Reverse Engineering for Beginners : switch()/case/default {Part1}

1.22.1 Small number of cases

x86: Non-optimizing MSVC

This function with a small number of cases in switch() will look like this:

The author began explaining that when dealing with a switch() with a small number of cases, it is impossible to determine whether the source code actually contained a switch() or just several if() statements chained together.

This means that switch() is merely syntactic sugar for a large number of nested if() statements.

There is nothing particularly new in the generated code, except that the compiler copied the value of variable a to a temporary local variable named tv64. If we compile this with GCC 4.4.1, even with maximum optimization (-O3), the result will be very similar.

Optimizing MSVC

Now let us enable optimization in MSVC using /Ox:

Let us simply explain what happened here:

First:

The value of a is placed in the EAX register, then:

This looks strange, but the goal is to test whether the value is zero.

- If the result is zero → ZF flag is set

- Then the

JE(Jump if Equal or JZ) instruction works - And we jump directly to label

$LN4@f - And "zero" is printed

If the jump did not occur:

- Subtract 1

- Then subtract 1 again

- As soon as the result becomes zero → the appropriate jump occurs

If no jump occurred, print "something unknown".

Second:

We see that the string address is placed in the variable a itself, then printf() is called with JMP instead of CALL.

Why?

- The caller of function

f()did:CALL f- This pushed the return address (RA) onto the stack

- While

f()is executing, the stack layout is:- ESP → return address

- ESP+4 → variable a

- When calling

printf():- We need exactly the same stack layout

- But the difference is that the first argument should be the string address

This is what the code did:

- Replaced the value of

awith the string address - Jumped directly with

JMPtoprintf()

printf() prints the string and then executes RET, popping the return address from the stack and returning directly to the caller of f() without returning to f() itself. Thus f() is completely bypassed at the end. This technique is somewhat similar to the idea of longjmp(), and of course it is all done for speed.

We can summarize this a bit: if the last thing in a function is a call to another function with no code after it, the compiler can:

- Modify the arguments

- Jump with

JMP - And let

REThappen from the other function

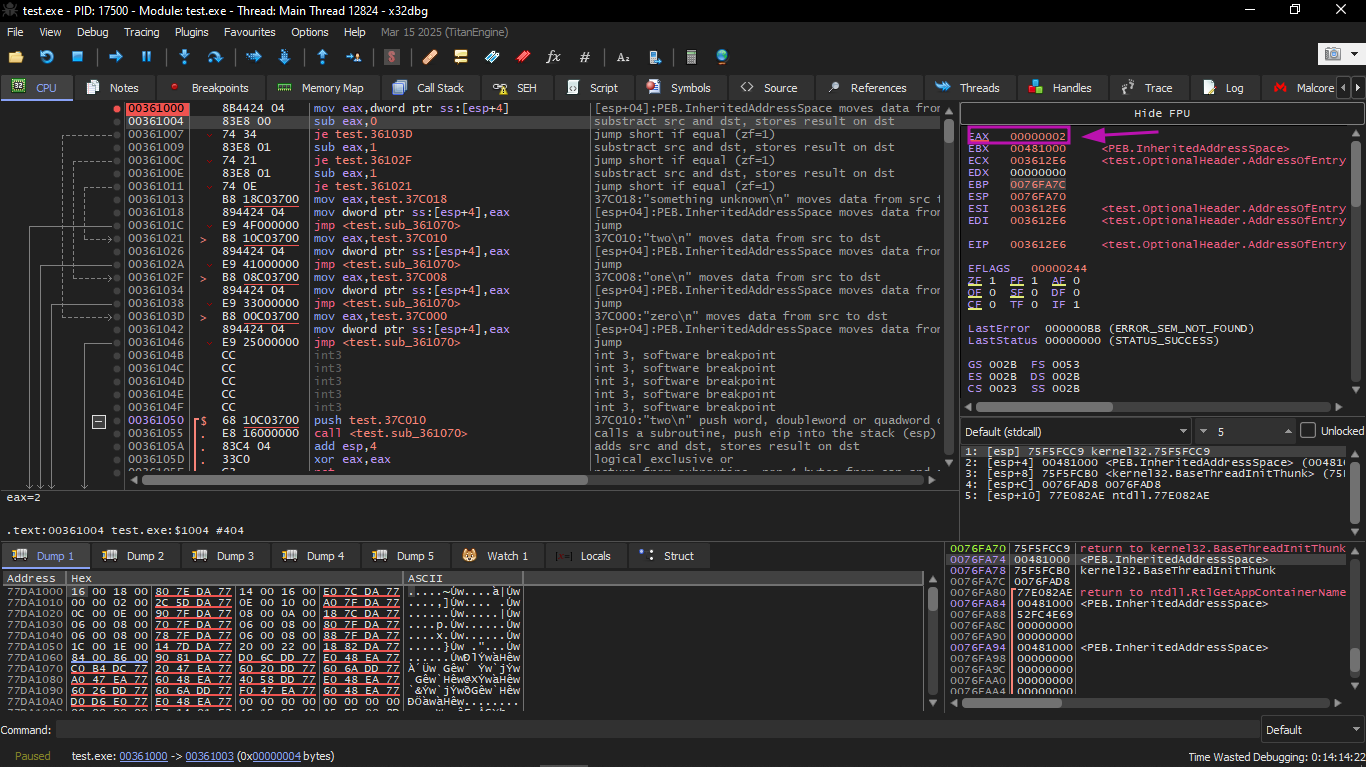

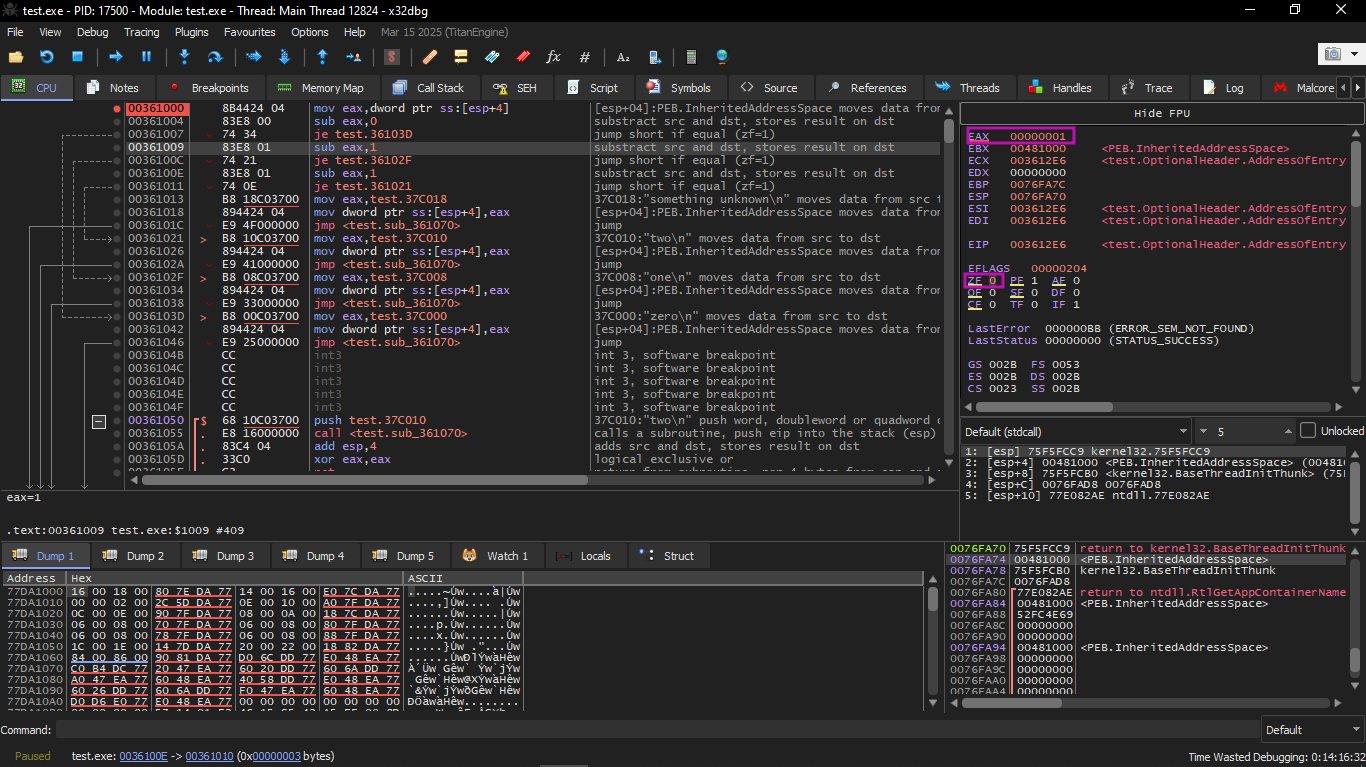

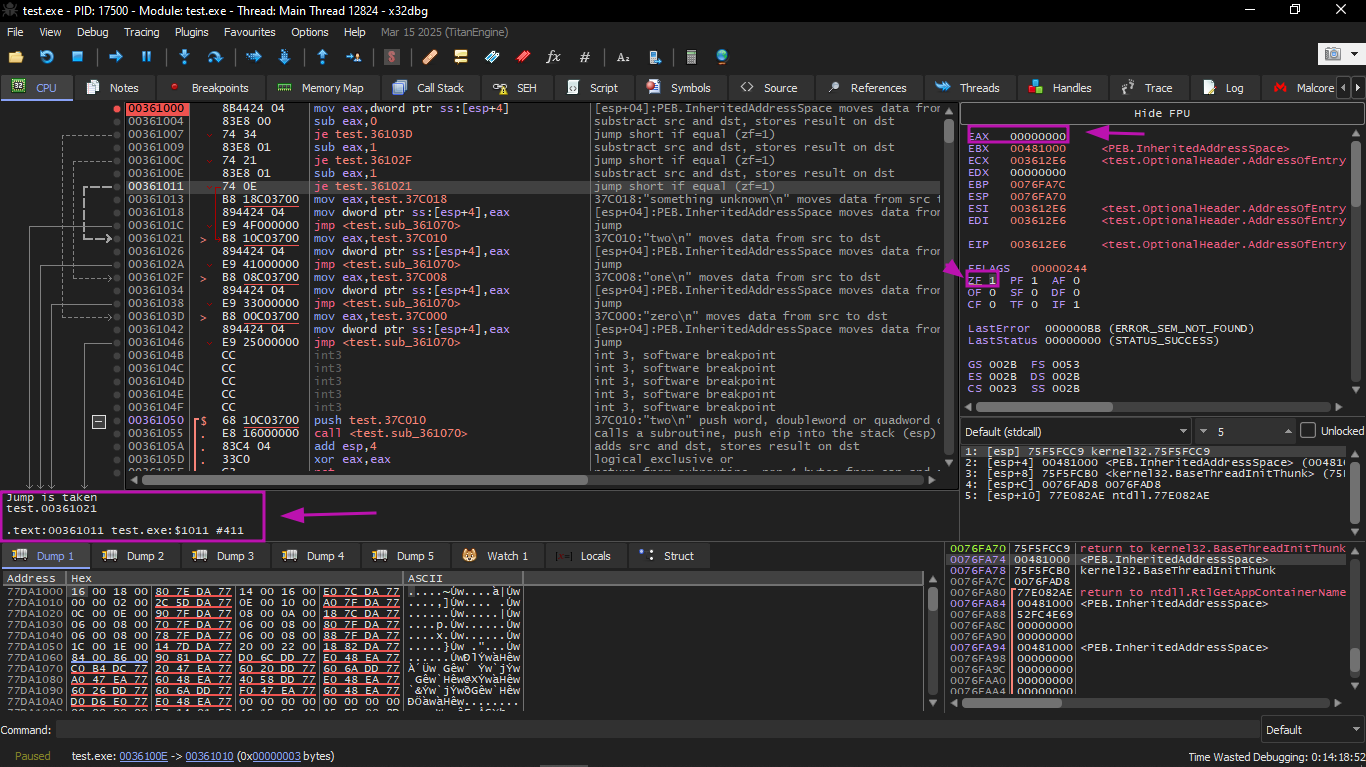

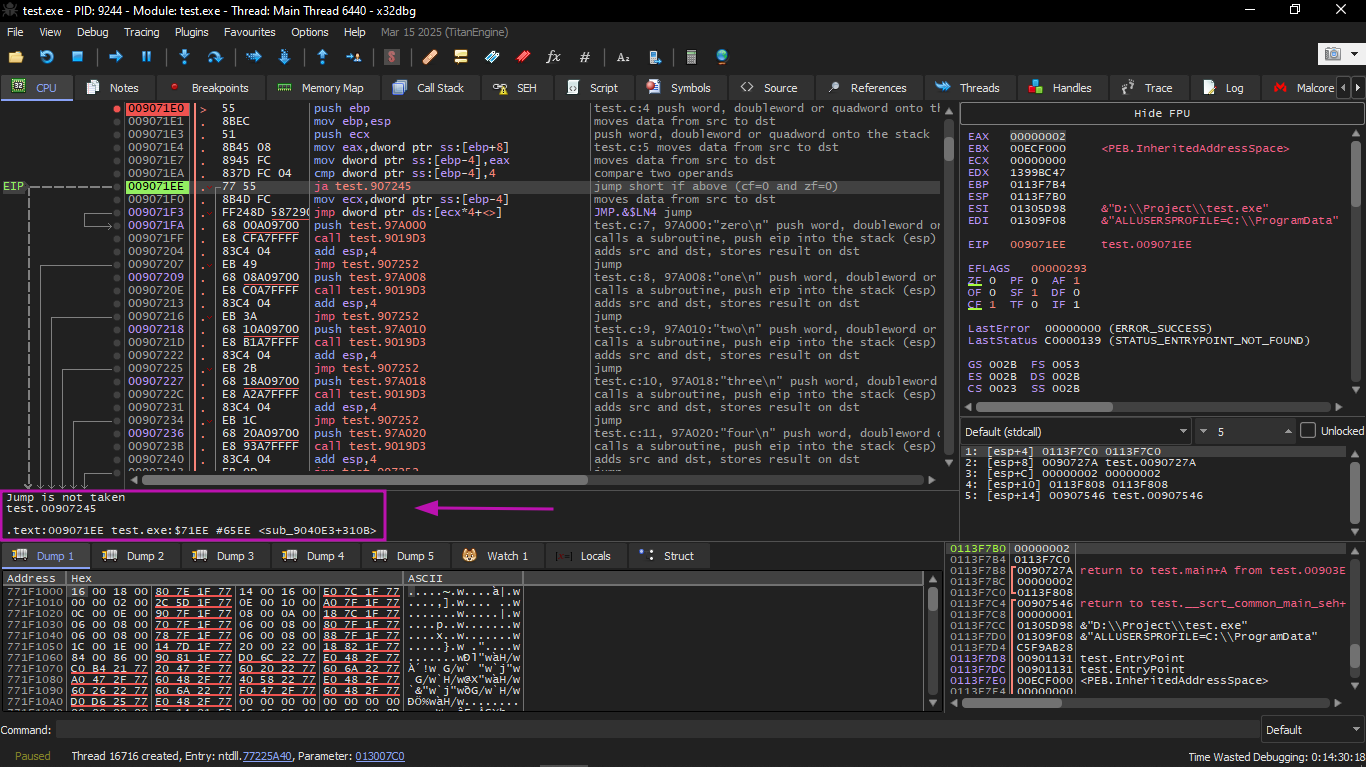

x32dbg (EX2)

Note: I could not get this example to work perfectly because the compiler is newer than the one in the book, which made a slight difference. I will try to explain the example as much as possible.

We run the same example in x32dbg after compiling and start running it in the debugger.

EAX value is 2 initially, which is the input value of the function.

0 is subtracted from 2 in EAX. Of course, EAX still has 2. But the ZF flag is now 0, meaning the result is not zero:

Then another SUB is performed. EAX finally becomes 0 and the ZF flag is set because the result became zero:

Now the current argument to the function is 2, and 2 is currently on the stack.

The pointer to the string is written, and then the jump occurs. This is the first instruction in printf() in MSVCR100.DLL.

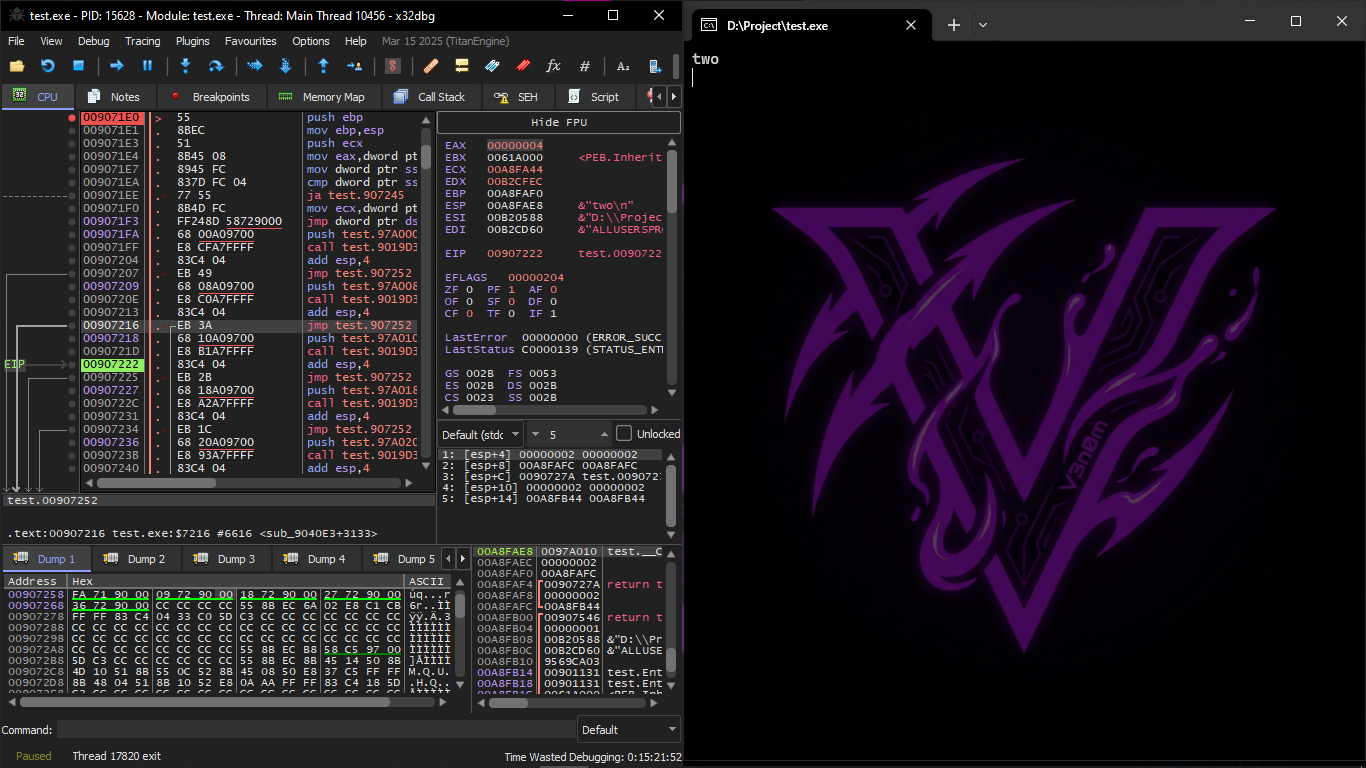

After that, printf() takes the string as the only argument and prints it. This is the last instruction in printf().

The string "two" is now printed on the console window.

And the jump was direct from inside printf() to main() because the RA on the stack does not point to a location in f(), but points to main().

ARM: Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (ARM mode)

Again, looking at this code we cannot determine whether it was a switch() or just several if statements.

In general, we see conditional instructions here (like ADREQ which means "Equal") which execute only if R0 = 0, and then load the address of the string "zero\n" into R0.

The following BEQ instruction transfers control to loc_170 if R0 = 0.

The question is: will BEQ work correctly since ADREQ just changed the value of R0 before it?

Yes, it will work because BEQ checks the flags set by the CMP instruction, and ADREQ does not change any flags at all.

The rest of the instructions are familiar to us. There is only one call to printf() at the end, and we have explained this trick before.

In the end, there are 3 paths leading to printf().

The last CMP R0, #2 instruction exists to check if a = 2. If not, the ADRNE instruction loads the pointer to the string "something unknown\n" into R0, since we are sure at this stage that the variable a is not equal to those numbers.

If R0 = 2, the pointer to the string "two\n" will be loaded into R0 via ADREQ.

ARM: Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (Thumb mode)

As mentioned before, it is not possible to add conditional predicates to most instructions in Thumb mode, so the Thumb code here is similar to CISC-style x86 code and is very easy to understand.

ARM64: Non-optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

The input value type is int, so the W0 register is used instead of the full X0 register.

String pointers are passed to puts() using the ADRP/ADD pair of instructions.

ARM64: Optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

More optimized code. The CBZ (Compare and Branch on Zero) instruction jumps if W0 is zero.

There is also a direct jump to puts() instead of calling it, as explained before.

MIPS

This function always ends with a call to puts(), so we see a direct jump to puts() (JR means Jump Register) instead of using "jump and link".

We also see many NOP instructions after LW instructions. This is called a load delay slot: another type of delay slot in MIPS.

The instruction after LW can execute simultaneously while LW is still loading the value from memory. But the instruction after that cannot use the result just loaded by LW.

Modern MIPS processors have a feature to stall if the next instruction uses the result of LW, so this issue is considered obsolete. But GCC still adds NOP instructions to support older MIPS processors.

1.22.2 A lot of cases

If the switch() statement has many cases, it is not convenient for the compiler to generate large code with many JE/JNE instructions.

x86: Non-optimizing MSVC

What we see here is a set of printf() calls with different arguments. Each not only has a memory address in the process, but also internal symbolic labels generated by the compiler. All these labels are also listed in an internal table named $LN11@f.

At the beginning of the function, if a is greater than 4, control flow is passed to label $LN1@f, where printf() is called with the argument "something unknown".

But if the value of a is less than or equal to 4, it is multiplied by 4 and added to the address of table $LN11@f. This forms an address inside the table that points exactly to the element we need.

For example, let us say a equals 2.

2 * 4 = 8 (each table element is an address in a 32-bit process, so each element is 4 bytes in size). The address of table $LN11@f + 8 is the table element that stores the label named $LN4@f. The JMP instruction fetches the address $LN4@f from the table and jumps there.

This table is sometimes called a jumptable or branch table.

Then the appropriate printf() is called with the argument "two".

Literally, the instruction:

means: jump to the DWORD stored at address $LN11@f + ecx * 4.

npad is a macro in assembly language that aligns the next label to a 4-byte (or 16-byte) boundary. This is very suitable for the processor because it can fetch 32-bit values from memory via the memory bus, cache memory, etc., more efficiently when they are aligned.

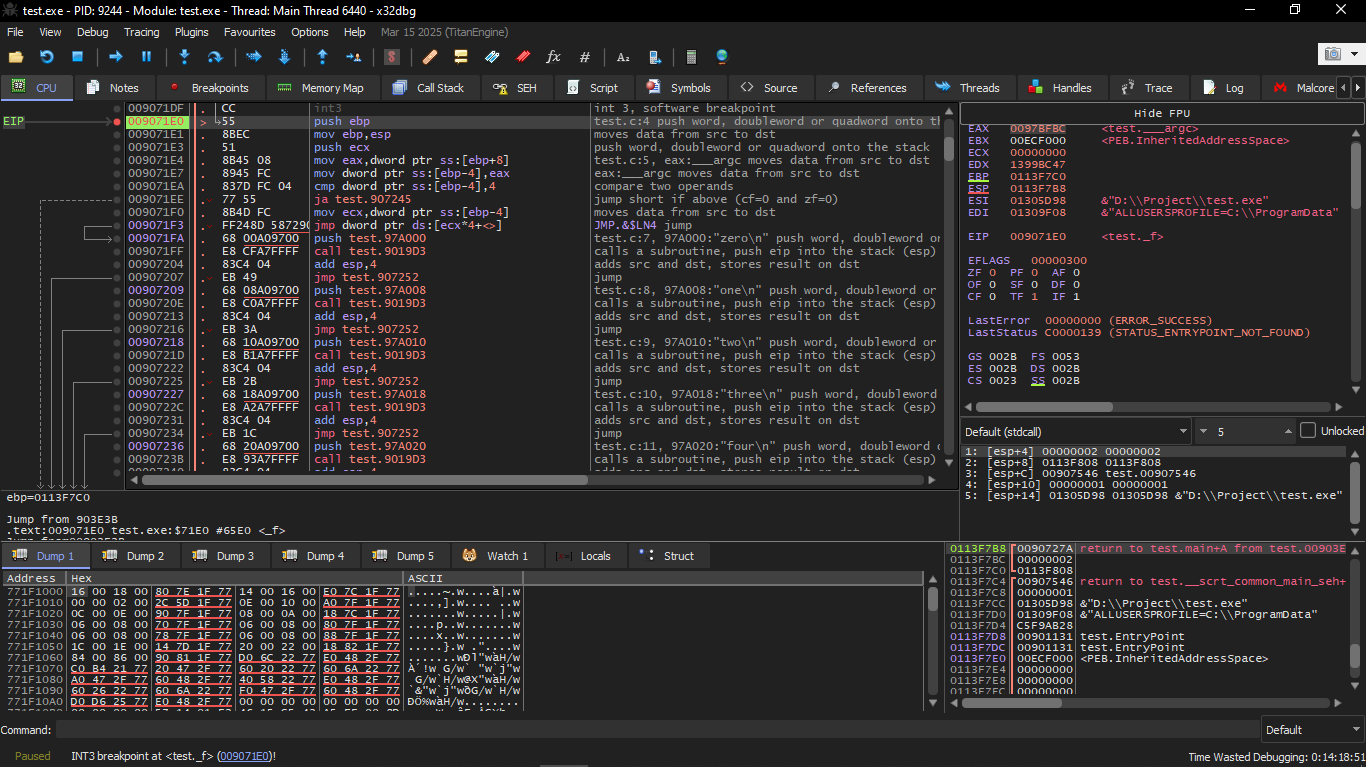

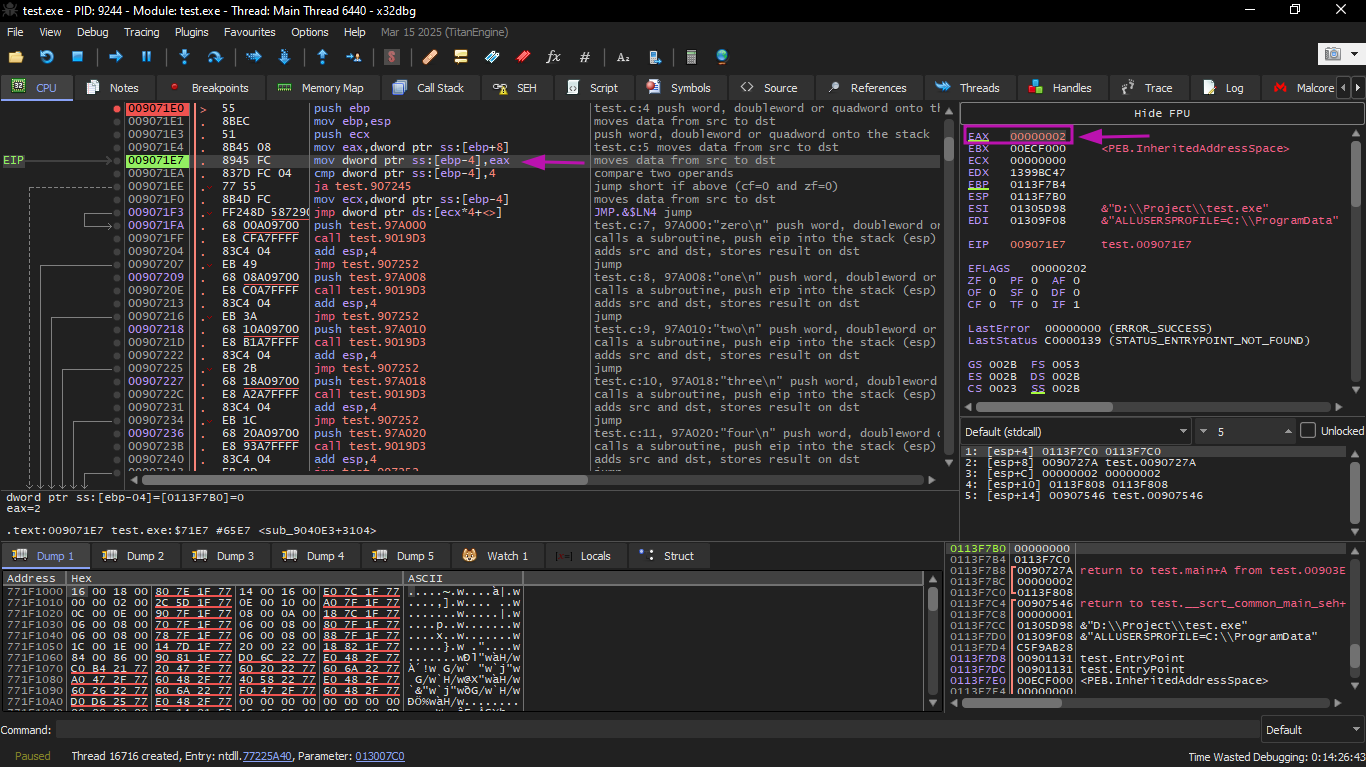

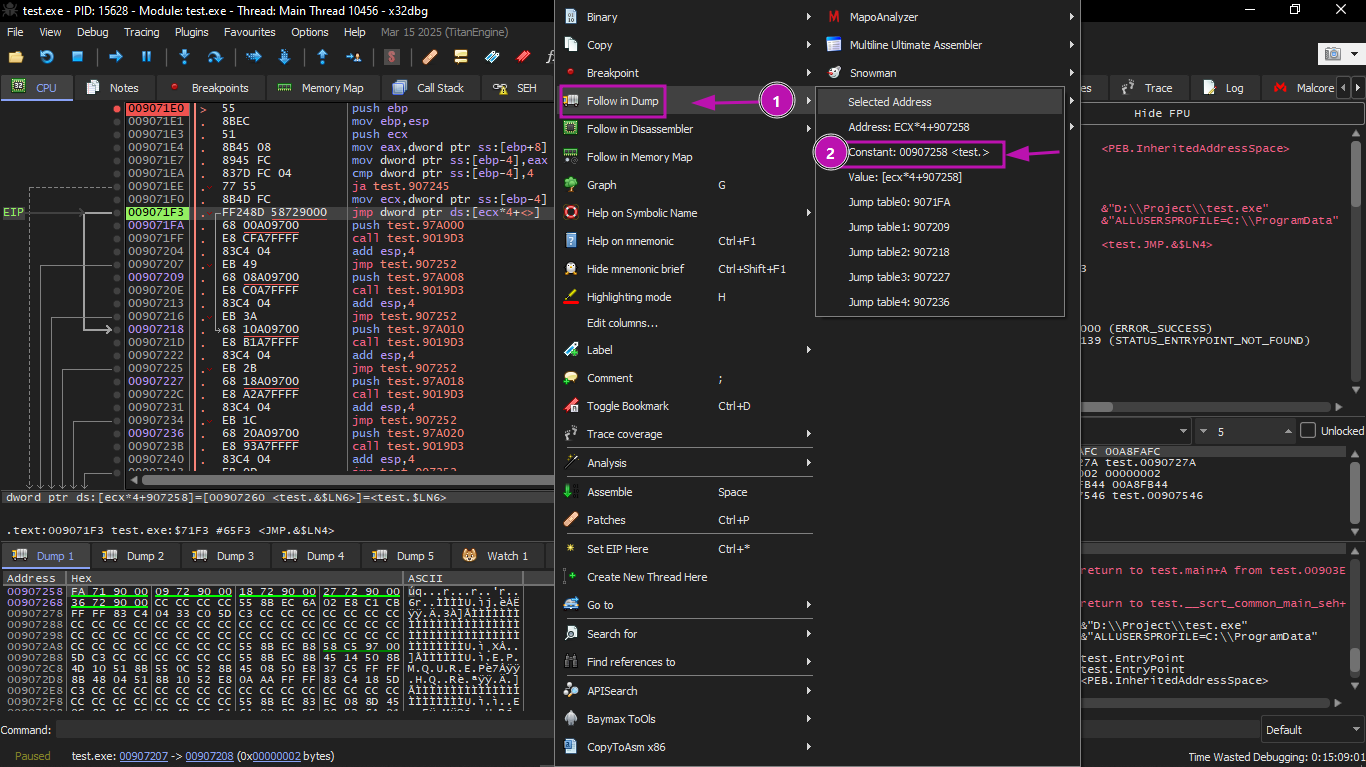

x32dbg

We run the same example in x32dbg after compiling and start running it in the debugger.

The input value of the function (2) is loaded into EAX:

Then the input value is checked: is it greater than 4? If not, the "default" jump is not taken:

Then we can view the jumptable by choosing Follow in Dump → Constant:

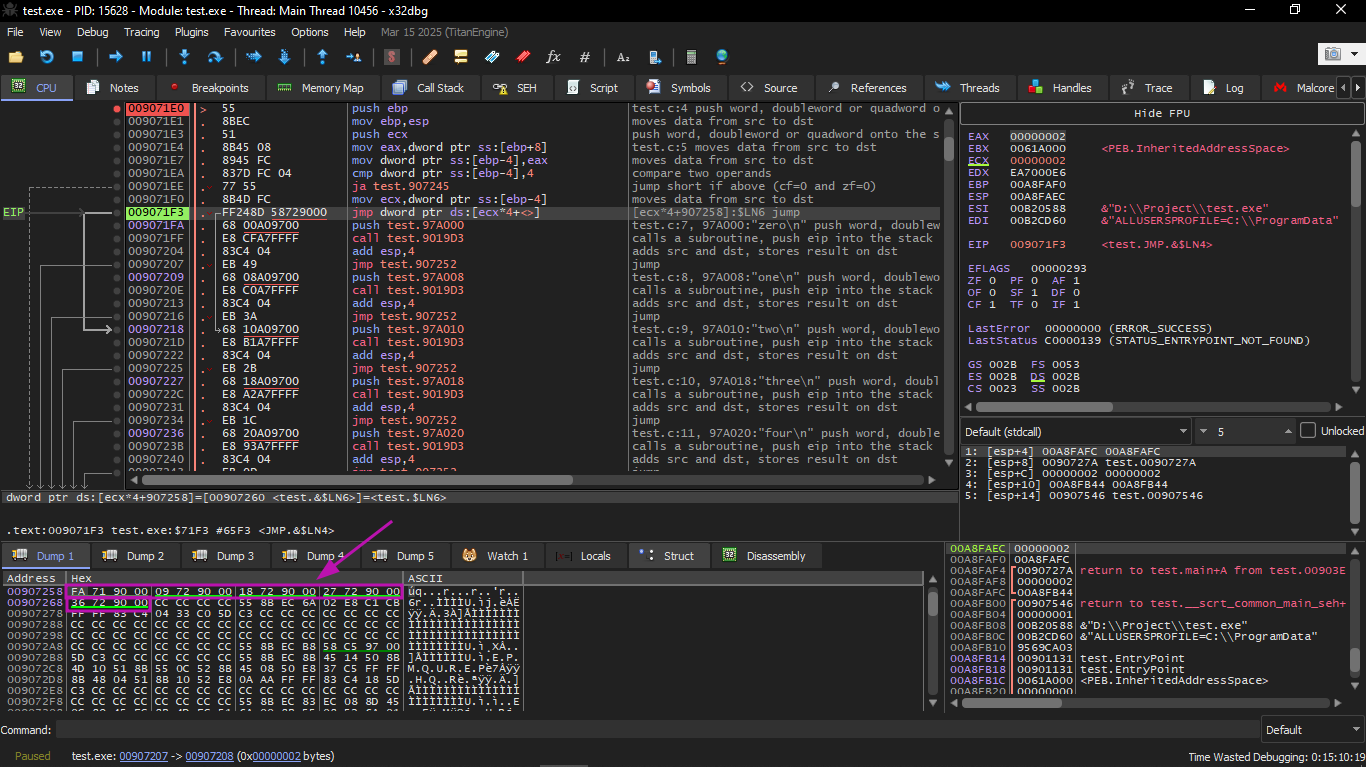

Now we see the jumptable in the data window. These are 5 32-bit values.

Now ECX is 2, so the third element (index 2) in the table will be used.

After the jump we are at 0x907218 — the code that prints "two" will now execute:

Non-optimizing GCC

Let us see what GCC 4.4.1 produces:

This is almost the same thing, with a small difference: the argument arg_0 is multiplied by 4 by shifting left by 2 bits (which is essentially the same as multiplying by 4), then the label address is taken from the array off_804855C, stored in EAX, and then JMP EAX performs the actual jump.

ARM: Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (ARM mode)

This code exploits the fact that all instructions in ARM mode are fixed size (4 bytes).

Recall that the maximum value of a is 4 and any larger value will cause the string "something unknown\n" to be printed.

The first instruction CMP R0, #5 compares the input value of a with 5.

The next instruction ADDCC PC, PC, R0,LSL#2 executes only if R0 < 5 (CC = Carry clear / Less than).

Thus, if ADDCC did not execute (i.e., R0 ≥ 5 case), a jump to label default_case occurs.

But if R0 < 5 and ADDCC executed, what happens is: the value of R0 is multiplied by 4. In fact, LSL#2 at the end of the instruction means "shift left by 2 bits". But as we will see later in the "Shifts" section, shift left by 2 bits equals multiplication by 4.

Then R0 * 4 is added to the current value in PC, thus jumping to one of the B (Branch) instructions below.

At the moment of executing ADDCC, the value of PC is 8 bytes (0x180) ahead of the address of the ADDCC instruction itself (0x178), or in other words, two instructions ahead.

This is how the pipeline works in ARM processors: when ADDCC is executed, the processor is already processing the instruction two steps ahead, so PC points there. This point must be memorized.

If a = 0, 0 is added to the PC value, and the actual PC value (which is 8 bytes ahead) is written to PC, resulting in a jump to label loc_180, which is 8 bytes ahead of where the ADDCC instruction is.

If a = 1: PC + 8 + a*4 = PC + 8 + 4 = PC + 12 = 0x184, which is the address of label loc_184.

With each increment of a, the resulting PC value increases by 4. And 4 is the length of an instruction in ARM mode, and also the length of each B instruction, of which there are 5 in a row.

Each of these five B instructions transfers control forward to what is programmed in the switch().

Loading the appropriate string pointer happens there, etc.

ARM: Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (Thumb mode)

It is not possible to be sure that all instructions in Thumb and Thumb-2 have the same size.

One could also say that in these modes instructions have variable length, like in x86.

Therefore, a special table is added containing information about the number of cases (excluding default-case) and also the offset for each case with the label to which control should go in the appropriate case.

There is a special function here to handle the table and transfer control, named __ARM_common_switch8_thumb. It starts with BX PC, whose purpose is to switch the processor to ARM mode.

Then the function responsible for handling the table is executed. It is too advanced to explain here now, so let us leave it.

Interestingly, the function uses the LR register as a pointer to the table.

Indeed, after calling this function, LR contains the address after the instruction BL __ARM_common_switch8_thumb, which is where the table starts.

It is also noteworthy that the code is generated as a separate reusable function, meaning the compiler does not emit the same code for each switch().

IDA successfully understood it as a service function and table, and added comments to the labels like: jumptable 000000FA case 0.

MIPS

The new instruction for us here is SLTIU ("Set on Less Than Immediate Unsigned"). It is the same as SLTU ("Set on Less Than Unsigned"), but the "I" means "immediate", i.e., a number is written directly in the instruction.

BNEZ means "Branch if Not Equal to Zero". The code is very close to other ISAs.

SLL ("Shift Word Left Logical") multiplies by 4. MIPS is ultimately a 32-bit CPU, so all addresses in the jumptable are 32-bit addresses.

Conclusion

The general structure of switch():

The jump to the address in the jump table can also be done using the instruction:

JMP jump_table[REG*4] or JMP jump_table[REG*8] in x64.

And the jumptable is just an array of pointers.