Reverse Engineering for Beginners : Floating-point unit(Part1)

1.25 Floating-point unit

The author started explaining that the FPU is a part inside the main CPU, specialized in dealing with floating point numbers.

In the old days it was called "coprocessor" and it was somewhat separate from the main processor.

1.25.1 IEEE 754

A number in IEEE 754 format consists of:

* a sign

* a fractional part (significand or fraction)

* an exponent

1.25.2 x86

The author said it is important to look into the idea of stack machines or learn the basics of the Forth language before studying the FPU in x86.

An interesting thing is that in the old days (before the 80486 processor) the coprocessor was a separate chip, and was not always installed on the motherboard. It was possible to buy it separately and install it. Starting from the 80486 DX processor, the FPU became integrated inside the CPU itself.

The FWAIT instruction reminds us of this fact — it puts the CPU in a wait state until the FPU finishes its work.

There are also remnants from that era, which is that FPU instructions start with what are called "escape opcodes" (D8..DF), meaning opcodes that used to be sent to a separate coprocessor.

The FPU has a Stack that can hold 8 registers, each one 80-bit.

And these registers are named:

And for simplicity, IDA and OllyDbg display ST(0) by the name:

And this is called in books: Stack Top

1.25.3 ARM, MIPS, x86/x64 SIMD

In ARM and MIPS the FPU is not a Stack. It is a set of registers we can access any one of them directly, just like the GPR exactly. The same idea is present in the SIMD extensions of x86/x64.

1.25.4 C/C++

The C and C++ languages provide at least two floating types:

* float → single precision (32-bit)

* double → double precision (64-bit)

And it is known that:

* single-precision means the number is stored in a single 32-bit word

* double-precision means it is stored in two words (64-bit)

GCC also supports the type:

With extended precision (80-bit), but MSVC does not support it.

The float type takes the same number of bits as int in a 32-bit environment, but the representation of the number is completely different.

1.25.5 Simple example

Let's look at this simple example:

x86

MSVC

Let's compile it in MSVC 2010:

Listing 1.207: MSVC 2010: f()

The FLD instruction takes 8 bytes from the stack and loads the number into register ST(0), and it is automatically converted to the internal 80-bit format (extended precision).

The FDIV instruction divides the value in ST(0) by the number stored at the address:

And that is the number 3.14 stored in IEEE 754 64-bit format. Because assembly does not support writing floating numbers directly, we are seeing the hex representation.

After executing FDIV, ST(0) contains the result of the division.

By the way, there is an instruction called FDIVP that divides ST(1) by ST(0), pops both values from the stack, and puts the result in their place. If you know the Forth language you will quickly understand that this is a Stack Machine.

After that the FLD instruction adds the value of b onto the stack.

As a result:

* ST(0) = b

* ST(1) = result of a/3.14

After that the FMUL instruction multiplies b (which is in ST(0)) by the number stored at:

Which is 4.1. And the result is stored in ST(0).

The last instruction FADDP adds the two values on top of the stack:

* The result is placed in ST(1)

* Then ST(0) is popped

So the final result remains in:

The function must return the result in ST(0) because that is the calling convention in x86 for floating point. And that is why there are no other instructions besides the function epilogue after FADDP.

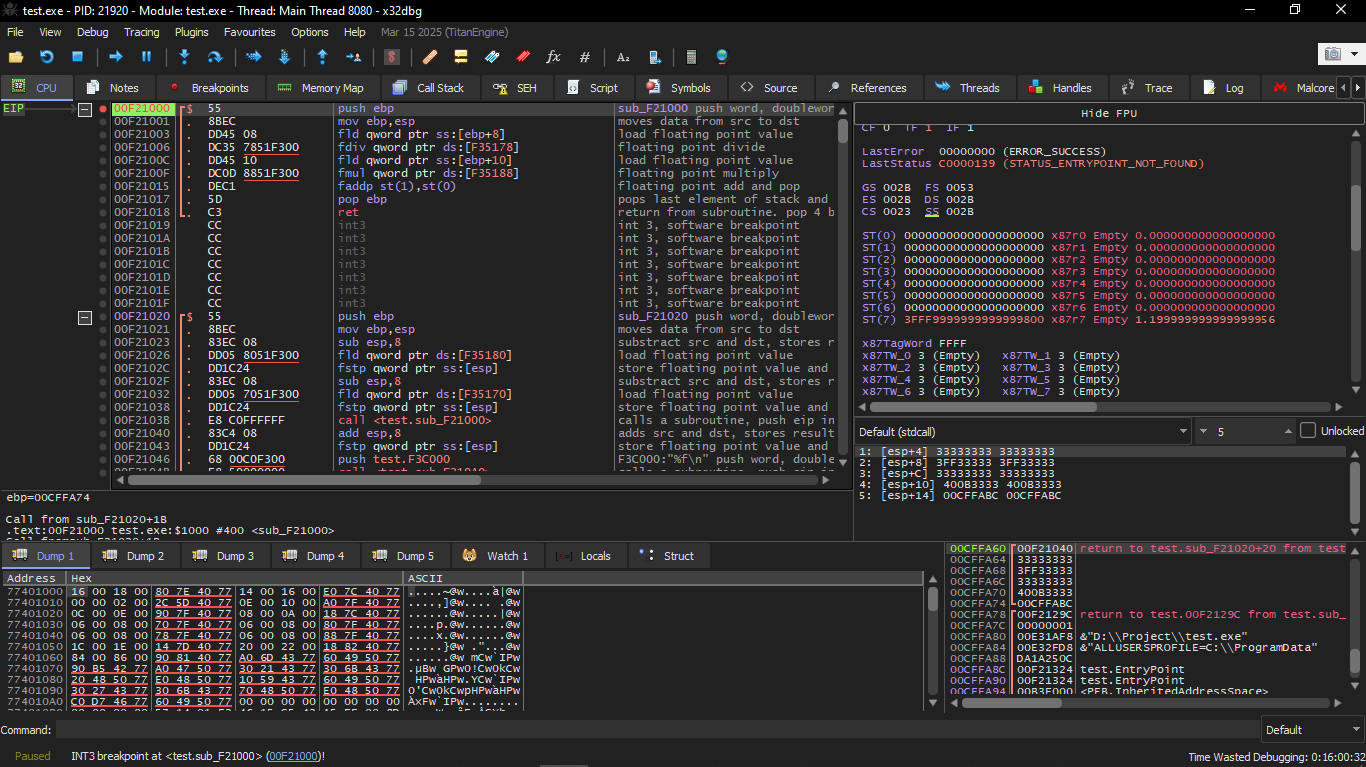

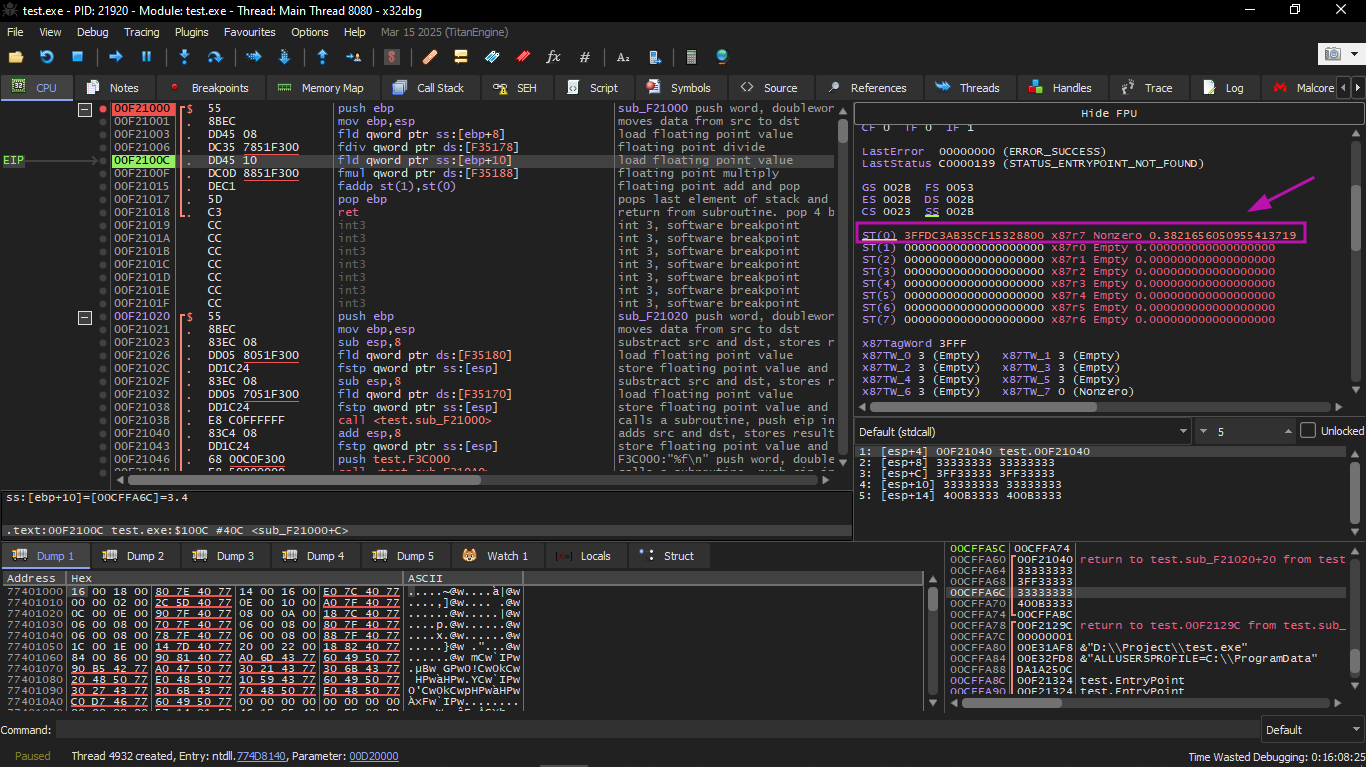

MSVC + OllyDbg

We will do this also on x32dbg and we will compile it this way:

And then we will run the exe on x32dbg.

Two pairs of 32-bit words highlighted in red in the stack. Each pair is a double number in IEEE 754 format, and they were sent from main().

We are seeing how the first FLD instruction loaded the value (1.2) from the stack and placed it in ST(0):

Due to unavoidable conversion errors from 64-bit IEEE 754 to 80-bit (which the FPU uses internally), we are seeing 1.1999… which is close to 1.2.

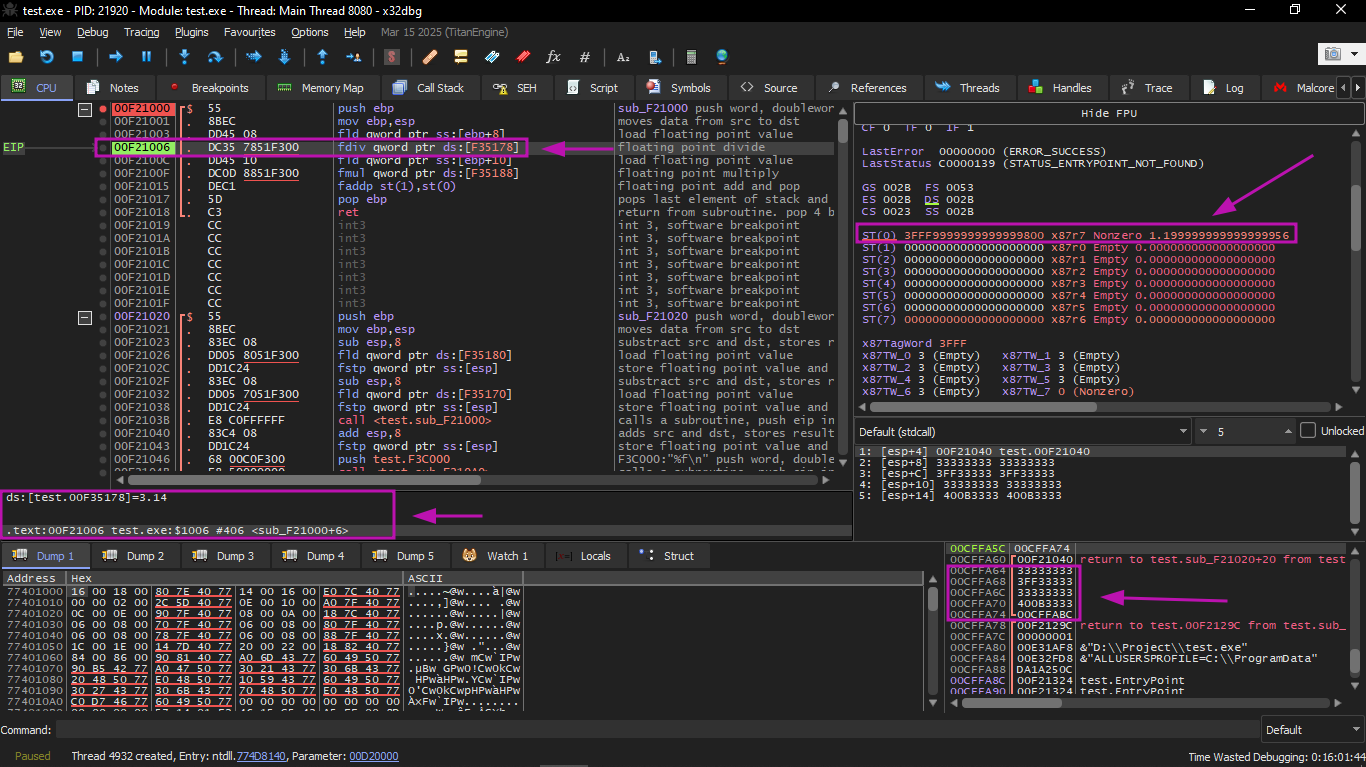

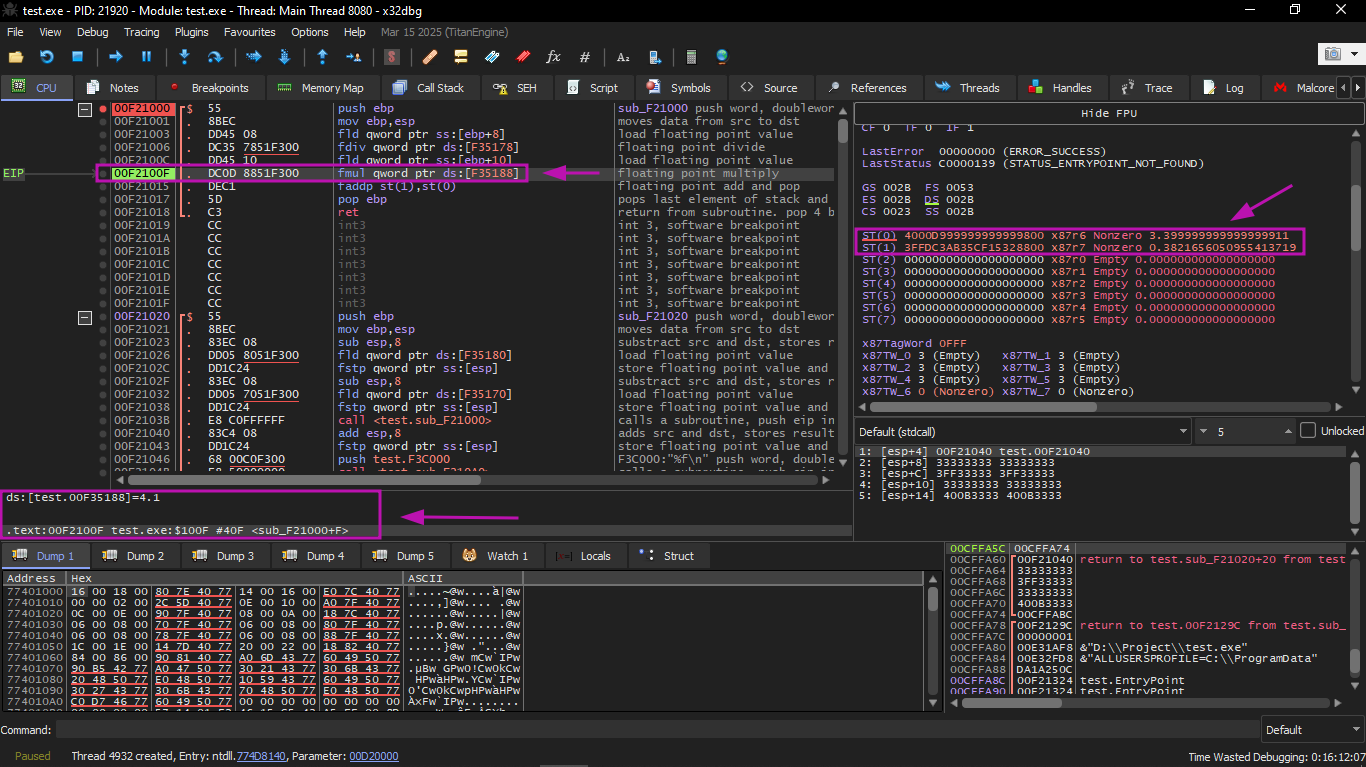

Now EIP is pointing to the next instruction (FDIV), which loads a double (constant) number from memory.

The FDIV instruction was executed, and now ST(0) contains 0.382… (the result of the division):

The next FLD instruction was executed, and loaded 3.4 into ST(0) (here we see the approximate value 3.39999…):

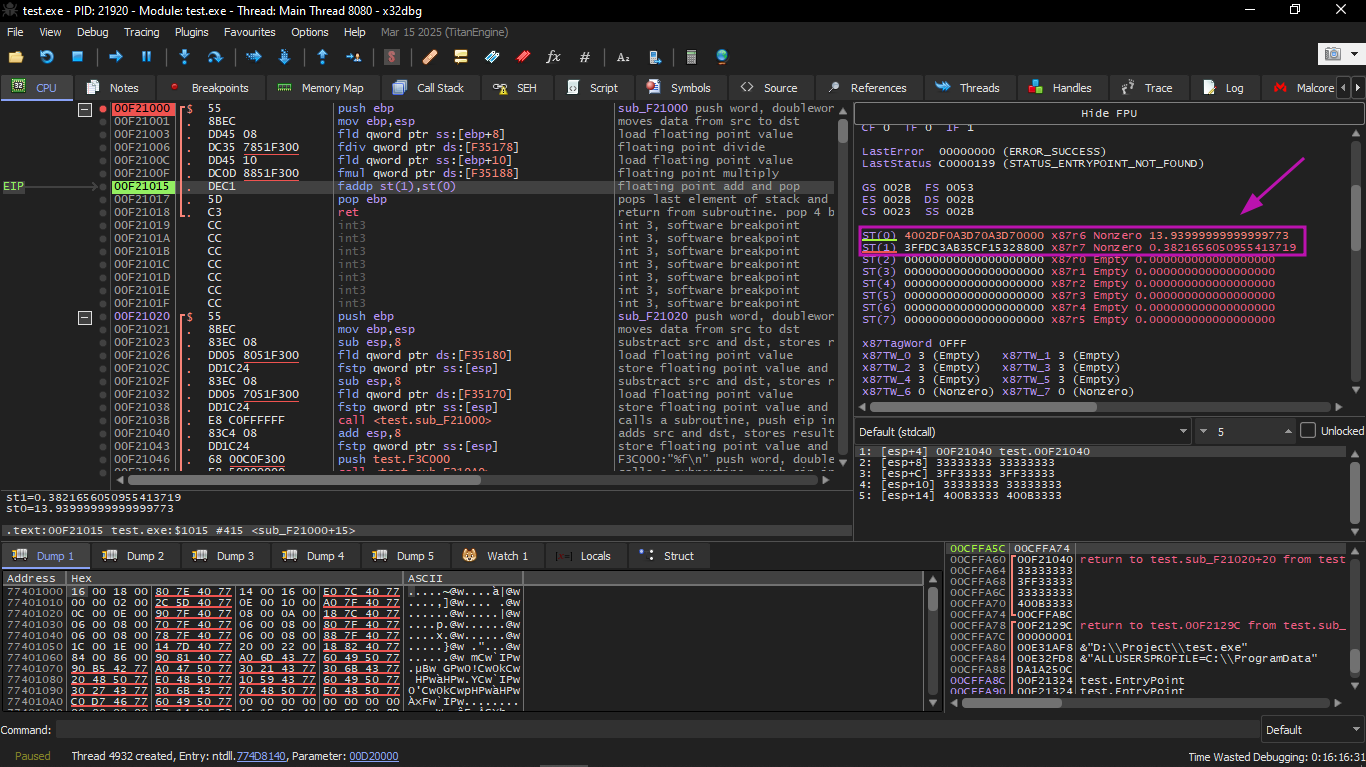

At the same time, the result of the division was pushed into ST(1). Now EIP is pointing to the next instruction: FMUL. It loads the constant 4.1 from memory.

After that: the FMUL instruction was executed, so the result of the multiplication is now in ST(0).

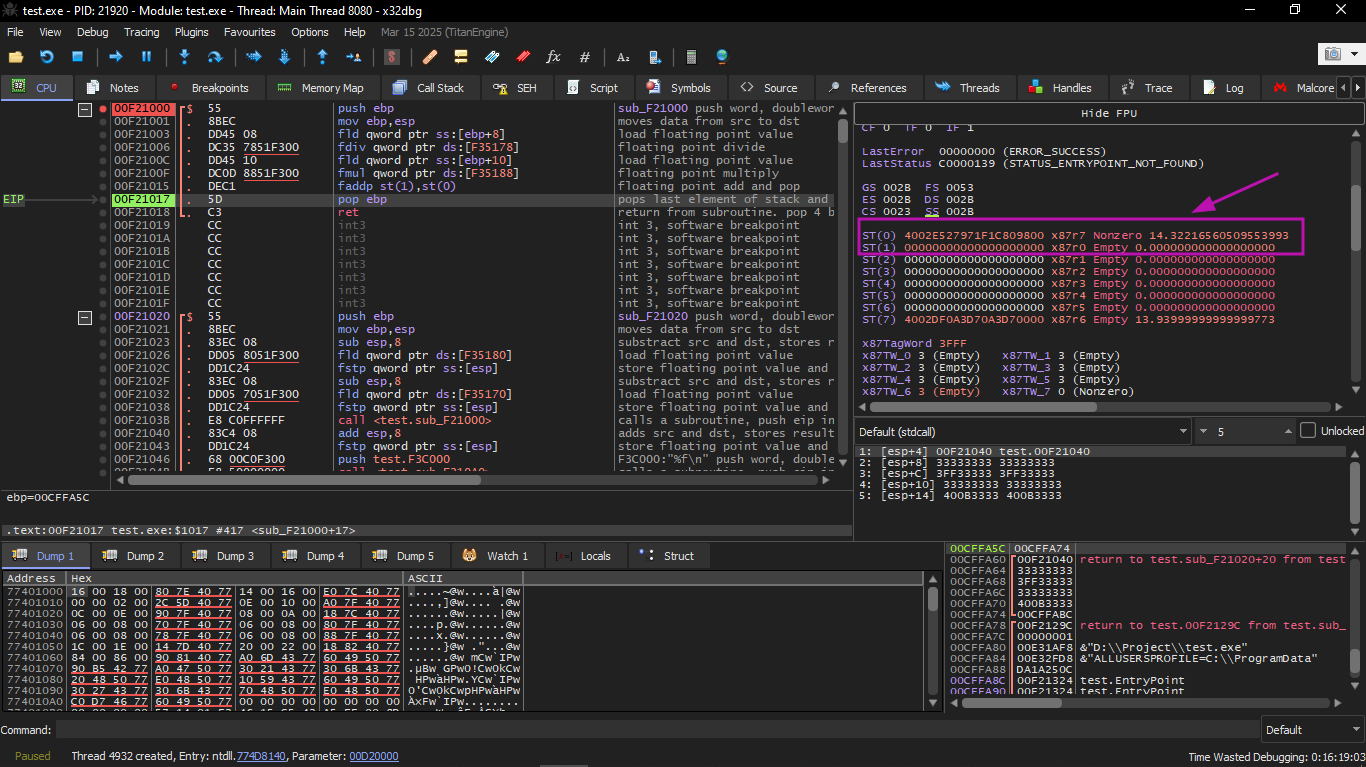

After that: the FADDP instruction was executed, and now the result of the addition is in ST(0) and ST(1) was cleared:

The result remained in ST(0), because the function returns its value in ST(0). main() then takes this value from the register.

We also see something slightly strange: the value 13.93… is now present in ST(7). Why?

As we read earlier in the book, the FPU registers are a Stack. But that is a simplification. Imagine if it were implemented literally in hardware that way, the contents of the 7 registers would have to be moved or copied every time a push or pop happens — and that is a lot of work.

In reality, the FPU has only 8 registers and a pointer called TOP that contains the number of the register which is the current "top of the stack".

When a value is pushed, TOP moves to the next available register, and then the value is written there.

When a pop happens, the operation is done in reverse, but the register that was cleared is not zeroed out (it could be zeroed, but that is extra work and reduces performance).

And that is why this is what we are seeing here.

We could say that FADDP stored the sum in the stack and then popped an element. But in reality, the instruction stored the result and then moved the TOP pointer.

And to be more precise, the FPU registers are a circular buffer.

GCC

GCC 4.4.1 (with the -O3 option) produces almost the same code, but with a small difference:

Listing 1.208: Optimizing GCC 4.4.1

The difference is that first 3.14 is placed on the stack (in ST(0)), and then the value of arg_0 is divided by the value in ST(0). FDIVR means Reverse Divide — meaning it divides with the dividend and divisor swapped.

There is no similar instruction for multiplication, because multiplication is a commutative operation, so we use FMUL normally without an -R version.

FADDP adds the two values and also pops one of them. After this operation, ST(0) contains the sum.

ARM: Optimizing Xcode 4.6.3 (LLVM) (ARM mode)

The author mentioned that before ARM unified its floating point support, many companies used to add their own custom extensions. Then VFP (Vector Floating Point) became standard.

An important difference from x86 is that in ARM there is no stack, you work with registers directly.

Listing 1.209: Optimizing Xcode 4.6.3 (LLVM) (ARM mode)

We are seeing new registers with the letter D. These are 64-bit registers, and there are 32 of them. They can be used for double, and also for SIMD (NEON). There are also 32 S registers (32-bit) for float.

Easy to remember:

* D = Double

* S = Single

The constants 3.14 and 4.1 are stored in memory in IEEE 754 format. VLDR and VMOV are like LDR and MOV but they work on D-registers.

Functions receive arguments in R-registers, but each double is 64-bit, so it needs two registers.

VMOV D17, R0, R1 combines R0 and R1 into 64-bit and places them in D17. And the reverse is true when returning.

VDIV, VMUL, VADD are floating point instructions for division, multiplication and addition.

ARM (Thumb mode – without FPU)

Keil here generated code for a processor that has no FPU or NEON:

Instead of using FPU instructions, it calls library functions that emulate these operations. This is called:

* soft float / armel (emulation)

* hard float / armhf (using a real FPU)

ARM64: Optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

Very concise code:

Listing 1.210

FMADD does:

In a single instruction.

ARM64: Non-optimizing GCC

The code is much longer, with many value transfers between registers and memory, and there are FMOV instructions that are clearly redundant. It is obvious that GCC 4.9 at that time was not yet strong in generating ARM64 code.

An important point: ARM64 registers are 64-bit, so it is possible to store a double directly in a GPR, and this is not possible in a 32-bit CPU.

1.25.6 Passing floating point numbers via arguments

x86

Let's see what came out in (MSVC 2010):

Listing 1.212: MSVC 2010

FLD and FSTP transfer values between the data segment and the FPU stack. pow() takes the two values from the stack and returns the result in ST(0). printf() takes 8 bytes from the local stack and interprets them as a double.

By the way, it was possible to use a pair of MOV instructions instead of FLD/FSTP, because the values in memory are already in IEEE 754 format, and pow() also takes them in the same format, so no conversion is needed.

ARM + Non-optimizing Xcode 4.6.3 (Thumb-2)

As said before, double numbers (64-bit) are passed in pairs of R-registers. _pow takes:

* the first argument in R0 and R1

* the second in R2 and R3

And returns the result in R0 and R1. The result is moved to D16 and then to R1 and R2 so that printf() can take it. The code has some redundancy because optimization is disabled.

ARM + Non-optimizing Keil (ARM mode)

Here there is no use of D-registers, but pairs of R-registers.

ARM64 + Optimizing GCC (Linaro) 4.9

Listing 1.213

The constants are loaded into D0 and D1. pow() takes them from there. The result returns in D0. And it is passed to printf() without any modification, because:

* Integers and pointers are passed in X-registers

* Floating point numbers are passed in D-registers