.4.0 x64 – Optimized

f:

cmp edi, esi ; condition check (1)

jge .L9 ; if start >= finish, exit

push rbp

push rbx

mov ebp, esi ; save finish

mov ebx, edi ; save start

sub rsp, 8

.L5:

mov edx, ebx ; prepare argument (current value)

xor eax, eax

mov esi, OFFSET FLAT:.LC0 ; "%d\n"

mov edi, 1

add ebx, 1 ; increment current value

call __printf_chk ; print

cmp ebp, ebx ; condition check (2)

jne .L5 ; continue if current != finish

add rsp, 8

pop rbx

pop rbp

.L9:

rep ret ; return

Here we see two condition checks.

Hex-Rays (at least version 2.2.0) decompiles it as:

void __cdecl f(unsigned int start, unsigned int finish)

{

unsigned int v2; // ebx@2

__int64 v3; // rdx@3

if ( (signed int)start < (signed int)finish )

{

v2 = start;

do

{

v3 = v2++;

_printf_chk(1LL, "%d\n", v3);

}

while ( finish != v2 );

}

}

In this case, we can confidently replace the do/while() with for() and also remove the first condition check.

1.22.4 Conclusion

General skeleton for a loop from 2 to 9 inclusive:

Listing 1.182: x86

mov [counter], 2 ; initialization

jmp check ; jump to condition check

body:

; loop body

; do whatever you want here

; use the counter variable from the stack

add [counter], 1 ; increment

check:

cmp [counter], 9 ; compare with 9

jle body ; if <= 9, continue loop

The increment can be done with 3 instructions in non-optimized code:

Listing 1.183: x86

MOV [counter], 2 ; initialization

JMP check

body:

; loop body

; do whatever you want here

; use the counter variable from the stack

MOV REG, [counter] ; increment

INC REG

MOV [counter], REG

check:

CMP [counter], 9

JLE body

If the loop body is small, we can dedicate a full register to the counter:

Listing 1.184: x86

MOV EBX, 2 ; initialization

JMP check

body:

; loop body

; do whatever you want here

; use the counter in EBX, but do not modify it!

INC EBX ; increment

check:

CMP EBX, 9

JLE body

Sometimes the compiler changes the order of loop parts:

Listing 1.185: x86

MOV [counter], 2 ; initialization

JMP label_check

label_increment:

ADD [counter], 1 ; increment

label_check:

CMP [counter], 10

JGE exit

; loop body

; do whatever you want here

; use the counter variable from the stack

JMP label_increment

exit:

Usually the condition is checked before the loop body, but the compiler may reverse it and place it after the loop body. This happens when the compiler is sure the condition is true on the first iteration, meaning the loop body must execute at least once.

Listing 1.186: x86

MOV REG, 2 ; initialization

body:

; loop body

; do whatever you want here

; use the counter in REG, but do not modify it!

INC REG ; increment

CMP REG, 10

JL body

Using the LOOP instruction

This is very rare, and compilers do not use it.

If you see it, the code is most likely hand-written by a human, not a compiler.

Listing 1.187: x86

; counting down from 10 to 1

MOV ECX, 10

body:

; loop body

; do whatever you want here

; use the counter in ECX, but do not modify it!

LOOP body

ARM

In this example, register R4 is dedicated to the counter:

Listing 1.188: ARM

MOV R4, 2 ; initialization

B check

body:

; loop body

; do whatever you want here

; use the counter in R4, but do not modify it!

ADD R4, R4, #1 ; increment

check:

CMP R4, #10

BLT body