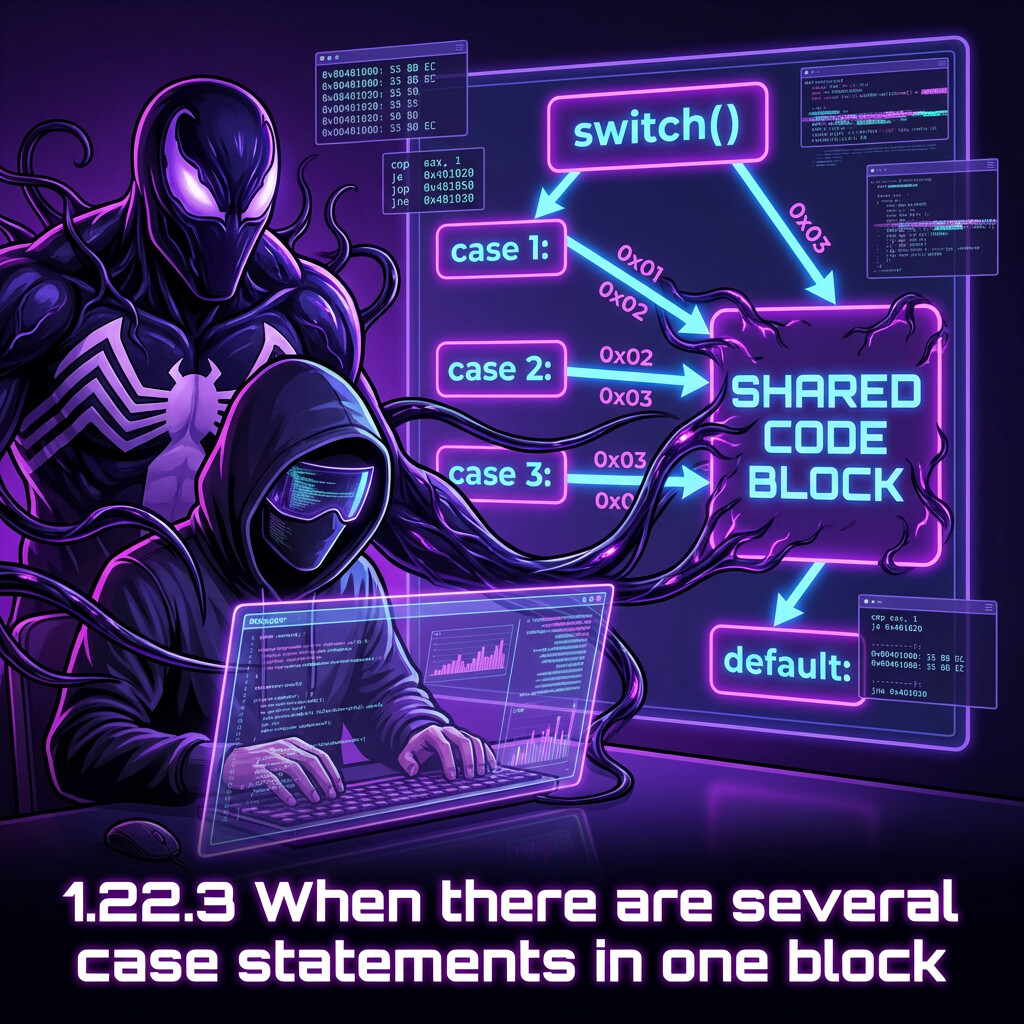

1.22.3 When there are several case statements in one block

This is a very popular construct: several case statements for the same block:

#include <stdio.h>

void f(int a)

{

switch (a)

{

case 1:

case 2:

case 7:

case 10:

printf ("1, 2, 7, 10\n");

break;

case 3:

case 4:

case 5:

case 6:

printf ("3, 4, 5\n");

break;

case 8:

case 9:

case 20:

case 21:

printf ("8, 9, 21\n");

break;

case 22:

printf ("22\n");

break;

default:

printf ("default\n");

break;

};

};

int main()

{

f(4);

};

The author said that it would be a huge waste to generate a block for each possible case, so usually what is done is to generate each block + some kind of dispatcher.

MSVC

$SG2798 DB '1, 2, 7, 10', 0aH, 00H

$SG2800 DB '3, 4, 5', 0aH, 00H

$SG2802 DB '8, 9, 21', 0aH, 00H

$SG2804 DB '22', 0aH, 00H

$SG2806 DB 'default', 0aH, 00H

_a$ = 8

_f PROC

mov eax, DWORD PTR _a$[esp-4] ; load input value

dec eax ; decrement (a -= 1)

cmp eax, 21 ; compare with 21

ja SHORT $LN1@f ; if > 21, jump to default

movzx eax, BYTE PTR $LN10@f[eax] ; load byte from index table (zero-extended)

jmp DWORD PTR $LN11@f[eax*4] ; jump using pointer table

$LN5@f: ; print '1, 2, 7, 10'

mov DWORD PTR _a$[esp-4], OFFSET $SG2798

jmp DWORD PTR __imp__printf

$LN4@f: ; print '3, 4, 5'

mov DWORD PTR _a$[esp-4], OFFSET $SG2800

jmp DWORD PTR __imp__printf

$LN3@f: ; print '8, 9, 21'

mov DWORD PTR _a$[esp-4], OFFSET $SG2802

jmp DWORD PTR __imp__printf

$LN2@f: ; print '22'

mov DWORD PTR _a$[esp-4], OFFSET $SG2804

jmp DWORD PTR __imp__printf

$LN1@f: ; default

mov DWORD PTR _a$[esp-4], OFFSET $SG2806

jmp DWORD PTR __imp__printf

npad 2 ; align table

$LN11@f:

DD $LN5@f ; pointer for index 0

DD $LN4@f ; index 1

DD $LN3@f ; index 2

DD $LN2@f ; index 3

DD $LN1@f ; index 4 (default)

$LN10@f:

DB 0 ; a=1

DB 0 ; a=2

DB 1 ; a=3

DB 1 ; a=4

DB 1 ; a=5

DB 1 ; a=6

DB 0 ; a=7

DB 2 ; a=8

DB 2 ; a=9

DB 0 ; a=10

DB 4 ; a=11 (default)

DB 4 ; a=12

DB 4 ; a=13

DB 4 ; a=14

DB 4 ; a=15

DB 4 ; a=16

DB 4 ; a=17

DB 4 ; a=18

DB 4 ; a=19

DB 2 ; a=20

DB 2 ; a=21

DB 3 ; a=22

_f ENDP

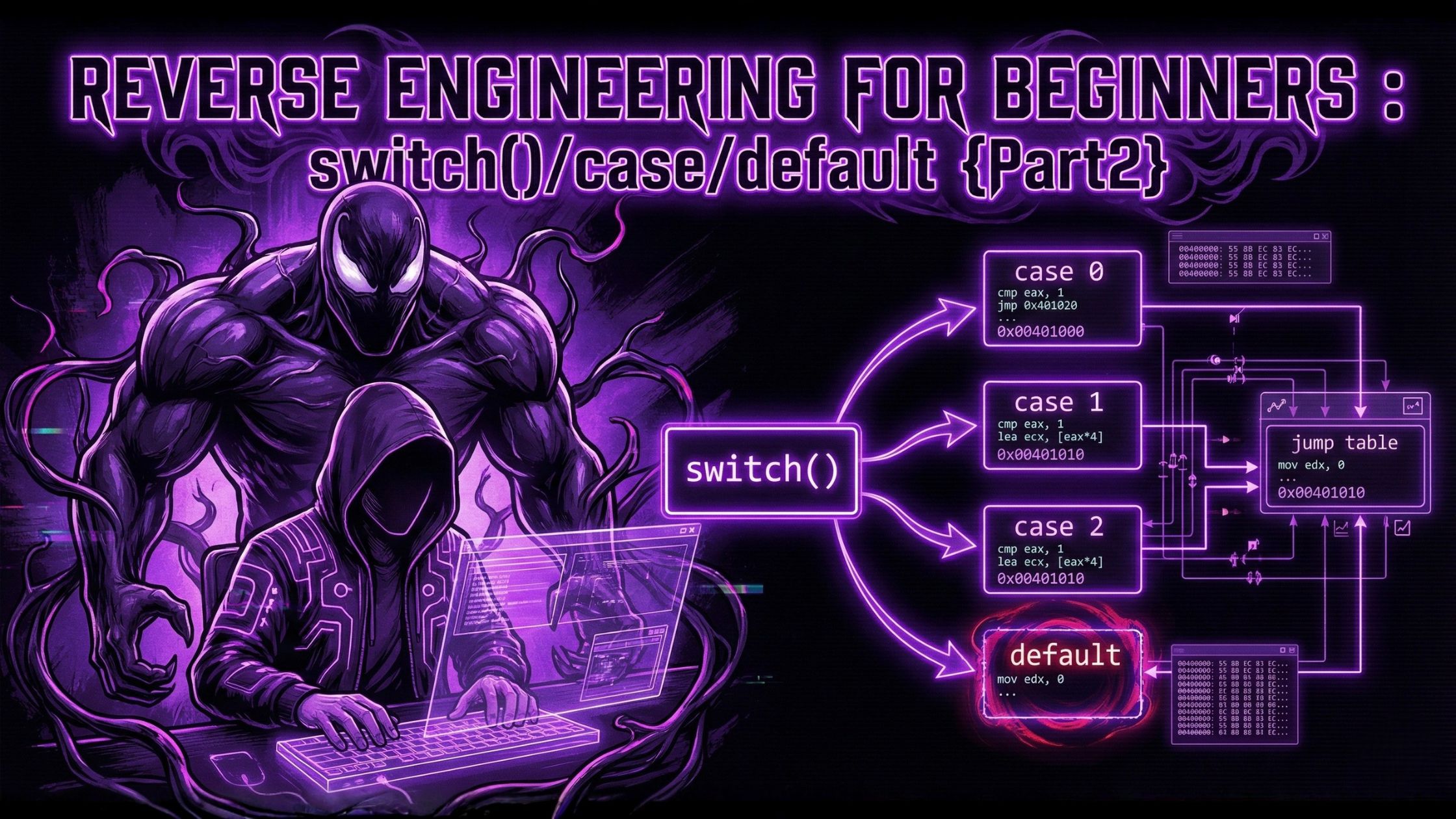

We see two tables here: the first table ($LN10@f) is an index table, and the second ($LN11@f) is an array of pointers to blocks.

First, the input value is used as an index in the index table (line 13).

Here is a brief explanation of the table values:

- 0 is the first case block (for values 1, 2, 7, 10)

- 1 is the second (for values 3, 4, 5)

- 2 is the third (for values 8, 9, 21)

- 3 is the fourth (for value 22)

- 4 is for the default block

Here we get an index for the second table that contains pointers to code and jump there (line 14). It is also noteworthy that there is no case for input value 0. Therefore, we see a DEC instruction at line 10, and the table starts at a = 1, so there is no need to reserve a table element for a = 0. This is a very popular pattern.

Why is this economical? Why not do it like before with just one table of pointers to blocks?

The reason is that the elements of the index table are 8-bit, so all this is smaller and more compact.

GCC

GCC does the same thing in the way we discussed before, using just one table of pointers.

ARM64: Optimizing GCC 4.9.1

No code will be executed if the input value is 0, so GCC tries to make the jump table smaller by starting from input value 1. GCC 4.9.1 for ARM64 uses an even smarter trick.

It is able to encode all offsets as 8-bit bytes. Recall that all ARM64 instructions are 4 bytes in size. GCC exploits that all offsets in this small example are close to each other. Thus the jump table consists of single bytes.

f14:

sub w0, w0, #1 ; input_value -= 1

cmp w0, 21 ; compare with 21

bls .L9 ; branch if less or equal (unsigned)

.L2: ; default case

adrp x0, .LC4

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC4

b puts

.L9:

adrp x1, .L4 ; load jumptable address

add x1, x1, :lo12:.L4

ldrb w0, [x1,w0,uxtw] ; load byte from table (zero-extended)

adr x1, .Lrtx4 ; load address of .Lrtx4 label

add x0, x1, w0, sxtb #2 ; sign-extend byte, shift left by 2 (multiply by 4), add to .Lrtx4

br x0 ; jump to calculated address

.Lrtx4: ; reference point in code section

.section .rodata

.L4:

.byte (.L3 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 1

.byte (.L3 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 2

.byte (.L5 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 3

.byte (.L5 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 4

.byte (.L5 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 5

.byte (.L5 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 6

.byte (.L3 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 7

.byte (.L6 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 8

.byte (.L6 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 9

.byte (.L3 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 10

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 11 (default)

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 12

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 13

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 14

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 15

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 16

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 17

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 18

.byte (.L2 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 19

.byte (.L6 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 20

.byte (.L6 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 21

.byte (.L7 - .Lrtx4) / 4 ; case 22

.text

.L7: ; print "22"

adrp x0, .LC3

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC3

b puts

.L6: ; print "8, 9, 21"

adrp x0, .LC2

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC2

b puts

.L5: ; print "3, 4, 5"

adrp x0, .LC1

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC1

b puts

.L3: ; print "1, 2, 7, 10"

adrp x0, .LC0

add x0, x0, :lo12:.LC0

b puts

.LC0:

.string "1, 2, 7, 10"

.LC1:

.string "3, 4, 5"

.LC2:

.string "8, 9, 21"

.LC3:

.string "22"

.LC4:

.string "default"

The author compiled this example to an object file and opened it in IDA.

This is the jump table:

.rodata:0000000000000064 $d DCB 9 ; case 1

.rodata:0000000000000065 DCB 9 ; case 2

.rodata:0000000000000066 DCB 6 ; case 3

.rodata:0000000000000067 DCB 6 ; case 4

.rodata:0000000000000068 DCB 6 ; case 5

.rodata:0000000000000069 DCB 6 ; case 6

.rodata:000000000000006A DCB 9 ; case 7

.rodata:000000000000006B DCB 3 ; case 8

.rodata:000000000000006C DCB 3 ; case 9

.rodata:000000000000006D DCB 9 ; case 10

.rodata:000000000000006E DCB 0xF7 ; case 11 (default)

.rodata:000000000000006F DCB 0xF7 ; case 12

.rodata:0000000000000070 DCB 0xF7 ; case 13

.rodata:0000000000000071 DCB 0xF7 ; case 14

.rodata:0000000000000072 DCB 0xF7 ; case 15

.rodata:0000000000000073 DCB 0xF7 ; case 16

.rodata:0000000000000074 DCB 0xF7 ; case 17

.rodata:0000000000000075 DCB 0xF7 ; case 18

.rodata:0000000000000076 DCB 0xF7 ; case 19

.rodata:0000000000000077 DCB 3 ; case 20

.rodata:0000000000000078 DCB 3 ; case 21

.rodata:0000000000000079 DCB 0 ; case 22

So for case 1, the value 9 will be multiplied by 4 and added to the address of label Lrtx4. For case 22, the value 0 will be multiplied by 4, resulting in 0. Immediately after label Lrtx4 is label L7, where the code that prints "22" is located.

There is no jump table in the code section; it is placed in a separate read-only data (.rodata) section (there is no special need for it to be in the code section). There are also negative bytes (0xF7), which are used to go back and jump to the code that prints the "default" string (at .L2).

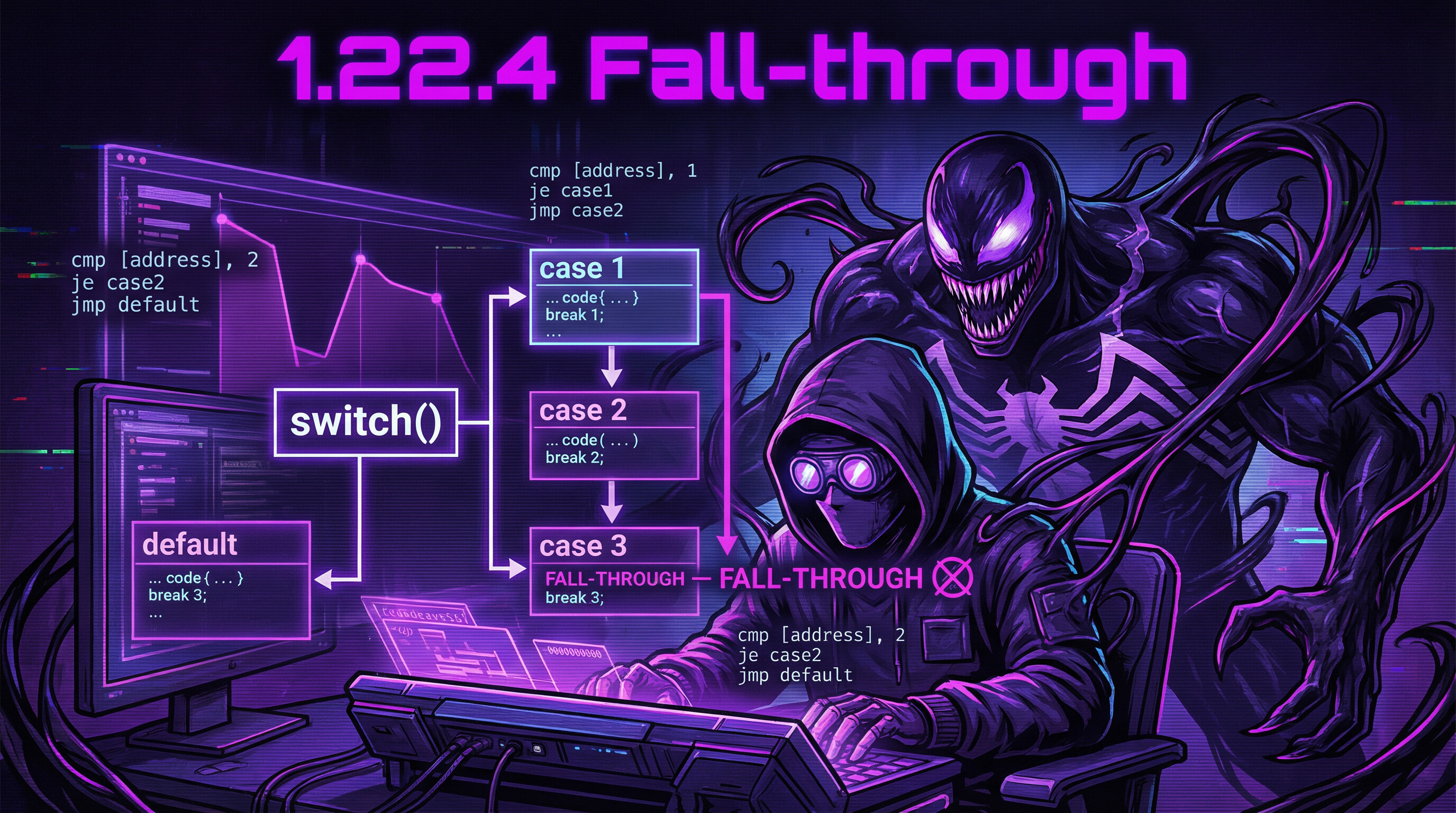

1.22.4 Fall-through

Another popular use of switch() is what is called "fallthrough".

A simple example:

bool is_whitespace(char c) {

switch (c) {

case ' ': // fallthrough

case '\t': // fallthrough

case '\r': // fallthrough

case '\n':

return true;

default: // not whitespace

return false;

}

}

A bit harder, from the Linux kernel:

char nco1, nco2;

void f(int if_freq_khz)

{

switch (if_freq_khz) {

default:

printf("IF=%d KHz is not supportted, 3250 assumed\n", if_freq_khz);

/* fallthrough */

case 3250: /* 3.25Mhz */

nco1 = 0x34;

nco2 = 0x00;

break;

case 3500: /* 3.50Mhz */

nco1 = 0x38;

nco2 = 0x00;

break;

case 4000: /* 4.00Mhz */

nco1 = 0x40;

nco2 = 0x00;

break;

case 5000: /* 5.00Mhz */

nco1 = 0x50;

nco2 = 0x00;

break;

case 5380: /* 5.38Mhz */

nco1 = 0x56;

nco2 = 0x14;

break;

}

};

.LC0:

.string "IF=%d KHz is not supportted, 3250 assumed\n"

f:

sub esp, 12

mov eax, DWORD PTR [esp+16]

cmp eax, 4000

je .L3

jg .L4

cmp eax, 3250

je .L5

cmp eax, 3500

jne .L2

mov BYTE PTR nco1, 56

mov BYTE PTR nco2, 0

add esp, 12

ret

.L4:

cmp eax, 5000

je .L7

cmp eax, 5380

jne .L2

mov BYTE PTR nco1, 86

mov BYTE PTR nco2, 20

add esp, 12

ret

.L2:

sub esp, 8

push eax

push OFFSET FLAT:.LC0

call printf

add esp, 16

.L5:

mov BYTE PTR nco1, 52

mov BYTE PTR nco2, 0

add esp, 12

ret

.L3:

mov BYTE PTR nco1, 64

mov BYTE PTR nco2, 0

add esp, 12

ret

.L7:

mov BYTE PTR nco1, 80

mov BYTE PTR nco2, 0

add esp, 12

ret

We can reach label .L5 if the function input is 3250. But we can also reach this label from the other side: we see that there is no jump between the printf() call and label .L5.

Now we can understand why switch() is sometimes a source of bugs:

One forgotten break turns your switch() into fallthrough, and several blocks will be executed instead of one.