Reverse Engineering for Beginners : More about strings

1.23.1 strlen()

Let us talk about loops again. Very often, the strlen() function is implemented using a while() statement.

If you do not know what strlen() does, it simply walks character by character until it finds a zero (NULL terminator), stops, and returns the number of characters before it.

Here is an example:

Imagine the string as a row of characters in memory:

The last character is always a NULL character:

Back to our topic.

This is what happens in the standard MSVC libraries:

x86: Non-optimizing MSVC

Let us compile:

We encountered two new instructions here: MOVSX and TEST.

The first — MOVSX — takes a byte from a memory address and stores the value in a 32-bit register.

MOVSX means MOV with Sign-Extend.

MOVSX sets the rest of the bits, from bit 8 to bit 31, to 1 if the loaded byte was negative, or to 0 if positive. This is the reason.

By default, the char type is signed in MSVC and GCC.

If we have two values, one of type char and the other of type int (also signed), and the first contains -2 (represented as 0xFE), and we simply copy this byte into int, it will become 0x000000FE, which from the perspective of signed int equals 254, not -2. In signed int, -2 is represented as 0xFFFFFFFE.

So if we need to transfer 0xFE from a variable of type char to a variable of type int, we need to identify its sign and extend it.

This is what MOVSX does. It is hard to say whether the compiler needed to place the char variable in EDX; it could have taken just the 8-bit part of the register (like DL). It is obvious that the register allocator in the compiler works this way.

Then we see TEST EDX, EDX. You can read more about the TEST

Here this instruction simply checks whether the value in EDX equals zero or not.

Non-optimizing GCC

Let us try GCC 4.4.1:

The result is almost the same as in MSVC, but here we see MOVZX instead of MOVSX.

MOVZX means MOV with Zero-Extend.

This instruction copies an 8-bit or 16-bit value into a 32-bit register and sets the rest of the bits to 0.

In fact, this instruction is useful only to replace a pair of instructions like this:

On the other hand, it is obvious that the compiler could generate code like this:

This is almost the same thing, but the upper bits in the EAX register would contain random noise.

The author said this is a flaw in the compiler — it is unable to generate clearer code. Honestly, the compiler is not obligated to generate code understandable to humans at all.

The new instruction for us next is SETNZ.

Here, if AL is not zero, test al, al sets the ZF flag to 0, but SETNZ, if ZF==0 (NZ means not zero), sets AL = 1.

In simple terms, if AL is not zero, jump to loc_80483F0.

The compiler generated somewhat redundant code, but let us not forget that optimizations are turned off.

Optimizing MSVC

Now let us compile all this in MSVC 2012 with optimizations turned on (/Ox):

Now everything is simpler.

No need to say that the compiler can use registers with such efficiency only in small functions with few local variables.

INC/DEC are increment/decrement instructions, meaning in other words: add or subtract 1 from a variable.

Optimizing MSVC + OllyDbg

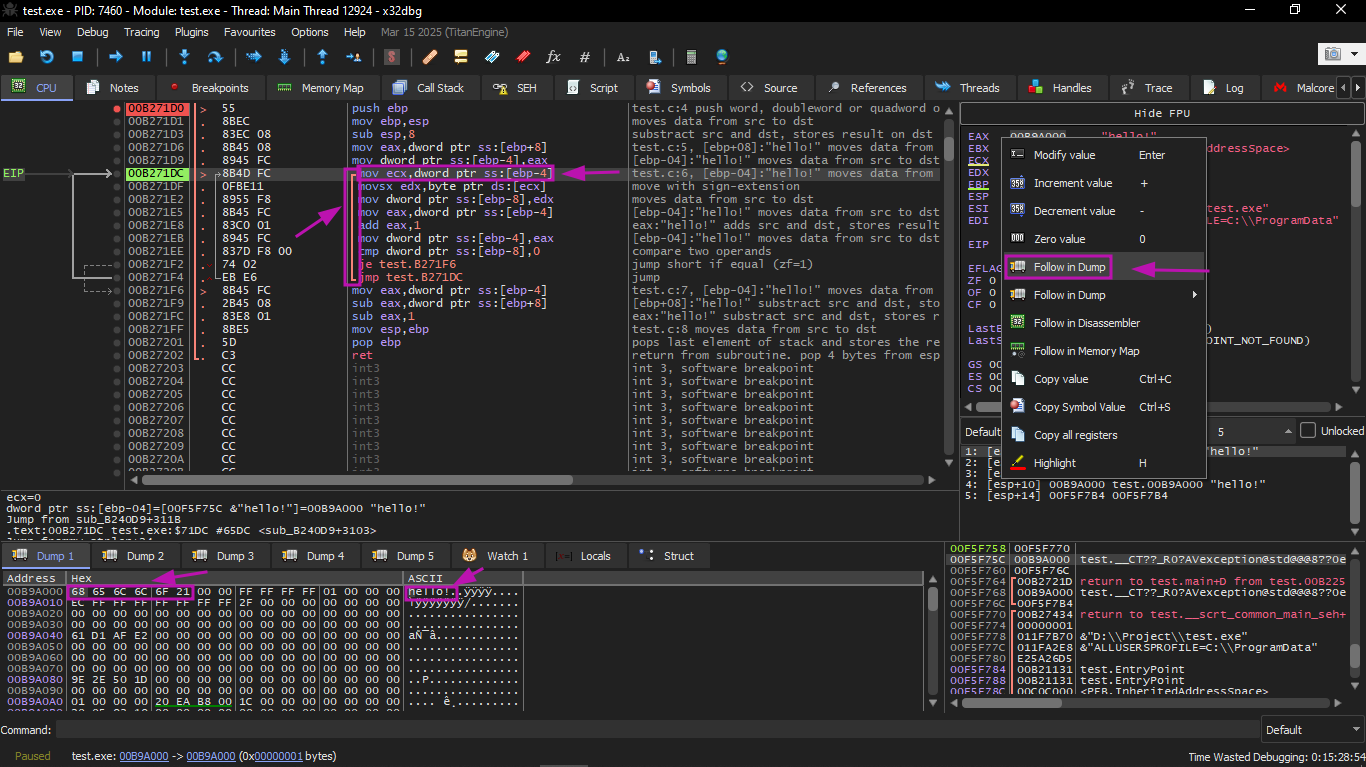

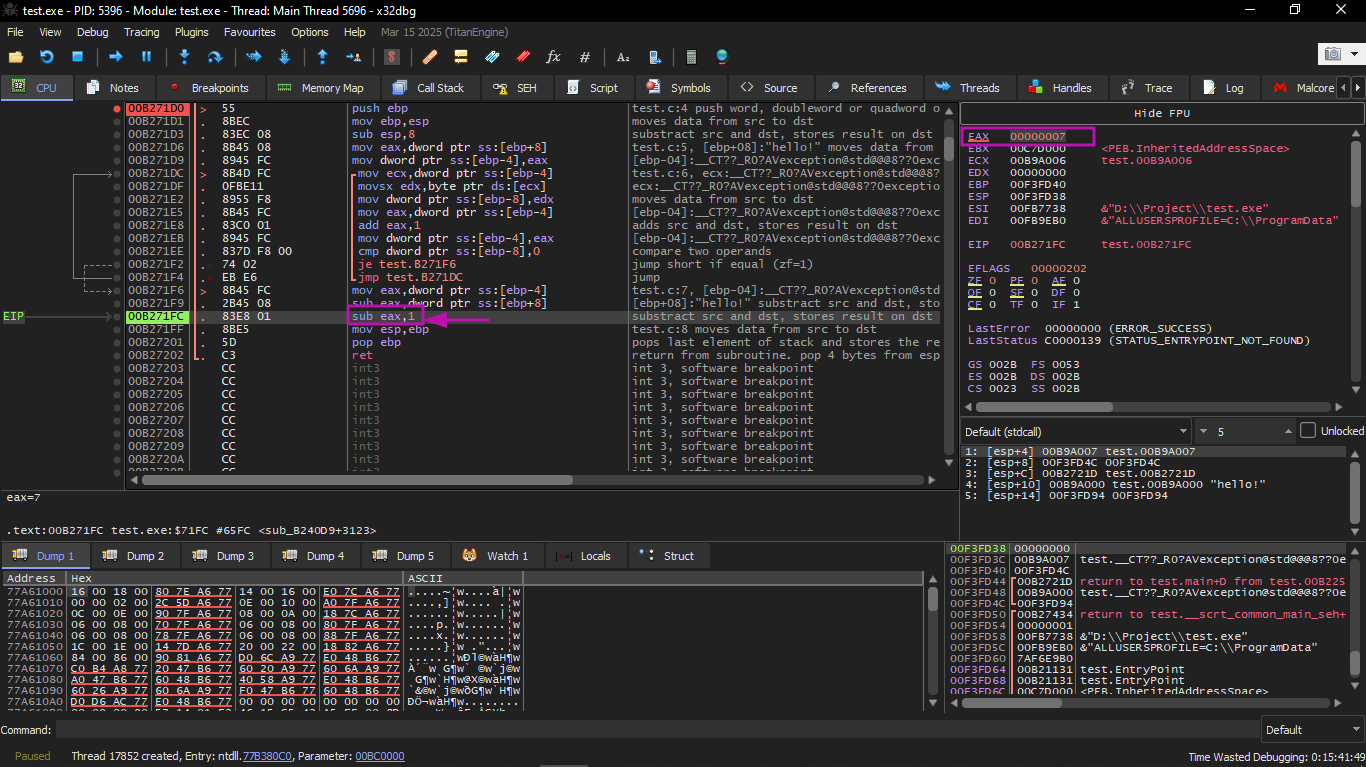

First, we compile the C code, then open the EXE file in x32dbg and go to main.

Here we see that x32dbg detected the loop and for convenience wrapped its instructions in brackets.

If we right-click on EAX, we can choose "Follow in Dump", and the memory window will scroll to the correct place.

Here we can see the "hello!" string in memory. There is at least one zero byte after it, followed by random garbage. If x32dbg sees a register containing a valid address pointing to a string, it displays it as a string.

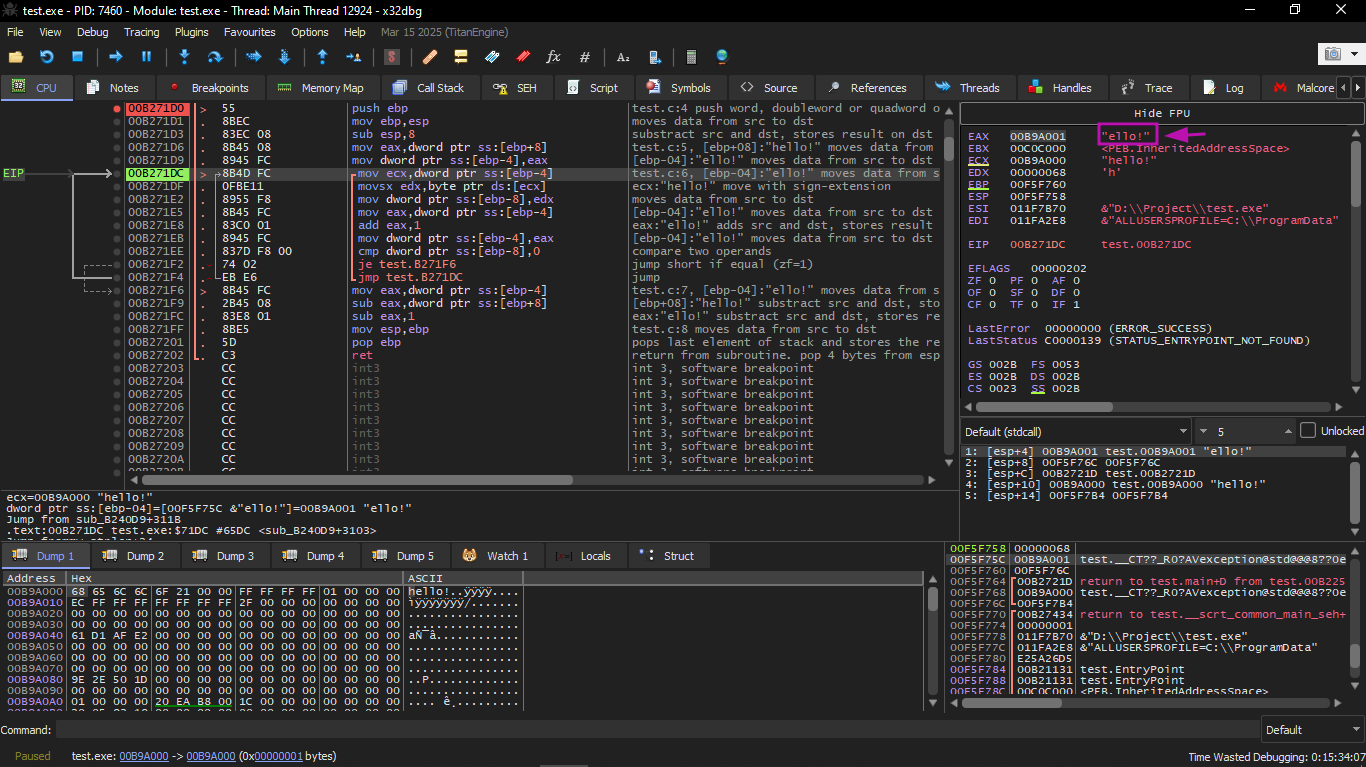

Let us press F8 (step over) a few times until we reach the beginning of the loop body:

We see that EAX contains the address of the second character in the string.

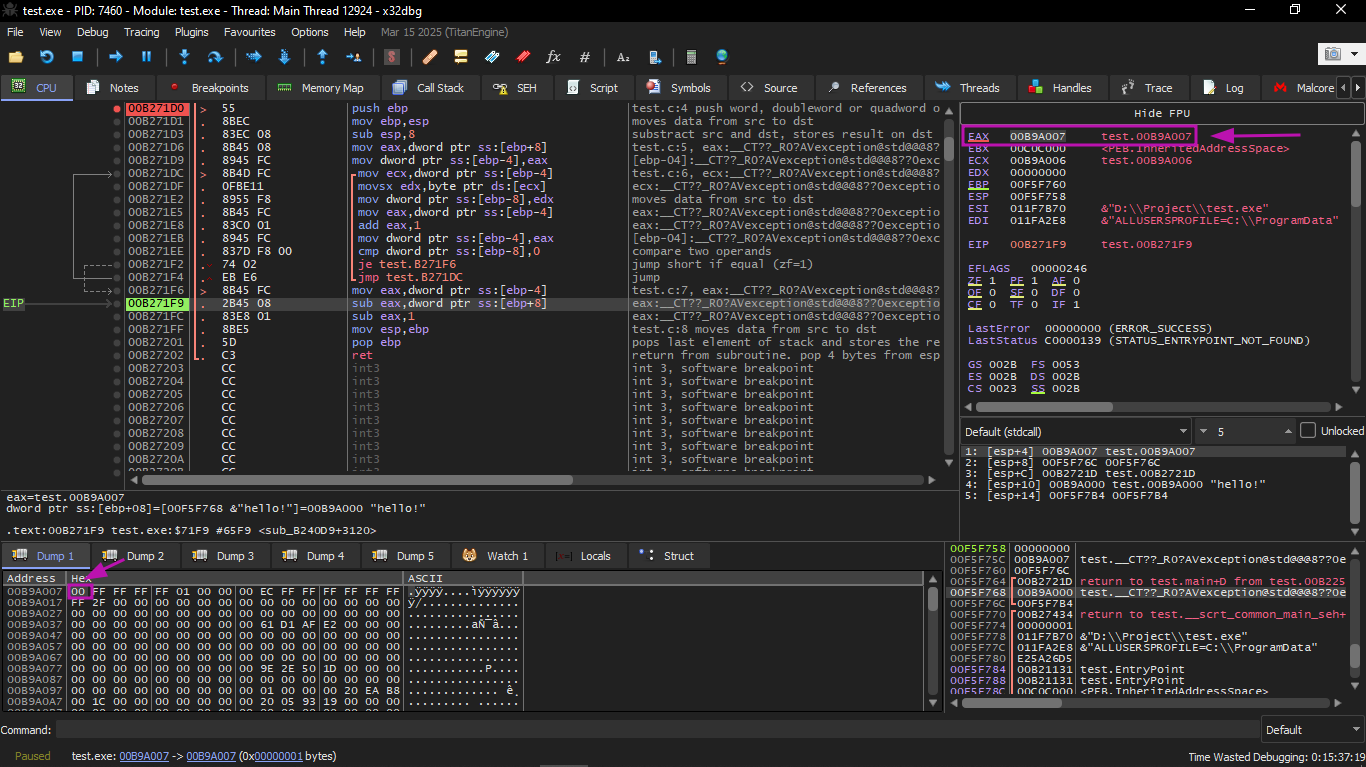

Then we continue pressing F8 a few more times until we exit the loop:

Here we see that EAX now contains the address of the zero byte after the string plus 1 (because INC EAX was executed regardless of whether we exit the loop or not). At the same time, EDX did not change, so it still points to the beginning of the string.

The difference between these addresses is calculated now.

Here the SUB instruction has just been executed:

The difference between the pointers is now in the EAX register — 7. Indeed, the length of the "hello!" string is 6, but with the zero byte it is 7. But strlen() must return the number of non-zero characters in the string.

So a decrement occurs, and then the function returns.

Optimizing GCC

Let us see GCC 4.4.1 with optimizations turned on (-O3):

Here GCC is similar to MSVC, except for the presence of MOVZX.

But here MOVZX could be replaced with:

Perhaps this is simpler for GCC's code generator to remember that the entire 32-bit EDX register is reserved for the char variable, thus ensuring the upper bits have no "noise" at any point.

Next we see a new instruction — NOT. This instruction inverts all bits in the operand.

You could say it is equivalent to the instruction:

The NOT instruction and the following ADD calculate the difference between the pointers and subtract 1, but in a different way.

Initially, ECX containing the str pointer is inverted and 1 is subtracted from it.

In other words, at the very end of the function right after the loop body, these operations are executed:

... which is functionally equivalent to:

The author asked here why GCC decided this would be better?

His answer was that it is hard to guess. But perhaps both are equivalent in terms of efficiency.

ARM: 32-bit ARM

Non-optimizing Xcode 4.6.3 (LLVM) (ARM mode)

Non-optimizing LLVM generates a lot of redundant code, but here we can see how the function works with local variables on the stack.

There are only two local variables in our function: eos and str. In this listing from IDA, we manually renamed var_8 and var_4 to eos and str.

The first instructions simply save the input value in both str and eos.

The loop body starts at label loc_2CB8.

The first 3 instructions in the loop body (LDR, ADD, STR) load the value of eos into R0. Then the value is incremented and stored back in eos on the stack.

The next instruction LDRSB R0, [R0] ("Load Register Signed Byte") loads a byte from memory at the address in R0 and sign-extends it to 32-bit. This is similar to the MOVSX instruction in x86.

The compiler treats this byte as signed because the char type is signed according to the C standard. This was written about before regarding x86.

It must be said that it is impossible to use an 8-bit or 16-bit part of a 32-bit register in ARM separately from the whole register, as is done in x86.

It is obvious that this is because x86 has a huge history of backward compatibility with its ancestors down to 16-bit 8086 and even 8-bit 8080, but ARM was created from scratch as a 32-bit RISC processor.

Therefore, to process individual bytes in ARM, 32-bit registers must still be used.

So LDRSB loads bytes from the string into R0 one by one.

The following CMP and BEQ instructions check whether the loaded byte equals 0 or not.

If not 0, control returns to the beginning of the loop body. If 0, the loop ends.

At the end of the function, the difference between eos and str is calculated, 1 is subtracted from it, and the resulting value is returned via R0.

Note: no registers are saved in this function.

This is because in the ARM calling convention, registers R0-R3 are called "scratch registers", designed for passing arguments, and we are not required to restore their values when the function ends, because the calling function will not use them again. Therefore, we can use them for anything we want.

No other registers were used here, so nothing is saved on the stack.

Therefore, control can return to the calling function with a simple jump (BX) to the address in the LR register.

Optimizing Xcode 4.6.3 (LLVM) (Thumb mode)

As optimizing LLVM concluded, eos and str do not need stack space and can always be in registers.

Before the loop body starts, str is always in R0, and eos in R1.

The instruction LDRB.W R2, [R1],#1 loads a byte from memory at the address in R1 into R2, and sign-extends it to a 32-bit value, but not only that.

The #1 at the end of the instruction means "Post-indexed addressing", meaning 1 will be added to R1 after the byte is loaded.

Then we see CMP and BNE in the loop body, these instructions continue the loop until a 0 is found in the string.

MVNS (inverts all bits, like NOT in x86) and the ADD instruction calculate eos − str − 1.

In fact, these instructions calculate R0 = str + eos, which is functionally equivalent to what was in the source code

It is obvious that LLVM, like GCC, concluded that this code can be shorter (or faster).

Optimizing Keil 6/2013 (ARM mode)

Almost the same as what we saw before, with the difference that the expression str − eos − 1 can be calculated not at the end of the function, but inside the loop body itself.

The suffix -EQ as we remember means that the instruction executes only if the operands in the previous CMP were equal.

Thus, if R0 contains 0, the two SUBEQ instructions execute and the result remains in register R0.

ARM64

Optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

This algorithm we saw before: find zero byte, calculate difference between pointers, subtract 1 from result. Some comments added by the book author.

It is worth noting that our example is slightly wrong:

my_strlen() returns a 32-bit int, but it should return size_t or another 64-bit type.

The reason is that theoretically strlen() can be called on huge memory blocks larger than 4GB, so it must be able to return a 64-bit value on 64-bit platforms.

Due to my mistake, the last SUB instruction operates on the lower 32-bit part of the register, while the previous one operates on the entire 64-bit register (calculating the difference between pointers).

This is my mistake, and it is better to leave it as is as an example of what the code looks like in this case.

Non-optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

This is longer. Variables here are moved back and forth between memory (local stack) a lot.

Same mistake here: the decrement operation is performed on the lower 32-bit part of the register.

MIPS

MIPS has no NOT instruction, but it has NOR which is OR + NOT.

This operation is used a lot in digital electronics.

For example, the Apollo Guidance Computer used in the Apollo program was built using only 5600 NOR gates.

But the NOR element is not very popular in computer programming.

Therefore, the NOT operation is implemented here as: NOR DST, $ZERO, SRC

(Inverting the bits of a signed number is the same as changing its sign and subtracting 1 from the result.)

So what NOT does here is take the value of str and turn it into −str − 1.

The following addition operation prepares the result.